Mission Matters #64 – Prudent Leadership on Campus Part I: A Hundred Years Ago at ICU

By Michael G. Cartwright, Vice President for University Mission and Associate Professor of Philosophy & Religion

This year we are exploring marks of excellence that can be discerned in the past and present of our institution. Virtues are displayed in the context of practices and social relationships, they reflect moral traditions, they are embodied by exemplars, and they are sustained by institutions such as universities. In MM #63, the focus was on the virtue of collegiality. This week, we are talking about the leadership virtue of prudence, known in some quarters as “the mother of all cardinal virtues.”

The best leaders display multiple marks of excellence, but when you pause to think carefully about the matter, it is hard to disagree with the philosopher’s quip: “whatever is good, must first be prudent.” Even so, some of us rub our chins in doubt. In response, philosophers patiently say: “The key is to avoid being overly abstract by keeping the focus on practical matters – things that result in actions taken not hypotheticals.”

Prudence is not about what leaders might do in ideal circumstances; rather it is about how leaders deal with real-world conditions. This is also why virtue theorists have said that prudence is “the mother” of the other three cardinal virtues (justice, fortitude, and temperance). In all cases, the actions leaders take – seeking justice, displaying fortitude, and acting with temperate restraint — must be reasonably prudent.

“What does this have to do with UIndy?” you may ask. In this month’s Mission Matters essay, I want to call attention to a couple of moments from our university’s history to illustrate prudence as a virtue of leadership. The first is from the period of the founder, culminating in actions taken by the Board of Trustees 100 years ago. (In Part Two, my focus will be on the past eight years, including our battle with the coronavirus.)

Let me begin by reminding you of a couple of basic observations about what leadership virtues and vices are. According to the ancient philosopher Aristotle, virtues exist in a dynamic relationship with excesses and deficiencies. So a person who is virtuous in matters of engaging danger is someone whose action approximates the “the golden mean” between the extremes of cowardice (too much fear) and recklessness (too little fear). A courageous person is NOT someone who is fearless, but rather a person of courage displays the right amount of fear for the right reasons in the right ways while engaging challenging circumstances. A similar pattern of thinking illustrates how leaders enact prudence. A person who lacks prudence is prone to act without due consideration for risk, and a person who is too cautious fails to be prudential.

No one is born with a prudential habit of mind already infused (contrary to what stories of moral heroes might imply). Some persons are quicker studies in prudential matters than others, but many of us learn prudence by trial and error. (I survived my 17th year of life, but it was because I was a very lucky fellow, not because I displayed prudence.) Whether we develop such sensibility quickly or only after making more than our share of mistakes, prudence is a virtue that leaders can ill afford to ignore, especially during a pandemic! Obviously, all of this has impact on the institution’s moral leaders serve. Consider what was happening at Indiana Central University a hundred years ago.

Prudence at Indiana Central University: 1902-1920

There was no great mystery about why Indiana Central University floundered in its earliest years. Beginning with the creation of Otterbein College in Ohio (1847), those adventurous souls who dared to found United Brethren colleges frequently failed to make adequate provision to fund faculty salaries, supplement student tuition, and support college operations even where they had been able to obtain land for a campus and build facilities where faculty and students could carry out the project of higher education. Writing in 1954, one writer summarized the first century of Evangelical United Brethren higher education this way: “The church’s way . . . was strewn with the debris of more than sixty institutions.” The word debris, used in the previous sentence, was not simply metaphorical; the most frequent reported reason why institutions closed was that buildings burned, which is what happened to Hartsville College in 1898.

Knowing why something doesn’t work is only part of the problem. You have to have the means to address the problem in order to act with prudence. At the turn of the twentieth century, the founders of Indiana Central were determined to avoid this pattern of improvident leadership. Bishop Ezekiel B. Kephart, who more than anyone else in the second generation of UB Church was an institutional architect for higher education in the United Brethren Church, had volunteered to spend his first full year of retirement (1906) raising at least $25,000 for the initial endowment for this venture. In 1902, John T. Roberts and William Karstedt worked out a business arrangement that would yield a building debt-free in return for the sale of 446 lots, and this intrepid pair crisscrossed the state of Indiana and continuous states to rally support for this new institution which would be built at a time that several other institutions either had already failed or, like Westfield College in Illinois were on the verge of failing.

