Mission Matters #71 – Hopeful Conversations about Placemaking at UIndy

By Dr. Michael G. Cartwright

Vice President for University Mission and Associate Professor of Philosophy & Religion

This year we are exploring marks of excellence that can be discerned in the past and present of our institution. Virtues are displayed in the context of practices and social relationships, they reflect moral traditions, they are embodied by exemplars, and they are sustained by institutions such as universities. Hope is a virtue that has particular relevance for placemaking, a topic that a group of UIndy faculty has spent time discussing this past year amid the challenges of the pandemic.

If you have ever stopped to consider The Crossings Mural on the second floor of the southside of the Schwitzer Student Center atrium, you have seen a magnificent example of Erika Woods’ calligraphy. “Reaching out. Gathering In. Loving One Another” (2006) is an evocative contribution to the university’s ethic of hospitality, a work of art that is one expression of what our colleague Amber Smith describes as “inclusive kindness.”

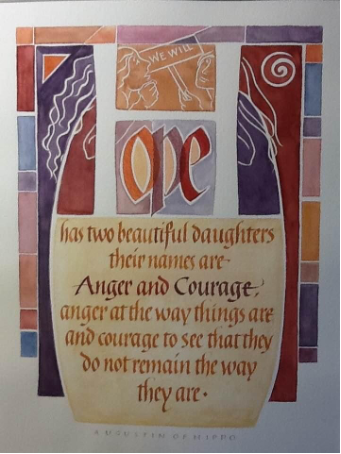

As we come to the end of the academic year, I want to direct your attention to another of Erika’s artistic works. “Hope’s Daughters” is based on the words of St. Augustine, which Erika has brought to life in a way that I find quite inspiring. In this more recent artwork (2015?), Erika has organized the space around the word Hope in an evocative way: the top and bottom panels suggest (to me) a wall that permits us to see the outside from inside a windowed space through which we see two figures waving a sign. We are invited to imagine a scene in the ongoing quest for social justice. The colors Erika has chosen are also quite evocative: red, purple, blue, but also pink, peach, yellow, and orange. These are colors (I associate with) passion and personal commitment, but they also suggest the health and vitality of the “Beloved Community.” When I encounter this particular work by Erika Woods, it feels as if I am looking out onto the world from some kind of building – a house, a university perhaps? The interior and exterior spaces are connected arenas in which “the way things are” and “the way things might be” are both present, albeit often in tension with one other.

As we come to the end of the academic year, I want to direct your attention to another of Erika’s artistic works. “Hope’s Daughters” is based on the words of St. Augustine, which Erika has brought to life in a way that I find quite inspiring. In this more recent artwork (2015?), Erika has organized the space around the word Hope in an evocative way: the top and bottom panels suggest (to me) a wall that permits us to see the outside from inside a windowed space through which we see two figures waving a sign. We are invited to imagine a scene in the ongoing quest for social justice. The colors Erika has chosen are also quite evocative: red, purple, blue, but also pink, peach, yellow, and orange. These are colors (I associate with) passion and personal commitment, but they also suggest the health and vitality of the “Beloved Community.” When I encounter this particular work by Erika Woods, it feels as if I am looking out onto the world from some kind of building – a house, a university perhaps? The interior and exterior spaces are connected arenas in which “the way things are” and “the way things might be” are both present, albeit often in tension with one other.

I would like to think that a university like ours can be the kind of place where faculty, staff, and students seek wisdom, wrestling with their anger about how things have come to be the way they are, and practicing courage to make change possible. On my better days, I am able to see the play of colors made possible by sunlight that pushes back the shadows of prejudice, injustice, and oppression. But I confess that I do struggle to sustain hope. This is why I am often grateful for colleagues who help me to think better than I otherwise would about the limits of anger and inspire me to greater courage than I might otherwise muster if left to my own dark brooding.

This past year a group of seven faculty from the Shaheen College of Arts & Sciences formed a faculty learning community to explore topics related to “Placemaking and/at the University.” Professors Bannon, Brynjolson, Cartwright, Ferreira, McKelvey, Moore, and Wynn gathered monthly beginning in October 2020 and concluding this past week. We brought different expertise, teaching competencies, and searching questions to the endeavor. For some of us – especially those like Noni Brynjolson and Kevin McKelvey, both of whom teach courses in Social Practices Art – the issues associated with “placemaking” are very familiar. Others, including myself, have come to the topic more recently. All of us, I think, discovered new insights.

We drew on our various disciplines often with disconcerting effects, such as reading about the rhetorical patterns and uses of the notion of “place” deployed by various writers. Our colleague Jessica Bannon led that particular session. Other colleagues brought insights from anthropology, art/history, and sociology as well as intercultural, theological, and ethical perspectives to bear on the topic of placemaking. I would like to think we have well represented the Shaheen College in this faculty learning community, but we hardly embody either the full range of reflective capacity or the demographic and ideological measures of diversity that can be found among the wider company of our SCAS colleagues or the wider UIndy faculty.

