Mission Matters #70 – Beyond the Dry Landscape: Student Life at Indiana Central, 1945-1962

By Michael G. Cartwright, Vice President for University Mission and Associate Professor of Philosophy & Religion

This year we are exploring marks of excellence that can be discerned in the past and present of our institution. Virtues are displayed in the context of practices and social relationships, they reflect moral traditions, they are embodied by exemplars, and they are sustained by institutions such as universities. In MM #66-69, the focus was on the virtue of temperance. In this issue, I explore what happened after the loss of the temperance tradition at Indiana Central College.

I find it hard to imagine what our university campus might be like if Prohibition of the sale and distribution of beverage alcohol had not ended in 1933. I know I am not the only one who is unable to inhabit that mental space. But if we are to fully grasp the world in which Irby J. Good and the faculty and staff colleagues were living from the founding days in the fall of 1905 until the early months of 1933, we need to be able to see the world as they saw it during those first three decades. I will not attempt to speak for anyone else on this matter. What I know is that I find it difficult to imagine the world BEFORE REPEAL because of all the behavioral discrepancies between the legal standards and the lived reality, what might be called the problem of ethos that is a perennial struggle for the wider society as well as for faculty, staff, and students at residential colleges and universities like UIndy.

Join me as I try to make sense of what happened at Indiana Central College as the campus transitioned from temperance sensibilities defined by Irby J. Good, who appears to have little if any tolerance for ambiguity, to the student behavioral codes of President I. Lynd Esch, a principled pragmatist who continued to uphold the rule against alcohol on campus, even as he made space for Indiana Central to become a more diverse community. As I explained in MM #69, the story of “Temperance Lost” at ICC is complicated by several factors. These include faculty conflicts with President Good and the shifting social mores brought about by World War II and its aftermath, all of which “restructured” American society in many ways, bringing with them increased federal oversight for social welfare, transportation infrastructure, and higher education.

All of which means that in order to tell the part of this complicated story of the different ethos associated with the world “after Temperance” at Indiana Central College, I must explain several overlapping circumstances: 1) What happened in Indiana and/or American culture in the wake of the Repeal of Prohibition; 2) What happened at ICC after a new administration took over, especially with respect to the ways student conduct codes were enforced; and 3) the shifting demographics of the student body at ICC and the neighborhood of University Heights United Methodist Church in the 1950s. Only then will I be in a position to talk about the experience of (some) ICC students in the late 1950s, which in turn helps build a bridge to the 21st-century world we inhabit.

We are fortunate that we are in a position to talk with alumni from that era. I am eager to talk about my conversations with Carolyn France Lausch ’60 and Eugene Lausch ’60 about the social mores they experienced at Indiana Central during their student years. We will be in a better position to engage their stories if we first weigh the shift that took place after World War II when the emergence of a changing ethos set up new ways of thinking about law in American society.

From ‘Let’s Make the Land All White’ to ‘Law Floats On a Sea of Ethics’

The oft-quoted quip “law floats on a sea of ethics” has been attributed to Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., the great jurist and justice of the U.S. Supreme Court who wrote texts on the development of common law in the British and American contexts in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Turns out that attribution is mistaken. The actual author was SCOTUS Chief Justice Earl Warren (who in turn probably was expanding on the substance of OWH’s discussion of common law). Those of us who are interested in the role of interfaith engagement in American culture like to point out that Warren’s remarks were given at the Louis Marshall Award Dinner of the Jewish Theological Seminary, Americana Hotel, New York City (11 November 1962).

The longer version of the quotation is also worth pondering: “In civilized life, law floats on a sea of ethics. Each is indispensable to civilization. Without law, we should be at the mercy of the least scrupulous. Without ethics, laws could not exist.” There is no textual evidence that the Chief Justice had Prohibition in mind when he wrote his remarks (although a few wits have suggested that it would have been apt if he did). Even so, this statement displays the insights of a man who was a careful observer of how democratic republics do and do not work across time. Indeed, in addition to the fact that Warren’s metaphor invited his audience to think in depth dimensions, it also serves as a reminder of the historical character of both law and ethics.

Warren’s memorable statement has become fodder for the nuanced reflections of other figures in the field of law and ethics. Not all of the reflections are American. Indeed, arguably some of the best are by people who have not been shaped by American culture wars conflicts. For example, a few years ago, the Australian jurist Lex Lasry pointedly asked an audience of his peers: “how often does the law float on something other than ethics – on something other than fairness, tolerance, compassion, respect, and forgiveness?” His answer is candid: “Sadly, over the years in many of the cases that I have been involved in where the law meets politics, the law has been floating not so much on a sea of ethics but rather a sea of political self-interest and fear.”

Here, Judge Lasry is frank with himself and his audience of colleagues about the kind of negative ethos of oppression that supports laws where minority populations are ruled by narrow majorities that results in oligarchy. (Americans recently have become reacquainted with this state of affairs, but arguably this was already the case during Prohibition.) Of course, the metaphorical associations of ‘law floats’ do not align well with 1920s era posters (see MM #68) when advocates of Prohibition were urging Americans to “keep the map all white.” That kind of black and white imagination relied on the extension of the power of the majority – ownership/governance of land, settlements, local and state government – to achieve reform and impose change.

