Poverty Simulation provides eye-opening perspective for students

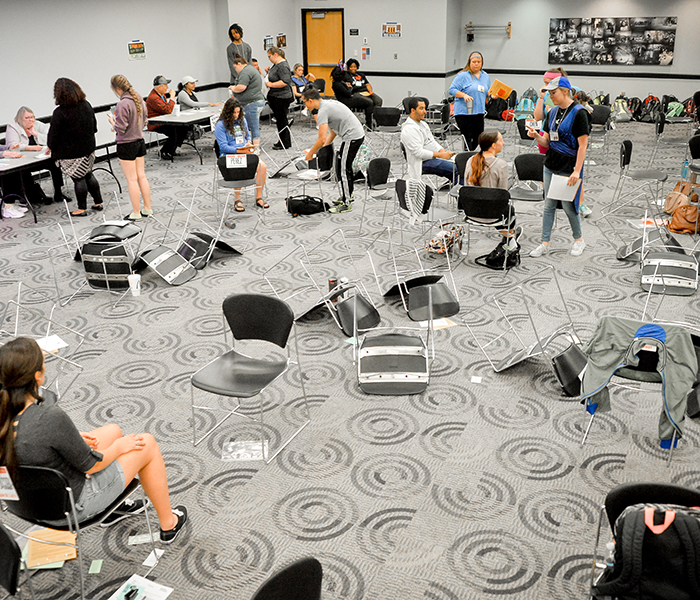

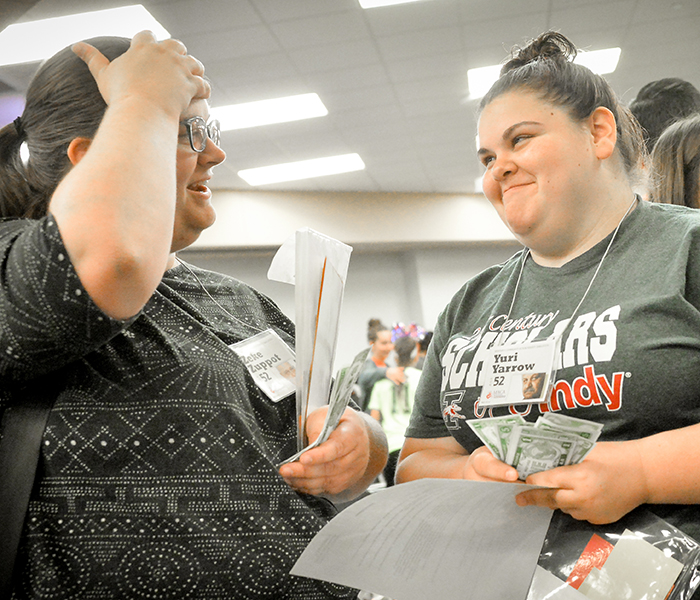

Students from a variety of health disciplines learned firsthand recently the challenges faced by low-income families in a Poverty Simulation held on the University of Indianapolis campus.

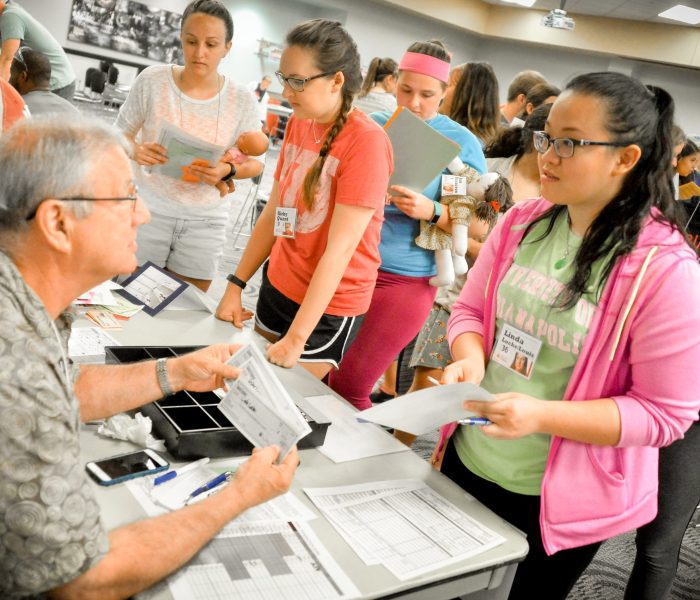

The Poverty Simulation, organized by Anne Mejia-Downs, associate professor, and Julie Gahimer, professor, Krannert School of Physical Therapy, serves as an introductory activity to the Doctorate of Physical Therapy (DPT) Service Learning Course. DPT students were joined by PT assistant, nursing and public health graduate and undergraduate students for the event.