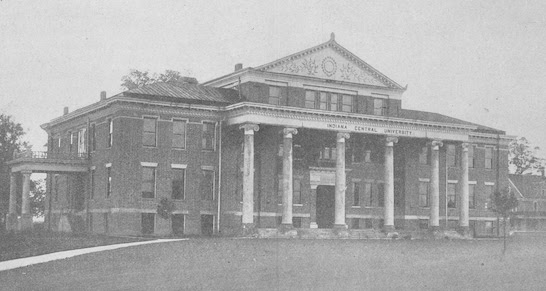

After a promising start, Roberts & company ran into more intractable problems in early 1905. First, the Board of Trustees, which acted on behalf of the United Brethren in Christ Church (the legal owner of the college at that time), simply could not find the kind of experienced executive leadership that they needed. So when they found themselves with a newly completed academic building and all but 100 lots sold, they told the chair of the search committee (J.T. Roberts) that he would have to be the college’s president and that classes would begin in fewer than 100 days. Roberts found enough students and faculty to get started, but when they took that famous photograph of the group standing on the steps of the Portico on Sept. 27, 1905, there were virtually no furnishings in the three-story building and no money for operations.

Second, try as they might, during those first three years President John T. Roberts, et al. could not raise enough money to sustain the institution. The first blow occurred in January 1906 when Bishop Kephart died after only nine days in Indiana. Thereafter, poor J. T. Roberts could only raise $6,000 of the $15,000 goal to endow religious life programming for Kephart Memorial Chapel. By the end of Roberts’ three-year tenure as President, ICU already had accrued a significant debt. For the greater part of the 1908-1909 academic year, a small group of faculty and trustees held things together while a couple of trustees worked with the United Brethren Church’s Board of Education to locate someone who had academic credentials and administrative experience to lead Indiana Central into a brighter future. The person they recruited was L. D. Bonebrake.

At the time, L. D. Bonebrake was one of the best-educated United Brethren leaders in the Midwest. He had academic credentials (B.A. from Otterbein College and an M. S. and doctoral degrees from Muskingum College), and he had administrative experience.

At that time, it would have been very hard to imagine a more well-respected set of names in the midwestern United Brethren Church network than those of “Lewis Davis” and the surname “Bonebrake.” Indeed, like the prophet Elisha who implored God to grant him a double measure of Elijah’s gifts, the man chosen to serve as the second president of Indiana Central University appeared to be both well-chosen and blessed.

To be the namesake of Lewis Davis was a special honor. The “father” of United Brethren higher education, Lewis Davis served as the president of Otterbein University from 1850 to 1871 before departing to launch the first United Brethren Seminary (now known as United Theological Seminary in Dayton, Ohio). In the 1880s, the students at Hartsville College (Indiana) even renamed their debating society the “Davisonian society” (which had earlier been named after President Thomas Jefferson), and twenty years later one of the dormitories at Huntington University was named after Davis.

And L.D. also had all the advantages associated with his surname. He was not ordained, but the Bonebrake name was associated with ordained ministers spread across four generations of the same family, not to mention cousins in several branches; indeed, some said that church leadership was the Bonebrake family business, including his grandfather Henry, who also was one of the early advocates for higher education. And the United Brethren Church’s seminary was named for one of the members of his family the same year that L.D. was selected to serve as president of ICU. In 1909, at least, there was no question that to have the name Bonebrake associated with your institution lay claim to the best aspects of United Brethren higher education. Even so, they sought additional assurances. Bonebrake did not accept the trustees’ initial salary offer, leaving them to wonder if he was worth a salary of $3,000 per year. Former president J. T. Roberts gave the needed reassurance by adding a few more famous names to the pile of comparisons: Bonebrake combined “the financial acumen of a [Andrew] Carnegie, with the statesmanship of a [Daniel] Webster, and the educational genius of an [Charles W.] Eliot” (Hill, 37).

Having assured themselves that they had done their due diligence the ICU Board of Trustees left Bonebrake & company to solve the daunting financial challenges with fewer than 150 students enrolled. When he took office, L.D. Bonebrake and other ICU leaders believed that it should be possible to raise sufficient money to support the college from the 50,000 or so members of the three Indiana Conferences of the UB Church. Like his predecessor, L. D. believed that it was a realistic assumption to think that ICU could enroll a total of 500 students per year from the church constituency. And beyond that stable foundation, he believed ICU could attract other students from Protestant denominations who shared their pietist ecumenical sensibilities such as the Methodists and Disciples of Christ. But of course, such potential could not be achieved without dormitories, which in turn required obtaining more land for expansion of the campus. President Bonebrake struggled to make headway. Financial support was not forthcoming and the expectations for enrollment growth did not materialize either, although enrollment did reach 228 by 1915.