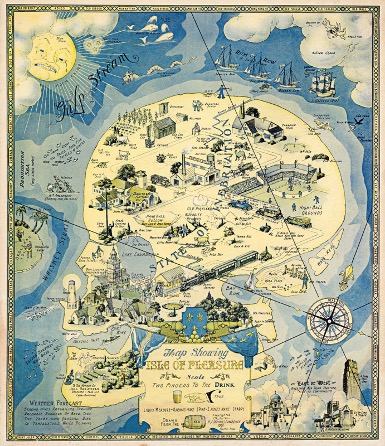

Inevitably, this monochromatic vision evoked a broad backlash of popular culture humor that reminded defenders of the 18th Amendment, the pleasures of life, and life-sustaining properties – associated with all things “wet.” These opponents of Prohibition flipped the script in quite obvious ways. My favorite work of anti-Prohibition art is the “Island of Pleasure” poster (see above), which claimed that in all directions, “wherever men drink, there is conviviality.” Strictly speaking, alcohol may not be necessary for human sustenance, but it is widely conducive to festivity.

When it comes to Prohibition, no such ethical buoyancy existed after 1926 in Indiana when the Wright “Bone-Dry” law was passed by the state legislature. Violations of the law included the use of prescribed medications in which alcohol was an ingredient. When it turned out that a candidate for governor of the state of Indiana and the leader of the Anti-Saloon League both had used such medications, these figures faced public ridicule for hypocrisy. Soon after the 1932 national election, the writing was on the wall for repeal of the Volstead Act.

In sum: Prohibition’s opponents focused on the need to align ethos with law. In the end, as the title of the third part of Ken Burns’ film about Prohibition makes explicit, the Prohibition regime collapsed because the opponents succeeded in showing the net result was to make the USA “A Nation of Hypocrites.” This discrepancy between law and ethics is part of the story we need to keep in mind if we are to understand the challenges that President Esch faced in rebuilding Indiana Central College after 1945. But that is only part of the story. However much it may fit with our own temptations to omniscience in this matter, we cannot tell the story as if the fall of Prohibition was inevitable.

Telling the Story of the End of Prohibition: Then & Now

In the final chapter of his remarkable book “Prohibition is Here to Stay” – The Reverend Edward S. Shumaker and the Dry Crusade in America,” Jason Lantzer provides a helpful discussion of the ways in which concerns that originally had been prompted by the Temperance movement were re-channeled as part of the broader set of societal reorganization after World War II. He persuasively argues against letting the “myth of failure” tell the story of what transpired precisely because the story involves both continuities and discontinuities. Lantzer believes that both must be taken into account if we are to understand the complex legacy of Prohibition.

The title of the final chapter by Lantzer, “Everything Old is New Again,” telegraphs the main point: “Drys never got a delay in the repeal process to regroup. The dry cause had been too successful for its own good. . . .Drys now faced an America that saw their reform as both a failure and wrong, despite the prevalence of their evangelical Protestantism. . . The dry cause, however, was hardly vanquished by repeal.”

Lantzer does a wonderful job of showing readers that – as with other American culture wars – the tactics used by opponents of the sale and distribution of alcohol changed, but the concern about “the problem of alcohol” did not go away. The Prohibition Party still exists, albeit much diminished. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union also is still in operation. The former national president lives in Knightstown, Indiana, and graciously responds to inquiries from researchers like me who are curious about the roles played by people such as Mother Roberts (see MM #67) during the early days of Indiana Central.

In his biography of Shumaker, Jason Lantzer provides a succinct catalog of the transformations wrought by Prohibition that are still with us, but which we do not notice in part because they have become such familiar features of the wallpaper of daily life. For example, in law enforcement, new state, and federal agencies were created. These institutional structures also created new “legal tools such as plea-bargaining and wiretaps.” (If we stop to think about the layered nature of administrative structures, we probably can trace the chain of such changes to some of the post-World War II transformations of higher education as well. More about that shortly.)

More pertinent to the challenges of telling the story of temperance at Indiana Central, Jason Lantzer traces how a shift occurred that reflected the new social circumstances of American life after the repeal of Prohibition. “The dry cause’s main response was to create a new organization, Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), founded in 1935, that inherited many of the ASL’s spiritual goals toward solving the problems of drink and stressed a collective approach to sobriety. Indeed, AA’s roots stretch back to the 1840s temperance movement and are steeped in evangelical Protestant and Catholic teetotalist ideas. . . [D]rys concluded that they could not solve the liquor problem ‘by outright and immediate suppression’ and instead had to save each drinker individually. They were, in other words, going back to the beginning.” (180)

Jason Lantzer is a careful historian. He does not make the mistake of conflating the 13-year period of Prohibition with the longer more involved saga of Temperance in American culture. The repeal of Prohibition closed one chapter in the book, but it is not the last chapter in the struggle over how to define Temperance. We no longer refer to the “Temperate Man” (or Temperate Woman if you prefer), but that is partly because Prohibition also helped to re-shaped gender roles. As Lantzer explains: “Men and women now drink together and the all-male saloon is no more. Perhaps more important, women became involved politically not only to make America dry but to make it wet.” (186)

Lantzer leaves it to others to tell the story of how Pauline Sabin’s women-led counter crusade led to the repeal of Prohibition, but for anyone interested in the transformation of gender stereotypes and the emergence of a more diverse set of women’s leadership models for college students in the 1950s, it is a story worth taking the time to learn more about. I highly recommend the second segment of the last part of Ken Burns’ documentary on Prohibition where you can learn about the intrepid efforts of Pauline Sabin, who led the successful effort to repeal Prohibition. She began by refuting the claim that Frances Willard and company had ever spoken for all women.

