Mission Matters #58 – Living Commitments: The Student Personnel Point of View

This year we are exploring intellectual traditions associated with UIndy’s schools and colleges. In this month’s issue of Mission Matters, our colleague Joshua Morrison, Director of the Center for Advising and Student Achievement (CASA), reminds us that student success is “everybody’s business.”

Introduction by Michael G. Cartwright, Vice President for University Mission and Associate Professor of Philosophy & Religion

Josh and his colleagues in CASA take seriously that they are not the only UIndy staff employees who engage students. Sunni Manges, Steve Smith, Robin McClarnon and their colleagues carry out their roles in the awareness that their colleagues in the Office of Campus Life, Student Affairs, the Professional Edge Center, and other campus offices also engage students in helpful ways. By definition, this has to be a team effort.

We seldom take the time to think about how this state of affairs has evolved in higher education more generally as well as here on our own campus. In his thoughtful essay, Josh calls attention to one of the charter statements about student development. While The Student Personnel Point of View (1937) identified more than 20 aspects of the “obligation to consider the student as a whole,” the most significant was the final point, which called for ongoing analysis: “Carrying on studies designed to evaluate and improve these functions and services.” To do that in a disciplined way is what the “living commitments” of student personnel entails.

In retrospect, this ongoing mandate entails the kind of institutional reflection and practice that Ernest Boyer dubbed the “scholarship of application” in his classic study Scholarship Reconsidered, produced by the Carnegie Endowment for the Advancement of Teaching (1990). Josh also reminds us that this second classic text informs the work we do today. As Boyer explained, given “the complex social and economic and political problems of our time” the scholarship of application “increasingly requires a team approach” (80). And perhaps nowhere is this more the case than with respect to the institutional obligation to the development of the student as a person.

CASA’s staff are by no means the only UIndy employees who are committed to engage students with full-orbed concern for the many factors that inhibit or advance student achievement. In ongoing ways, UIndy’s student personnel must engage in ongoing reflection about how best to address emergent student needs. That is precisely why these roles have continued to evolve over the past four decades.

As part of the new University structure, in the early 1990s, the professional schools and the College of Arts & Sciences created the office of “the key advisor” to accompany the new general education curriculum. This new role was intended to serve the needs of undergraduate students who were enrolled in particular pre-professional curricula as well as those who had not yet declared a major. Over time, it became clear that not all advising questions could be located within that structure.

In 2013, the Center for Advising and Student Achievement (CASA) was created with a mandate to address obstacles that undergraduate students encountered in the course of making their ways from matriculation to graduation. This more integrative model, which has adopted a team approach, provides for both specialization and generalist pathways. Shortly thereafter, the Professional Edge Center was created. In this latter case, experienced professionals work with students to help them transition from curricular preparation to the world of work and/or graduate and professional educational opportunities.

No doubt, we will make future adjustments in order to keep faith with what Josh aptly describes as our “living commitments” to students. And when we do, the CASA staff and other student personnel will know what changes to make because of what they have learned through the scholarship of application. -MGC

“Living Commitments in Advising and Student Affairs”

by Joshua Morrison, Director of the Center for Advising and Student Achievement

by Joshua Morrison, Director of the Center for Advising and Student Achievement

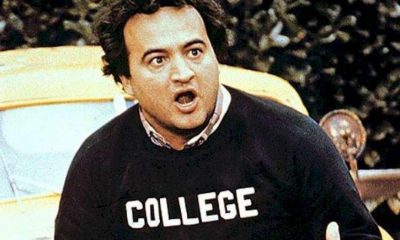

Readers of a certain age may recall the raucous film Animal House, starring among others the late John Belushi, Karen Allen, Tim Matheson, Donald Sutherland, Kevin Bacon, and John Vernon (d. 2005). Vernon, who portrayed Dean Vernon Wormer, gave us a memorable turn as a student affairs leader (in his role, Dean of Students) who was committed to student discipline and orderly behavior at the fictional Faber College*. A sense of propriety prevents me from linking to the film’s relevant clips, but suffice it to say that the movie earns its R (restricted) rating for good reasons.