In retrospect, the trustees’ selection of Bonebrake for president of ICU in 1909 was based on the wrong set of indicators. Bonebrake’s great strength was that he knew how state bureaucracies worked – particularly with respect to the “common schools” movement in Ohio, where he had served as the state commissioner for five years. But that skill set turns out not to have been transferrable across the Indiana state line. With the exception of his acquaintance with the United Brethren layperson Professor Wertz, the principal of the City High School in Columbus, Indiana (who led the Board of Trustees at that time), Lewis Bonebrake did not have the necessary contacts and working relationships with the movers and shakers in the state of Indiana, especially in central Indiana.

Even worse, despite the fact that his family had a collective reputation for being good stewards of personal wealth and household resources, L.D. Bonebrake proved not to have much business acumen. But it must also be said that he faced a desperate situation. L. D. Bonebrake was surely one of the unluckiest leaders to ever serve as a college president. It appears that nothing that he tried worked, and no one questioned his work ethic. Frederick Hill reported that Bonebrake spoke 216 times during his first two years in office. Even so, President Bonebrake displayed a remarkable lack of prudence. Several of the potential donors and business partners he cultivated were idiosyncratic personalities who had hopelessly entangled financial affairs.

President Bonebrake and the Board of Trustees all concurred with the broader outlines of the plan (for developing the land to be purchased from the Alexander Hanna estate) they wanted to advance. As their business proposition made explicit, they believed that they could offer potential investors a “splendid location.” At that time the population of Indianapolis was approaching 300,000 and “growing rapidly.” The city had already developed ten miles north of the town and eight miles east. The 1913 flood in the Western part of the city had temporarily halted expansion in that direction, which meant that the next best options for development lay to the south of the city.

President Bonebrake and the Board of Trustees imagined the University Heights community to be both beautiful and “more healthful” than other parts of Marion County in the section south of Garfield Park, which the City of Indianapolis had recently developed. The tract of land formerly owned by the estate of Alexander Hanna was located “but a short distance from Garfield Park neighborhood.” With the township’s street improvement plans already in the process of being carried out, the prospects were good for a strong return on investment. They estimated that the tract of land between Madison and Carson and north of Hanna Avenue would likely sell for $500 per lot (which was more than double the going price for the lots in the University Heights south of Hanna Avenue just a decade before). The opportunity that the Board of Trustees and church leaders were proffering to potential investors was for a limited time. By 1914, they could claim that more than $52,000 funds had been pledged or paid, but “$30,000 of regular notes” remained to be sold for people who wanted to make a wise investment.

Unfortunately, some of the real estate investors who were pushing forward this venture had interests that ran contrary to those of the university. Indeed, it turns out that the leader of the University Land Company (a recently appointed trustee) had not actually purchased the option to sell the land from the Alexander Hanna estate. To make matters more complicated, some of these same business partners were pushing for the inclusion of a “Negro Clause” which would have further restricted the sale of lots. (They had already agreed to include the Temperance Clause, prohibiting the sale of alcohol, which had been a feature of the sale of all lots in University Heights since 1904.) Finally, in return for selling all the lots from the Hanna estate. The University Land Company proposed to give Indiana Central a total of 20 acres, which was insufficient to enable the kind of campus expansion that would permit healthy growth and development.

At almost the same time that the five stipulations of the business proposition had been formally stated in a memorandum dated Dec. 31, 1913, the Executive Committee of the Board of Trustees took several actions of its own (in a meeting held Dec. 30th). Thereafter, it dropped negotiations with the University Land Company, relieved President Bonebrake of financial management authority, and appointed Irby J. Good ’08 to take over financial operations for ICU in the position of “business manager.” (Thanks to the careful work of Professor Frederick D. Hill, we know enough about what was happening at Indiana Central during this period that it is possible to reconstruct the actions that took place prior to the beginning of World War I. See Downright Devotion to the Cause, pp. 66-70 to learn more.)

Even though I.J. Good was much younger than President Bonebrake, he already had displayed prudent leadership in the administrative and teaching responsibilities that he had shouldered over the previous five years. Members of the Board of Trustees believed that this 28-year old alumnus could be trusted to carry out due diligence on behalf of the executive committee of the Board. In making the move toward a more differentiated mode of financial management, the trustees not only designated a “prudent operator” with greater skills than the President, they also prevented the university from jeopardy.