Lantzer offers a simple but shrewd observation about the shift in circumstances, which led to the emergence of a different infrastructure for the ethos of opposition to beverage alcohol: “New organizations such as AA were needed because the old ones had shriveled up after repeal.” (180) And so, advocates shifted to focus on the problems of the individual person and reframed their appeals via therapeutic models. Lantzer does not discuss how groups adapted the concerns of the WCTU to educate children, youth, and young adults in the context of colleges and universities. My guess is that to date no one has tackled that topic.

I did locate one set of correspondence between President Esch and a WCTU leader from 1962. The lady from Washington state wrote to remind him about the moral responsibilities of a Christian College in matters of alcohol. Esch’s response was twofold. He identified with her concern while assuring her that he personally shared her commitment to abstinence, but he gave no reason for his stance. Secondly, he indicated that the proper place for the inculcation of this moral virtue was in the home. In sum: Esch did not sign on to the expectation that Christian colleges such as ICC had a specific obligation to carry out the moral crusade for which the WCTU stood.

A Second Demographic Shift: Redefining the “We” of Indiana Central

Another aspect of this circumstance that must be mentioned is demographic change. In 1924, (see MM #69) more than 80% of the students at Indiana Central were United Brethren at a time when the total student population was 350. Thirty-five years later, the proportions had changed in ways that can’t be ignored. In between those markers, the campus had experienced some “firsts” – several African-American students like Ray Crowe ’38, and at least one Roman Catholic student, William Schaeffer ’35. Both of these young men were standout athletes, stars on the basketball court and off.

Schaeffer also is remembered by his classmates because he married Frances Hite-Jones ’37 and together, they are remembered for being the first interfaith marriage at Indiana Central. They later bought a home on the edge of the University Heights neighborhood, at the corner of Asbury and Lawrence. The neighbors remembered Bill because he drove a late ‘50s Cadillac, the kind that had large fins on the tail end of the car. When he parked it in the small bay of the garage, the back third of the car stuck out, which was a rather comical sight. By that point in the history of the neighborhood, Prohibition was long past, but there were still questions about what to do with the Catholics during required Chapel.

That is one measure of diversity: how to accommodate students when you cannot ignore the fact that they don’t share all of the faith commitments with which the United Brethren Church upholds. According to a similar report in The Reflector published in the fall of 1959, Indiana Central enrolled 752 students, which was an all-time record. Roughly one in three was a member of the Evangelical United Brethren Church (288). The actual number of students from the sponsoring denominations was about the same as it had been 35 years before, but ICC had grown beyond its own denominational base. The next highest group was Methodists (146) followed by other Protestants (Baptists, Presbyterians, Disciples of Christ, etc.). But now, ICC enrolled 29 Roman Catholics, one member of the Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter-Day Saints, and “one Moslem.” Despite having more than doubled in size over the previous three-and-a-half decades, the proportion of the population from Indiana remained very high. 686 students (or 91%) were Hoosiers, and over half (395) were from Marion County. The residence hall capacity had not changed much in the intervening period. However, more students were commuting than before.

Even so, the student body remained overwhelmingly Protestant. But now the population of non-Protestants raised awkward questions about the “house rules” particularly with respect to the required Chapel services and programs. In 1959, all of the Catholic students would have been laypeople, but by the mid-1960s, there were several novices from Our Lady of Grace Monastery in Beech Grove, Indiana, who were enrolled. And in the late 1960s, these women could be seen arriving in a burgundy van owned by the monastery. The more visible Catholics became, the more it became difficult to ignore the ways that the definition of “Christian College” was limited. At the same time, President Esch stood resolute in his defense of the independent college, a stance that fit the midwestern culture of fiscal conservatism.

As long as the involvement of the federal government in higher education remained limited, or so Esch et al. believed, robust private institutions like Indiana Central College (affiliated with the Evangelical United Brethren Church) and Marian College (sponsored by the Franciscan sisters in Oldenburg) could serve their respective constituencies to mutual advantage. By the 1970s, this differentiated economy of independent higher education began to change in part due to the availability of funds for the construction of residence hall facilities and need-based financial aid as part of the explosion of college enrollments made possible by the federal government’s Higher Education Authorization Acts.

The congregation of University Heights United Methodist Church celebrated its 50th anniversary in 1955 (the same year that Indiana Central celebrated its half-century as a college). The church directory for that year listed 769 persons (men, women, children). Of those, more than 450 lived within a mile of the church. And the majority of those lived in the University Heights neighborhood, where the denominational headquarters for the Southern Indiana EUB Conference was located in the basement of Buxton Hall; the conference superintendent, as well as the pastor of the University Heights congregation, lived on Otterbein. And after 1955, when Nelson House – the President’s home – was built, President Esch lived catty-corner to the home of the EUB Church’s bishop, J. Balmer Showers. In the later 1950s, more so than at any other point in the history of ICC, the EUB Church was a strong and vital campus presence.