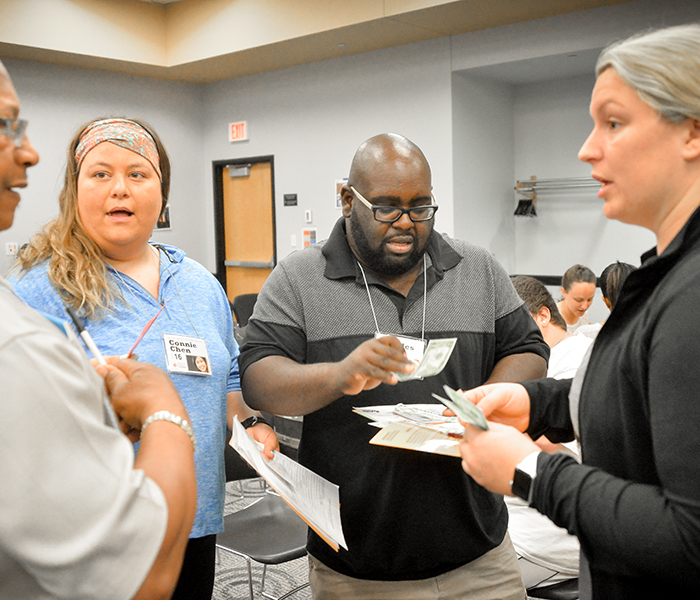

Nearly 100 students, faculty and volunteers played the roles of families navigating welfare, schools, housing and health care systems while sticking to a restricted budget ($65 a day/$24,000 annually or less for a family of four). For the students, the simulation was a small glimpse of what some of their potential clients may face as they try to survive month to month. Some 43 million Americans live in poverty, according to a 2015 U.S. Census report.

“The objective of the simulation is to expose and sensitize participants to the realities faced by low-income families,” said Mejia-Downs. After the simulation, students learned about the work that is being done to address poverty in the greater Indianapolis area and how they can help through service learning opportunities.

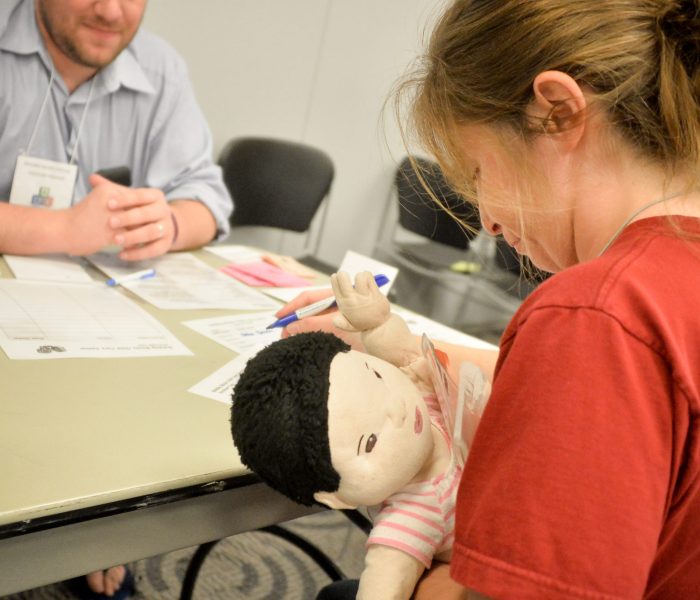

Circles Indy, a local group that works toward poverty solutions, facilitated the simulation, which included interactions with service providers such as schools, banking and federal housing. Students were presented with realistic dilemmas, such as arranging child care during spring break while juggling work responsibilities.

The Poverty Simulation is part of a broad University initiative to address the social and economic issues surrounding poverty in the Indianapolis community. The Gene and Mary Ann Zink Poverty Institute, established in 2015, addresses poverty issues in the community by creating research and experiential learning opportunities for students through scholarships and faculty-guided research. The University’s partnership with Community Health Network also is designed to connect low-income and underserved residents in the area with new health care resources and opportunities. These initiatives position the University to provide solutions and strategies to impact social issues, both locally and abroad.

Learning to see from a new perspective was an important goal of the Poverty Simulation. Some participants wore visors over their eyes to represent a person living with ADHD or gloves to indicate diabetic neuropathy. Each “family” had its own challenges – including eviction by the mortgage company when they failed to pay the rent.

Marie Wiese, executive director of Circles Indy, sees a range of emotions among the role-playing students, including frustration, anger, despair and hopelessness. That’s exactly the point, she said.

“Most participants have a real ‘a-ha!’ moment about what poverty is like. That is especially true when it comes to those playing the roles of children in poverty. They will sometimes do things to help the family that would be totally unthinkable in the middle-class world,” said Wiese.

Grace Connell, a first-year physical therapy student who participated in the simulation, said what surprised her the most were the risks people were willing to take to make ends meet.

“Some were stealing. Others who were college and high-school-aged felt they could not go to school because they needed to work to make money for their family. There was no extra money for when life’s emergencies happened, so we would have to cut into that week’s grocery budget, for example,” Connell explained.

Participants learned that poverty can take many forms. Jamie Wallace, another first-year physical therapy student, was surprised at the economic range of poverty levels.

“I was expecting to have many people who were homeless, but my group actually had a three-bedroom house. However, we were living paycheck to paycheck,” Wallace said.

The goal, Wiese said, is to raise the “poverty IQ” of participants so they can bring that knowledge base with them as they enter the medical field. Instead of assuming that a patient is irresponsible for missing an appointment, Wiese said the Poverty Simulation shows students there are many factors to consider – a broken-down vehicle, running out of phone minutes or lack of child care.

“Helping our medical providers to understand is half the battle. We hope to help the students learn to ask better questions,” Wiese said.

That message resonated with Connell and Wallace.

“I am much more empathetic towards my future patients who I may suspect to be living in poverty. I hope to be respectful of their time as well as their available resources and do everything in my power to give them the high quality health care everyone deserves regardless of socioeconomic status,” Connell said.

Wallace added, “This could be a really good time to get to know what our patients are really going through and if we can help take just one thing off their load for the week.”

Written by Sara Galer, Senior Communications Specialist, University of Indianapolis. Contact newsdesk@UIndy.edu with your campus news.