Animal House was set in 1962, dramatizing the exploits of a band of fraternity brothers engaged in a series of hijinks meant to skirt the college rules while retaining their house charter. Under the watchful eye of Dean Wormer and co-opted college student Greg Marmalard, the brothers of Delta House cheat on exams and throw toga parties, placing them on double-secret probation. Besides the sight gags and crude humor, there are some lessons to be learned in this classic film. The first, a commentary on student academic life, and the second, a deeper exploration of student life outside the classroom.

One key item is a striking absence of the faculty and curriculum, two features of college life students experience throughout their time in higher education. In the famous midterm grades scene, Dean Wormer, with a monologue that would frighten modern Registrars, reports the interim grades of several Delta House members, including the news that each is expelled from Faber College. Only Professor Dave Jennings, played by Donald Sutherland, provides a window into what college students may expect of college faculty. This particular professor is not too interested in excellence in teaching, nor the holistic development of students. Research and creative activity are an afterthought, or simply go unmentioned. Neither Wormer nor Jennings are figures to emulate.

A work that also parodied certain aspects of college life, Animal House takes dramatic and comedic license with the lengths to which colleges and universities might go to restrict student behavior. An extreme example of in loco parentis, Wormer’s actions to dismiss the rowdy Delta brothers from the college were not repeated at Indiana Central. Though “Greek Life” through social fraternities and sororities has been discussed at the University, only for a relatively brief time did the student organizations Lambda Chi and Beta Theta operate at Indiana Central (Hill, 2002, p. 329). During the Animal House years, the two most pressing student social issues were compulsory chapel service (reduced then to just a few days per week) and social dancing. Various student petitions and resolutions had been advanced over the years in support of social dancing, with President Good and faculty leaders, not to mention Evangelical United Brethren members, routinely disfavoring such a practice.

Even so, President Esch, in response to a 1961 student government petition to allow social dancing at the University, responded with a seven-page statement entitled “A Philosophy for Social Life at Indiana Central College.” This, according to University historian Frederick D. Hill, discussed the goals of Christian higher education, the development of programs (and with them, culture) in pursuit of those goals, and the fact that these have been subject to change with circumstances over time (Hill, 2002, p. 325). Ultimately, Esch found no definitive scriptural basis to disallow dancing and revealed to the faculty in the spring of 1961 that social dancing would be coming to Indiana Central. Though social dancing was now acceptable, in 1962 the college renewed efforts to encourage appropriate standards of dress for students. Thus, “blue jeans and athletic T-shirts” were outlawed in classrooms, as well as “Bermuda shorts” in the library, general offices, and in classrooms, among other restrictions (Hill, 2002, p. 326). Clearly, then, Animal House type antics were not common at Indiana Central, though standards, attitudes, and student behaviors were changing.

Animal House type performances may have been rare at Indiana Central. Even so, students in the 1960s and beyond did experience an active social and academic life on campus. Alumni of the University now working on campus in a variety of roles often reflect on their student days, when they were living in an environment that intentionally and meaningfully integrated both in-class and out-of-class life. Student development, meaning the continuous process of growth in experience, knowledge, and discernment of students, occurs in both formal and informal settings. Because of this, student development should be of interest and supported by all members of the university community.

College and University Life: More than Academic

University staff engaged in student development and student affairs roles are vital to ensuring that students can perform to the best of their (developing) ability through the provision of services such as student mentoring, housing and residence life, physical and mental health care, career development, and academic advising. The promise of UIndy to our students is, at least in part, that each student will be treated as an individual, supported in their development, as well as challenged by new ideas, new expectations, and new opportunities.

Indeed, the university’s recent tagline “You Emerge You” speaks to this idea, that the UIndy undergraduate experience is intended to be transformational. You emerge from this special place a new, more capable, confident, self-aware version of yourself. As students graduate high school and transition into a more independent young adulthood, traditional students are equipped with some basis of experience and academic skills. Yet they are unfinished, still malleable, often without a clear sense of direction, purpose, and an intentional, self-directed meaning to their lives. What will they make of it, and who will help them? Just as important, how will this sort of support be provided, and of what kind?