The net effect was many ICC students may have felt that the church’s influence on campus was stronger than it had been during the Good years. But the EUB Church was much more focused on the charism of Christian unity than the UB Church had been, and the congregation, as well as the denomination, had the feel of a mainline Protestant denomination, which probably accounts for the fact that even before the merger with the Methodist Church in 1968, some EUB clergy had transferred. These dynamics are important in order to understand the effects of President Esch’s leadership and the ways the student experience at Indiana Central did and did not shift after 1945.

Student Conduct Codes at Indiana Central College: 1940 to 1960

With any change of college administrations, there is a shift in tone or emphasis. This was especially true of the Esch administration. In part that is because he became president at almost the same time the newly merged Evangelical United Brethren Church was formed in 1946. About the same time, Esch coined the motto “Education for Service.” It was a new day, prosperity appeared to be just around the corner, and Esch was building relationships with the business community and civic leadership of Indianapolis and central Indiana more generally.

I suspect that if you asked people at Indiana Central to make a list of changes brought about by the Esch administration, they would not list a change in the alcohol policy, but they probably would talk about the emergence of new patterns of faculty-student engagement. With enough time, students might even be able to identify the factors that helped to define the vitality of the ethos of the neighborhood in which Indiana Central was located. But he also displayed a more generous orthodoxy in matters religious. He appeared to be less rigid than his predecessor because he displayed more of a collaborative posture combined with the ecumenical language of partnership.

President Esch is more explicit about what it means for students to attend a “Christian College” and the language that he uses is more explicitly non-sectarian and more strikingly ecumenical in scope.

The Standards of a Christian College, 1947 Student Handbook:

“The Christian community has room for many different ideas, but there are some standards of thought and action which are common to all Christians. It is by such standards that Indiana Central College students are expected to live their lives. Everyone, regardless of race or creed, is created in the image of God. Proper regard for the personalities of others requires us to be honest, dependable, tolerant and reverent. Members of the ICC community, both students and faculty are expected to demonstrate these qualities and maintain the highest standards of Christian ethics in their daily lives.” (p. 3)

This is a fascinating statement. In one sense it is more expressly ecumenical than anything one finds in the previous administrations except perhaps for the initial catalog. But depending on what kind of Christian background one brings to this overview of the “Christian College,” it may be more or less opaque. For example, suppose a student comes from a family that is Roman Catholic, where the temperance ethic may not exist except in the form of abstinence and fasting during the season of Lent or as part of the sacrament of penance. By contrast, a student from a congregation of Methodists, Baptists or Disciples of Christ in Indiana probably would find this to be “mainstream” in its expression of Protestantism. What is objectionable?

We do have some student handbooks from the Good years.

“A student is expected to show both within and without the college, unfailing respect for order, morality, personal honor, and rights of others. Since the day of its founding Indiana Central College has maintained a clear cut and unequivocal stand regarding the use of profanity, vulgarity, alcoholic liquors and questionable attitudes on sex relationships. The college is not interested in enlisting young men and women to become members of its student body, nor in keeping them as members of the student body, when their conduct and habits are such as to have an undesirable influence on others.” [p. 4]

The tone of this statement is misbegotten and unfortunate. It comes across as legalistic, scolding, and strangely inhospitable as if this is not the kind of community of learning where if one does make a mistake you can recover from having failed. It is also the kind of statement that might invite the anger of students if administrators cannot live up to the highest standards of behavior. And we know that on at least a few occasions, students confronted President Good about his authoritarian tendencies.

More proportionate measures of severity and/or a less forbidding version of in loco parentis are found in the 1947 Student Handbook, revised during the first years of the Esch administration. Unlike the statement from shortly before World War II, the student conduct statement is succinct. Smoking is officially “discouraged.” Students are informed that vulgarity may lead to “disciplinary action.” Alcohol use will lead to “expulsion.” So clearly the prohibition against alcohol use remains in effect, but none of the coded language remains that temperance leaders used in the 1920s or 1930s. The language is measured. Violations are to be dealt with in proportion to the severity of the offense

This may have something to do with the fact that the students who are enrolling in the college after WWII are more diverse. (For example, a significant number of the student-athletes who were recruited to play baseball and football for the 1946-47 academic year were in their mid-20s.) This statement continues to be used for at least the next decade, but then we see signs of change, initially in the way violations are processed, but shortly thereafter in the ways rules and sanctions are listed in the ICC Student Handbook.

Eugene Lausch ’60 has also offered a perspective about how the disciplinary process operated. He was part of the first Student Court, which brought upper-class students into the process of adjudicating violations of student conduct. Gene recalls: “When I was a senior, a freshman in Men’s Hall (where I was head monitor) was discovered to have beer in his room. I participated (but did not say anything) in the disciplinary proceeding. In a meeting in Dr. Esch’s office, the young man admitted what had occurred and expressed contrition. The scales of justice seemed, based on Dr. Esch’s first comments, to move in the direction of serious punishment for the burly football player but then Dr. Robert McBride [the Dean of Men] spoke in favor of mitigation of a harsh penalty, Dr. Esch acceded to Dr. McBride’s view and the young man was allowed to stay in school.”