Shortly thereafter, the Board of Trustees permitted I. J. Good to bring forth the outlines of a new set of coordinated fundraising initiatives that would be carried out by him working on behalf of the Board of Trustees and the Church of the United Brethren in Christ. Within a few months, Good had reorganized the financial administration of the college. We know what the details of this second initiative were because they were published the following October in the next issue of The Indiana Central Bulletin (see page 7).

The collective import of these actions also sent a signal about the leadership of the institution. At the insistence of members of the Executive Committee of the Board of Trustees, Irby J. Good’s photo appeared on the cover of the next issue of the ICU Bulletin, which displayed the master plan. Good resisted this action, probably out of respect for President Bonebrake, whose own photograph is nowhere to be found in the October 1914 issue of the publication. By this point, President Bonebrake was already on his way out the door. The question is how that exit would take place.

The selection of a business manager who was competent to play the role of “prudent operator” apart from the Chief Executive Officer – to use the business parlance for a differentiated mode of financial management – did not take care of all of the university’s problem. During Bonebrake’s final year as president, the Board was asked to consider a proposal from an(other) entrepreneurial trustee who proposed to use the proceeds from the sale of the property to create two endowed chairs. The trustee in question proposed that he should be appointed to be the first holder of that chair. This same trustee thought President Bonebrake should be given his own endowed Chair in Education.

At this point, Bonebrake’s health was suffering and it must have been tempting to him and possibly others to think that he might continue to serve the institution without bearing the burdens of the presidency. But there was also a matter of annuities. President Bonebrake would receive $1,500 per year (roughly the salary a professor received at the time) for the rest of his life. No doubt this latter provision concerned the trustees. (There is another sad fact of the matter. Bonebrake was supposed to have been paid a total of $17,000 for the period of time that he served as President. At the time that he retired due to ill health, ICU still owed him $10,000, and when the debt was finally settled following his death, the heirs of Bonebrake received about $4,000. So Bonebrake was hardly the only leader at Indiana Central who lacked prudence.)

Despite the fact that he had been named business manager earlier in 1914, Irby J. Good had not been given an opportunity to review the contractual details of this complicated set of purchase agreements, property exchanges, proposed endowments, and annuities prior to the presentation to the Board of Trustees. One of the first things that Good did after becoming Acting President in the fall of 1915 was to initiate an investigation of these financial irregularities associated with the endowed chairs proposal. Fortunately, the Board appears to have given initial approval to the proposal, but enough qualifications and caveats were inserted that ICU was later able to pull out of the venture. Thereafter, the ICU Board of Trustees was more disciplined about which proposals it considered, and the next president displayed prudent as well as effective leadership.

Another five years would pass before Irby J. Good was able to arrange for the actual purchase of property from the Alexander Hanna Estate. By that time, the university was able to obtain sufficient property for development purposes (30 acres with options for future transactions) without the kinds of binding restrictions that rightly should concern trustees. Over the next seven years, President Good built four new residence halls, and the capacity of the college quadrupled–a remarkable set of achievements for any president. During the 1930s, as many as 500 students lived on campus at the same time. Despite the Great Depression and World War II, Indiana Central survived. Following World War II, stable finances and steady growth became a feature of institutional life during the presidency of I. Lynd Esch (1945-1970). But if Irby Good had not taken over the financial management of Indiana Central when he did, it is hard to imagine this kind of positive trajectory for the institution. More than likely, it would have failed.

To be sure, not all of Irby J. Good’s decisions were prudent. He made his share of mistakes. And at times he certainly was too cautious. But we remember his leadership and honor his name on campus because across a period of three decades, he endured against the odds and led the institution forward. By contrast, to my knowledge, there has never been a serious proposal to name one of the university’s buildings or programs after our second president.* Whatever one may say about the names Lewis Davis Bonebrake received at his birth and the reputation he achieved prior to coming to Indiana Central University, in the context of the history of our institution, he was no I. J. Good!

As always, please feel free to contact me at missionmatters@uindy.edu if you have questions or feedback. Remember, UIndy’s mission matters!

*Please Note: Former V. P. and Interim Provost David Wantz once joked that UIndy might consider renaming the Krannert School of Physical Therapy, the Bonebrake School of Physical Therapy. That would show that we have a sense of humor anyway!