The Emergence of Student Affairs & Student Services

The need for American colleges and universities to address students as individuals has been established since at least 1925 when in January the National Research Council’s Anthropology Division met to discuss current problems in higher education and addressed at this meeting the issue of vocational guidance for college students (American Council on Education, 1937). Out of this meeting and the subsequent American Council on Education’s conference in June 1937 came a founding document of student affairs and student services work, The Student Personnel Point of View. This document reflects concern for the student as a whole person, emphasizing that colleges and universities should set their task to be not just the creation of new knowledge and competent professionals in a variety of occupations, but also the development of the student in a multitude of ways. The list includes 23 items that those in “student personnel” should attend to, including health and safety, housing, food service, orientation, occupational and vocational counseling, family relationships, student records, student discipline, extracurricular activities, and educational planning and job placement (pp. 3-4). Importantly, the 23rd item indicates the need for student services units to evaluate and improve these services over time, suggesting that a regular cycle of development, assessment, planning, and implementation is necessary.

Indeed, The Student Personnel Point of View took seriously the notion of a college or university as a place where a robust, intentional, and systematic co-curriculum was to be in place to supplement the academic curriculum. The statement also explicitly linked the “student personnel” perspective with the academic mission and classroom instruction, business services and administration, K-12 schools, and post-graduate life, including employers. The University of Indianapolis has over time demonstrated its commitment to the co-curriculum and student services. Professor Frederick Hill’s telling of UIndy’s history, Downright Devotion to the Cause, mentions specifically the concern among faculty and staff for student health as early as the 1910s and 1920s (2002, p. 203). This wasn’t the only concern of the University and of its faculty, however.

During Professor Marvin Henricks’ time on the faculty, the expectation of President Esch and others was that students would receive both practical education in the classroom and laboratory, as well as moral education and support. Henricks articulated that an enduring value of higher education at Indiana Central and more generally was for students to find meaning and purpose. More explicitly, the mission of a college or university can be at least partially defined as ensuring that students and graduates find meaning in their experience and come to define the purpose of their lives. It is this discernment of purpose and meaning that brings together both the academic enterprise, valuing knowledge and its applications, with student affairs and services. More than just providing fun and games, or suitable housing options, student affairs, and services have become an essential part of the college experience. Often, they provide the connecting tissue that can serve to integrate learning among disciplines, providing structured ways to engage across differences and practice communication, leadership, and collaboration skills.

The intellectual traditions of each functional area vary, but all tend to relate back to the Student Personnel Point of View, and the bedrock assumptions that each individual is unique, valuable in and of themselves, and is entitled to respect, fair treatment, and care. These commitments undergird student development, the art and practice of “meeting students where they are,” and walking alongside them to greater levels of individual autonomy, responsibility, and ultimately, to interdependence – the realization that each person relies, at least in part, on a network of others for support, and is, in turn, relied upon for that support.

As with Henricks in his student days, undergraduates now occupy their time with paid work, student organizations, external social lives, and other pursuits. It’s often noted that students spend only a limited amount of time in the classroom or lab, with a recent American time-use study indicating about 3.5 hours on average per day. The co-curriculum makes up much of the rest and learning about oneself, others, and the wider world is not restricted to formal academic settings. That same study suggested the average time used in pursuit of leisure and sports was four hours. Working for pay comprised 2.3 hours per day, on average. Though we need not despair at these numbers, being averages they obscure the ends of the distribution, this is a reminder that students have complex lives with competing priorities and needs.

It is incumbent upon members of the university community, then, to recognize and act on current student realities. How the various constituents of our community do this or even consider the variety of student needs and constraints, is often influenced by the roles student personnel play here at UIndy. These roles shape the perspectives and values we bring to the question of how we both understand and act to meet student needs while ensuring they receive top-notch instruction and student services.