Absent a wider set of oral histories and/or base of knowledge, it is hard to know how exceptional such violations were at the end of the 1950s. Two years after Gene Lausch graduated, the 1962 student handbook includes a much more elaborate set of procedures for dealing with violations of the rule against possession and use of alcoholic beverages. (Note the reference to a student court.) Oddly enough, subsequent editions of the student handbook do not include that process, so the alcohol violations process turned out to be an unsuccessful experiment, or perhaps that set of provisions was incorporated in a way that did not need to be spelled out.

Regardless of the particulars, we know that questions about when, where, and how to involve students in the process of student governance became much more significant at Indiana Central after 1960. Prior to 1945, students were shut out of the process. By the late 1950s, Professors at ICC such as Marvin Henricks had started offering a course on “social problems” on a regular basis. Students had more opportunities to discuss cultural conflicts in the context of meeting their curricular requirements, and those discussions spilled over into the co-curricular activities. (Imagine students 60 years ago having debates about whether Congress should have the prerogative to overrule the U.S. Supreme Court!) By the time members of the class of 1960 enrolled at Indiana Central in the fall of 1956, the memory of the Prohibition was locked away, even as the practice of abstinence from alcohol remained.

Student Perspectives and Alumni Memories from the Late 1950s

My guess is that there are many stories that could be told about student experience with drinking alcohol during the Esch era, and I admit to the fact that I know only a few of these anecdotes at this point. (Those who have a larger raft of such tales have not shared them in venues to which I have access.) A good place to begin – as I have done in previous essays in this mini-series of essays on the Virtue of Temperance in the heritage of our university – is with the artifacts that are available to us in the digital archives of the University, namely The Reflector newspaper and The Oracle yearbooks. Combined with some oral histories, what I gather is that the rule against possession and consumption of alcohol on campus was taken for granted during the 1950s. In that respect, it is not unlike the perspective of the student writer from 1924 who identified the moral disapproval of smoking cigarettes as a “tradition” of the college.

This campus tradition also was observed and supported. At least some of the students owned the disapproval of alcohol use and voiced that concern in their own language. Consider the following example of thoughtful student commentaries about alcohol problems written by Philip Klinger’s 1959 article “The Living Death” published in The Reflector about alcoholism, which quotes a Japanese proverb about alcohol.

“First the man takes a drink.

Then the drink takes a drink.

Then the drink takes the man.”

Klinger’s comments are quite pointed, but he doesn’t employ the traditional vocabulary of the Temperance movement. In fact, his use of a non-European adage may have the possible effect of disarming his audience long enough to get his point across. I think it could have been used as part of a sermon given at a United Brethren Church. Indeed Klinger was a member of the Central Ministerial Association. This young theologue offers a succinct moral homily about the problems associated with alcoholism, but he doesn’t call for his classmates to sign the pledge to abstain from intoxicating beverages as someone speaking in Chapel at Indiana Central College might have done in the 1920s.

Everything this future United Methodist pastor says is consistent with the stance of Indiana Central. The underlying assumption is individual reform. In the 19th century, they would have thought of this as a form of “moral suasion.” In these respects, the circumstances at Indiana Central ca. 1959 fit with the dynamics described by Jason Lantzer. This is a period in which there are new patterns of engagement amid often unrecognized continuities – anti-saloon sensibilities from decades before — without any of the labels previous generations would have employed.

What I find most interesting about these two additional “exhibits” of Indiana Central’s student ethos (see MM #69) is how student conduct rules are perceived by alumni of a particular generation, and how the college and university leadership administer the rules and policies that exist at any given time. In conversations with alumni from the 1950s, it is not uncommon to hear classmates talk about that era as a time of transition defined by rules against social dancing, smoking, and alcohol consumption, each of which students are beginning to be negotiated with the authority figures in their lives.

Those alumni from Evangelical United Brethren backgrounds who were students during the first 15 years of Dr. Esch’s tenure often can tell you the names of family members who were associated with the temperance movement. For example, Carolyn France Lausch ’60 knows that her grandfather was a temperance advocate and her grandmother was a member of the WCTU. Carolyn doesn’t recall her parents emphasizing temperance teachings, nor was that an emphasis that she recalls being part of her college experience.

Alumni like Carolyn are also conscious of the changes of the previous generations. She grew up in the city of Anderson, Indiana. Her father was a businessman. Her parents were well-respected in the community. Carolyn’s grandfather, Nathan Perry France, had been a United Brethren minister in Southern Indiana. Nathan would have been a contemporary of President J. T. Roberts and at one time served as the pastor of the United Brethren congregation in Columbus, Indiana, where Samuel Wertz (chair of the board of trustees) was a founding member.

Carolyn recalls: “I knew my grandfather Nathan Perry France well and spent much time with him even though he died when I was 14. He was in the Temperance Movement and never had alcohol in his house. My grandmother Carrie Arford France was in the WCTU. She showed me her pin that, if I remember correctly, had a ribbon hanging down from it.” Carolyn doesn’t know about the direct involvement of her grandmother in the Temperance movement, but she knew her very well and spent much time with her. “She lived long enough to know Gene and even to babysit our first child Eric when we went off to play tennis.”

Carolyn’s father, Gordon France ’33, was also a graduate of ICC where he was a campus leader, member of the tennis team, and an excellent baseball player who later was inducted into the Hall of Fame along with his team who had an undefeated season. Like his parents before him, Gordon abstained from alcohol. Carolyn recalls: “In our home, it was announced that there was to be no alcohol, no card playing, and no dancing. I don’t recall my father ever talking about the temperance movement.” That generation of France practiced abstinence and passed on that moral expectation from their parents to Carolyn’s generation as a straightforward expectation without temperance pledges, etc.

The extensive overlap across the decades between three generations of the France family illustrates the formative impact of the temperance movement. This is all the more striking given that the Temperance stance was no longer actively promulgated at ICC.

Gene was involved in Christian activities on campus all four years. He says, “I do not remember a temperance movement on campus. I was deeply involved with the Student Christian Association so likely would have known.”

In this respect, we see a convergence with Dr. Esch’s own sense of the matter. Alcohol mores are best transmitted in the home. Students bring that commitment with them when they come to college, and the college’s own rules for student conduct reinforce the stance of alcohol abstinence. The fact that Carolyn is a third-generation college student whose father also went to Indiana Central would have lent additional credibility to the alcohol stance.

In the early 1950s, the France family began to change in small ways, Carolyn recalls. “When I was in junior high, I was invited to the Anderson Country Club for a square dance. My mother took a stand and Dad relented, but it’s the only time I ever heard them argue. . . . I was allowed to go to the prom two times in high school.” These exceptions to participate in dances had to do, in part at least, with the context. The country club was a place that served alcoholic beverages to members. Even though Carolyn would not have been served, the site would have been a concern.

Still later, Carolyn recalls, her parents adopted a more relaxed posture with respect to alcohol mores: “By the mid-60s, though, Mother began to sip wine and occasionally Dad did too. He didn’t drink until probably his mid-50s and then only a few sips of wine at family occasions. Mother reminded him of Jesus turning water into wine for the wedding.” Carolyn’s college experience was defined by a similar set of expectations: “At Indiana Central College, my first date was to attend a square dance in the gym, but no social dancing was allowed. I recall going to three dances off-campus beginning with the sophomore year.

Carolyn’s husband Gene adds a convergent perspective: “During the four-year period I was at ICC there was no social dancing on campus but each year there were banquets/dances or dances off-campus where social dancing occurred. I recall attending a dinner and dance for ICC students at a hotel south of Washington Street sometime during our college years, and during our junior year the all-campus “Sweetheart Banquet” (including a dance) was held at the Columbia Club. . . . There were some dances held by the Y group (Phalanx) to which I belonged at the branch YMCA (a repurposed old dairy barn) on the south side of Hanna Avenue (east of the College).”

While alcohol was not served to students on these occasions, campus boundaries with respect to social dancing closely mapped with respect to disapproval of social drinking.

For all practical purposes, then, the student experience in those years did not include alcohol consumption. Carolyn recalls her first experience with beverage alcohol took place the year after she graduated from ICC, as it took place at another institution of higher education. “When I went to teach outside of Detroit in Livonia, MI fall of 1960, Gene invited me to Ann Arbor for a football game, dinner at the “PBell” where I enjoyed a beer and the Purdue Glee Club. It was our first date as we had only double dated at ICC. From then on, we have enjoyed beers and wine together, and both sets of parents accepted that fact. Gene actually smiled and expressed ‘Whew!’ when I accepted his offer of a beer.” Gene explains: “The Pretzel Bell was a popular campus restaurant on the campus of the University of Michigan from 1934 until it closed in 1984. It was the bar of choice for the Men’s Glee Club, for Michigan Daily staff, and for many other campus groups. Much of the wall-space was filled with U-M sports memorabilia” (including, as I recall, a number of photographs of Michigan football greats.)

As this anecdote suggests, Gene and Carolyn both have good memories. In both of these cases, there are family memories about how previous generations were shaped by the lingering influence of temperance beliefs and ethos of the Evangelical United Brethren Church, but temperance was not an articulated part of the student experience at Indiana Central College. Gene recalls, “As I moved into my junior and senior years at ICC I thought about use of alcohol and decided that drinking was acceptable within my own evolved-as-a-young man moral standards. But it was only an abstract decision.” In retrospect, Gene’s hesitance to act on that decision was due to two reasons. First, “I decided that I would not drink on or anywhere near campus. My parents had strong views, especially my father, that alcohol should not be used and while not agreeing with those views, I wanted to respect the position of parents. They were, after all, providing financial and emotional support for me as a college student. Also, I had minor roles at ICC in relation to the administration of school rules (head monitor in Men’s Hall, Student Court member); violating these rules would betray a trust and make me a hypocrite.”

In retrospect, Gene suspects “there was another, perhaps unconscious reason for hesitancy to use alcohol. I think the reason probably had to do with having an EUB background. While I did not have abstract reservations about alcohol use, I think I had absorbed the notion that use of alcohol could be associated with unappealing conduct and slackness in life. Images of unambitious men in undershirts with beer bellies and the scent of stale alcoholic beverages came to mind. As I look back, I acted in a responsible way in relation to alcohol use. But I can think of a number of instances when my actions as a young man were naive, insensitive, immature, unwise, or even feckless; this helps balance things out!”