Framing Perspectives

How institutions like UIndy offer student activities and student services to supplement the academic experience is a matter of ongoing discussion and planning. One helpful way of considering the perspectives of both faculty and student services staff is recognizing their distinct frames of reference and organizational roles.

Decades ago, Gouldner developed the concept of cosmopolitans and locals to describe social roles in an organization (1957, 1958). These concepts have been applied to faculty in higher education scholarship, with the framework that one’s orientation is based on three variables: loyalty to the organization, commitment to professional skills and values, and one’s reference group. Essentially, Gouldner argues, professionals can be grouped as one of two types based on orientation along these three aspects.

Most faculty at universities, especially research universities, can be considered “cosmopolitans.” Their orientation is to external (rather than internal) reference groups, have high commitment to professional skills and values, but with lower loyalty to their organization. This is because peer groups for faculty are not just at their home institution. They are a broad set of academics, not only in peer institutions and US colleges and universities but around the world. International conferences abound on topics from medical ethics to data science to modern interpretations of Shakespeare. It should go without saying that faculty value professional skills. Many earned doctorates, the most advanced degree in their fields, and are disciplinary experts in one or more subfields. Because their peer group is national, if not international, and faculty are rewarded by the advancement of their disciplinary knowledge (often through advancing research/creative activity and/or teaching), it’s little wonder their loyalty to a home institution may be modest. At any time they might be offered a position in another institution with better perquisites and additional opportunities to advance their careers.

In contrast, most staff members are often considered “locals.” They have an internal orientation, focusing their efforts on understanding, operating in, and improving, their organization. Because of this internal orientation, they are more loyal to the organization and see themselves as playing important institutional roles in perpetuating and advancing its interests. Lastly, they are less committed to a specialized set of professional skills. This is not to say that locals aren’t skillful; rather, these professionals are expected to have a variety of skills to meet a broader set of tasks.

This cosmopolitan vs. local idea has been taught in organizational theory courses for decades and has applications to the intellectual traditions among student affairs and student services staff here at UIndy. You may know one or more long-serving staff members at UIndy who seemingly knows everyone on campus and across the years has seen it all. Often, these persons can find the most effective, efficient, and even charitable ways to operate. These are the folks who know the right levers to push, the right call to make at the right time, or how to engage a contentious topic in a manner that brings more light than heat.

There is an intellectual tradition at work here, and it’s not just a fancy term for “playing the game,” or playing it better than others. It’s organizational intelligence at work and in service of the mission, values, and goals of the university. Those who are engaged in the local arena with the best interests of the institution in mind are, in a sense, acting as stewards, who see to it that the foundational commitments and values of the organization are not only understood but lived. The following example illustrates this point.

Recently, an undergraduate student from out of state made her way to the Center for Advising and Student Achievement (CASA). Enrolled in her first semester at UIndy this fall, the student had experienced a myriad of issues, many beyond her control, from the first day of class in August. Roommate concerns, academic adjustment, finding a group of friends, and other personal concerns meant she was at risk of not only poor academic performance but departure from the university even before the semester ended. Referred to CASA, the student arrived to share her story. Her advisor listened carefully and asked follow up questions, identifying the significant issues at hand and developing some potential, imaginative solutions. The student needed some immediate financial support, but even more than that, she needed an individual on campus, a person, with whom to connect and to navigate what can be a complex and confusing organizational bureaucracy.

Through this quite long conversation, the student’s perspective shifted from one focused on deficits and challenges to one of opportunities and engagement. She found that her experiences were not uncommon, and in fact, quite normal for beginning students. Homesickness, an early lack of connection, and her personal concerns all bundled together to create significant barriers to her engagement on campus and in the classroom. Even so, the advisor, in this case, listened intently, interpreted the university experience of this student, and then translated that interpretation into a series of opportunities and options the student could access. No decisions were made on behalf of the student, and no preconceived outcome was achieved. And yet, the student has been guided by a caring member of the university community into greater levels of engagement with UIndy, commitment to her education, and has a much higher likelihood of not only staying at UIndy this fall but returning next year as well.