Both of Gene’s parents were alumni of Indiana Central College. In fact, thanks to Gene and his mother (see MM #49), we have a wonderfully well-developed picture of what life was like at Indiana Central in 1931-35 when Catheryn Kurtz Lausch ’35 was a student. Gene also lived in the University Heights neighborhood for over a decade – during and after World War II – until his parents moved in 1951. During those years, the neighborhood became well-established as an enclave of Evangelical United Brethren Church in which relationships between people in the college, the congregation, and the neighborhood overlapped in fruitful ways. Gene knew the community as well as anyone, having delivered newspapers to people in the neighborhood. He even remembers playing basketball in the old “Barn” or gymnasium.

Gene Lausch is also the source of one of my favorite stories about students and alcohol from this period in the history of Indiana Central College. I was curious about whether there were any bars or taverns on the southside of Indianapolis during the 1950s, and so I asked him what he remembered. I wasn’t sure exactly when the Colonial Inn Tavern had first opened. Gene’s response to my query was revealing not simply about the ethos of the neighborhood but for what it said about Gene’s own campus experience. “I am not familiar with local bars and taverns. My first alcoholic drink was a sherry that I imbibed at the Harvard Debate Tournament in January 1960. Dr. Esch generously provided funds that allowed Bob Frey ‘60 and me to go to Cambridge and participate…” (For the memories of Robert Frey’s years as a student at ICC, see MM #50-51.)

The image of a pair of seniors from ICC at Harvard shortly before the beginning of the final semester of college is striking. There they found themselves at the sherry table at the reception on the Harvard campus, feeling “awkward, desiring to fit in, acutely aware of our coming to sophisticated Cambridge from a small, obscure Midwestern school.” Both students were old enough to drink, but they would have been conscious of representing the college at a prestigious event. Gene and Bob were also on their own and it was between semesters. (They drove from Indianapolis to Boston during the Christmas holiday break.) Should they drink the sherry that they were offered at Harvard? Or should they decline? Looking back on this moment 60 years later, Gene joked about this disclosure of this solitary instance of “pre-graduation use of alcohol,” expressing the hope it would not taint his reputation as an alumnus, citizen, and lawyer.

I do not want to give the impression that young Eugene Lausch was in all respects a rule follower, but rather that where mischief was concerned, he made careful choices. Gene recalls that he participated in a number of pranks during his student years, but he “was always very careful to not do anything that would cause harm or cause institutional leaders to become upset.”

Gene’s experience is an interesting and amusing incident to lay alongside the student conduct expectations codified in the various handbooks from the founders through the Esch years. Under President Good, I think there is little doubt that this would have been a violation, and would have been dealt with as such. Given the rules in place under Dr. Esch, in the formal sense, it would also have been a matter of concern. Some faculty might have judged it to be a violation. But the fact that Lausch was legally eligible would have been a factor. I also suspect there would have been some faculty – perhaps even Dr. Esch himself – who would have viewed this as part of Gene’s education. After all, I can hear them say, the campus experience comprises only part of the ethos of a college education. Students still have to determine what they are to do when they are guests of another institution of higher education, where there another set of “house rules” are applicable. Gene could be counted on to be polite and affable.

All of which is to say that consumption of alcohol during the 1959-60 academic year was probably on the verge of negotiability. In other words, it was beginning to be treated more like the way smoking cigarettes had been processed 35 years before. Although a serious matter, it was not the ultimate violation, which would result in expulsion! Indeed, the following year after Gene Lausch and his friend Bob Frey went to Harvard, I find references in The Reflector to marijuana and other drugs. I mention this not because I think a drug problem already existed at Indiana Central, but simply that there was awareness of the dynamics of change in American culture.

Here again, I think it is important that we keep in mind the agents of such perspectives. In the late 1950s, we see ICC students wrestling with these conundrums. And this is happening at a time when President Esch and the faculty are wrestling with how to engage student leadership in sharing the responsibility for governance of the campus. This is the period when the Student Leadership Council is invented, and the Student Court is developed. In fact, Gene Lausch and Bob Frey were among the first students to serve as judges in that experimental form of student administered justice.

This is where Chief Justice Earl Warren’s quip “law floats on a sea of ethics” may be helpful for thinking about our campus’s heritage of temperance in general and the period after 1945 when ICC moved beyond being a dry campus. The stated rules for students at ICC did not change. Remember, for both of these members of the Class of 1960, beverage alcohol was not part of their campus experience (1956-1960). But as their stories also illustrate, the ethos of campus was changing during that four-year period. The marriage and family of Carolyn and Gene Lausch have taken shape within an ethos in which responsible consumption of alcohol was thinkable for them personally and in their professional lives as teacher and lawyer.

Concluding Reflection with Question: “Wet, Dry or Damp?”

To paraphrase one of the greatest storytellers of all-time, “there are many other stories” about what was said and done on the campus of ICC & University of Indianapolis in the time after temperance. All that remains for me to do is to call readers’ attention to the obvious – a shift in metaphors for how we think about our campus in relation to alcohol. Once upon a time, Indiana Central was “dry” in the sense that it was unimaginable that someone might drink alcoholic beverages and be morally responsible. The generation of students at ICC in the late 1950s was shaped by “dry” culture even though they had not been formed by the tropes and practices of the Temperance movement. At least some members of the Class of 1960 experienced the shift during and after their student years, i.e. they moved beyond the dry ethic and developed habits of what came to be called “responsible drinking.”

Inquiring minds might be interested to read the set of Reflector articles about alcohol published in 1982. Five articles written by a student affairs administrator explicated the many issues associated with alcohol. The writer simultaneously used the phrase “responsible drinking” while also casting doubt on whether there is such a thing! This particular administrator (an alumnus, class of 1959) displayed his own sense of awkwardness about how to engage college students about the consumption of alcohol — even if that aspect of their college experience was still largely located in off-campus venues such as the Colonial Inn Tavern, located on the Southwest side of University Heights.

But then, what kind of wisdom could he bring to this task from his own college experience? He was broaching a topic for extended discussion on a campus where the tradition had been – with limited exceptions – not to talk about such matters. I think this example is useful for thinking about shifting campus social mores in other areas. Regimes of “don’t ask, don’t tell” exist when communities are living in the midst of shifting circumstances when rules are in the process of being adjusted, and the campus ethos is more provisional than settled.

The quip “law floats on a sea of ethics” is a distillation based on observations of the history of (English) “common law,” which is the accumulated experience of a people across time as well as the American experiment, framed by the U.S. Constitution as amended across the past 240 years. From time to time, a particular set of laws no longer function as well as they should. Adjustments move back and forth, left and right. Ethos is always a struggle. We have no shortage of examples of this kind of adaptation of laws and ethos in relation to one another. Pre-Reformation Europe had strict laws prohibiting usury, the charging of unlawful interest. John Calvin led the way in rethinking the meaning of usury (as an abusive practice that had negative effects on poor people) as opposed to the kind of lending money at interest that served the purposes of commercial enterprises in the early modern period. British and American legal codes developed with such adjustments already incorporated.

As the categories changed, the set of precedents that provided the basis for common law reasoning also changed. And in time, the body of common law shapes the perception of what citizens imagine as morally acceptable for themselves and others. The notion that law “floats” on a sea of ethics is not always stable, of course, in part because sometimes the citizens of our society find themselves caught up in stormy weather, at least some of which is our own making. Then we find ourselves perplexed about the relationship of law to ethics, and how to find the right balance.

About the time that Indiana Central College’s own EUB Church ethos reached its apogee under the leadership of Dr. Esch, Chief Justice Earl Warren himself became the focus of controversy. That renowned conservative statesman led the nine-member SCOTUS in issuing the unanimous ruling in Brown Vs. Board of Education of Topeka (1954), a decision that was based in large part on a body of sociological evidence (visual recordings) that displayed the negative effects of segregation on the self-esteem of black children. At that juncture, Plessy Vs. Ferguson (1896) had been upheld as the precedent for more than 58 years when it was overturned. Americans, conservative and liberal alike, are still working through the challenges of developing an ethos sufficient to match the constitutional law in this case. And Warren’s SCOTUS successors have issued rulings that have clarified and/or narrowed the applicability of the Brown ruling.

Mutatis mutandis, the campus ethos at the University of Indianapolis also has changed across the span of 120 years. Beginning in the late 1990s, the rules governing student conduct permitted the use of alcohol in private residences on campus, which not only meant that alcohol could be served at alumni functions in the President’s Home but also made it possible for students living in the campus apartments to consume alcohol without violating campus rules. Students are still asked to abide by restrictions on the use of alcohol. There are some exceptions to the rule, and there is now an alcohol policy and a committee that reviews requests by groups (from on and off campus) that would like to serve alcohol on campus, and the President’s cabinet reviews changes to policies. So I have participated in more than a few of these conversations about alcohol over the years, enough that there is a running joke about “Cartwright’s only one-drink rule” – a reference to my own adherence to Temperance I (see MM#67).

I also have talked with puzzled outsiders to our campus who wonder about how we have changed our rules in these matters. A year or so ago, I had a conversation with the manager at Direct Connect Printing when I picked up the enlarged version of the “Isle of Pleasure” poster (see above) that I had printed for a campus heritage presentation. She asked me what I was going to do with it. I briefly explained. She replied: “I know the UIndy campus used to be ‘dry,’ but I see that Books and Brews opened across the street, and I understand that students living in apartments drink alcohol . . . So I hear that the place is rather damp now.” I grinned and said to her: “You know, it’s a fascinating tale. It really is. . . .”

So here’s the short version of the story: The founders imagined University Heights would be a temperance community, a place where the people in the neighborhood lived according to a set of standards not shared by all people. During the Prohibition era, those rules extended those expectations to the whole country. President Good lived in a dramatically changed world in which Prohibition defined the way things would be. (After all, no amendments to the U.S. Constitution had ever been overturned.) His successor, Dr. Esch, abstained from drinking alcohol; he upheld the United Brethren traditions in which he was raised. Esch was a fiscal conservative, who also became an agent of social change. Indeed, he is the person who – more than anyone else – made it possible for the faculty, staff, and students to live with the fact of change. A different ethos began to develop. And so, the small college of 750 souls formerly known as Indiana Central College became a university of more than 5,500 students. The use of alcohol is not permitted to be consumed on campus, except in specific instances, subject to university policies, which include Student Conduct rules, and Human Resource standards. (See policy that mandates that UIndy employees conform to federal regulations mandating a Drug-Free Workplace). The campus is not “Wet” (there is no campus bar) but neither is it “Dry” like it was in the 1950s. That is why in 2020 some folks say UIndy is just a bit damp.

As always, please feel free to share your own thoughts and responses with me at missionmatters@uindy.edu. And don’t forget that UIndy’s mission matters!–MGC