This situation can be understood as an example of praxis, a term familiar to many in educational studies and related fields. Praxis may be put simply as wisdom grounded in experience, informed by relevant theory. Student Affairs, as an academic field, often seeks to develop reflective practitioners. Reflective practice in student affairs and student services means we intentionally develop, assess, and improve what we do for and with students by integrating our experiences with our disciplinary theory and research backing. In this way, we can contextualize the research findings and make wise decisions about not only what we do, but also how we do it.

To put this into terms familiar to academic colleagues, this advisor could be viewed as engaged in the scholarship of application. Popularized by Ernest Boyer, scholarship of application is one of four main types that may be pursued by college and university faculty (1990). Academic advisors, along with others engaged in student affairs/student services, often rely on robust research findings that help guide practice. Two examples of research findings that inform practice in student affairs and student services can be found here.

In the above situation, the advisor was able to relate to the student’s story and personal concerns, demonstrating that a representative of the institution cared and was committed to engaging with her not only in this moment of crisis but over the longer-term. The student, now having a link on campus and stronger social integration, is more likely to persist, as the improved social integration can benefit her commitment to her education and to the university as a whole. The student now has an ally and contact for future concerns. Even if a CASA advisor can’t solve every issue, we can provide that connection and warm handoff so the student’s needs are met in a timely and effective way.

Living Commitments

Many of us can remember with some clarity our graduation day. Donning the academic robes, mortarboard, feeling the flutter of the tassel in our faces at the most inopportune moments. Whether it was from high school, college, or the culmination of graduate school experience, commencement is a time of celebration, relief, and hope.

Assisting undergraduates in their journeys from an entering first-year or transfer student in a number of ways, student affairs, and student services personnel often work, in unsung and not well-understood ways, to keep students moving toward that graduation stage, where they beam with pride at a challenging thing, done well.

Academic advisors, career coaches, student activities directors, and many others on campus, all contribute to the student’s overall experience at UIndy. We get to be involved with students each day, making connections and helping students make meaning of their college experience. Each student crossing the stage with their diploma cover in hand is a success story for those who contributed, in some small way, to this achievement.

Perhaps it’s time to make a statement, somewhat bold but I think not without support: Student success is everyone’s business. From the facilities staff keeping our classrooms and labs in good working order, to business officers ensuring prompt payment and receipt of funds, to academic advisors encouraging student engagement in their studies, to faculty connecting students to the big ideas and challenges in their disciplines, to Deans and Department Chairs advocating for excellence in research and creative activity — each of us has a role in impacting the lives of every student.

In this sense, everyone is in the “student affairs” business, since our work involves and impacts the lives and experiences of students. Each of us reading these words can live the commitments that colleagues in student affairs and student services strive to uphold: that every student has value, that every student can grow, and that every student is deserving of a place and a voice in this place we call the University of Indianapolis.

* Please note: The word Faber, from the Latin Homo faber, translates as “man the maker.” One wonders if the writers of Animal House (Harold Ramis, Douglas Kenney (d. 1980), and Chris Miller) were aware of this fact.

References

American Council on Education. (1937). The student personnel point of view. Washington, DC: H.E. Hawkes, Ed. Retrieved from http://www.myacpa.org/sites/default/files/studentpersonnel-point-of-view-1937.pdf

Boyer, E. L. (1990). Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities of the professoriate. New York, NY: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching with Jossey-Bass.

Gouldner, A. W. (1957, December 1). Cosmopolitans and locals: Toward an analysis of latent social roles — I. Administrative Science Quarterly, 2(3), 281-306. doi: 10.2307/2391000

Gouldner, A. W. (1958, March 1). Cosmopolitans and locals: Toward an analysis of latent social roles — II. Administrative Science Quarterly, 2(4), 444-480. doi: 10.2307/2390795

Hill, F. D. (2002). Downright devotion to the cause: a history of the University of Indianapolis & its legacy of service. Indianapolis, IN: University of Indianapolis Press.