Part of what we discussed is the various lenses through which placemaking can be interpreted. One of those is the notion of “creative placemaking” itself, which refers to a wide range of transformative interventions by artisans and artists, activists and architects, who have worked in collaboration with funding agencies and government bureaucracies, particularly during the decade that ended in this past year (roughly 2010 to 2020). Entrepreneurs have eagerly launched business endeavors, some of which have had positive events while still others have arguably made things worse. As our colleague Kevin McKelvey has helped me to understand, one of the effects of the various initiatives was to bring into focus the tensions surrounding the kind of placemaking that failed to appreciate what was already present. More and more activists found it necessary to stress the importance of “place-keeping” as distinct from the broader variety of efforts to create ventures that were not bashful about altering longstanding patterns.

Not to be missed is the fact that institutions such as the University of Indianapolis are also locations of agency for placemaking. And within the university, faculty play different roles. Some of us live in neighborhoods that for good and ill are in the process of “gentrification” which leaves us in an odd position as would-be advocates for justice. And as Colleen Wynn explained, urban sociologists also tracked the patterns of change associated with “studentification” – dramas of change to neighborhoods that are associated with the daily lives of persons enrolled in courses — something that is perhaps even more evident around UIndy’s campus in 2021 than we might prefer to believe is the case. But then, these are concerns we may not know if we are not involved with the populations of Carson Heights, Woodlawn Gardens, Garfield Park, etc.

All of this exploratory learning about placemaking converged with the initial set of eight queries posed by the novelist and agrarian social critic Wendell Berry, with which we began, the first of which is the straightforwardly sober four-word question: “What has happened here?” Berry’s starting point, famously enunciated in his 1977 book on The Unsettling of America and elaborated more recently in such books as The Way of Ignorance and Other Essays (2004) is with the failure to exercise proper stewardship of the land, a responsibility that he lays at the door of a variety of actors, including land-grant universities such as Purdue and the University of Kentucky.

Of course, Berry’s line of inquiry can be extended further into the past, since the immigrants who settled the American continental United States. And as Chris Moore, has pointed out in several different ways during our conversations, the ways indigenous populations inhabited the land did not focus on the kind of located grids established for the purposes of settling in the Northwest Territory, which was ultimately carved into five different “states” that were admitted into “the Union” during the first half of the 19th century.

At several different points in our conversations, we asked ourselves what it would mean to engage these different “pasts” – of the settlement era and the closely related “Indian removal” – with their legacies of broken trust. These questions led to others. How can we re-engage the descendants of indigenous communities of stewardship of the land as well as neighborhoods that are endangered by commercial development schemes? What would it mean to publicly acknowledge these “predecessors” as living communities with whom we can engage in projects of restoration and perhaps even collaboration?

We talked about what it means to succeed or “fail” in placemaking ventures, we considered the effects of “redlining” on residential communities as well as the ways transportation infrastructure (interstate highways: I-65., 1-69, I-70, 1-74 & I-465), and we asked searching questions about who is responsible for the destruction of communities (like Haughville). And perhaps even more vexing, who comprises the “we” who are in a position to advocate for displaced neighbors in ways that make a difference?

Along the way, we had some rather candid conversations about how we make sense of our respective lives and careers in relation to various places including the University of Indianapolis, adjacent neighborhoods such as University Heights, and the Indianapolis metropolitan area’s various townships, counties, and complicated matrix of urban density and suburban sprawl. Most of us can name our states, countries, and cities of origin but any place-keeping we may be involved with is in communities that are not our “hometowns.” So however long we may have been UIndy employees, we are likely to still be regarded as newcomers to those we pass going and coming.

Altogether, it has been a memorable set of conversations, although I am not sure any of us would want to argue that our collaboration has produced a consensus much less an agenda for action. What I can say with a greater sense of confidence is that our conversations have increased my own sense of perplexity about placemaking here at the University of Indianapolis. The university is both the site of such endeavors and a commissioning agent. And sometimes, UIndy might be better described as a midwife involved in birthing initiatives – some small(er) and others quite big — that belong to neighboring entities, both small and large.

As such, this particular institution of higher education cannot afford to think of its multiple roles and exercise of agency as neutral or innocent. Indeed, given our self-proclaimed role as an “anchor institution for the community,” our very attempts to be strategic do implicate the university in various kinds of placemaking plots, and our neighbors are not wrong to be wary given their much more limited capacity.

This is a weighty responsibility that we embody with more or less grace depending on the particular year or the occasional controversy in which we find ourselves. Sometimes we are surprised to discover that the university is the object of anger, and at other times faculty, staff, students, alumni, trustees, and friends of UIndy are encouraged to see changes around us as measures of hope. Placemakers don’t persist when there are no possibilities for change. Authentic hope entails something more than wishful thinking.

Much depends on the kinds of stories that we find to be plausible. Lately, there hasn’t been a great supply of trust to extend to one another. Indeed, my own individual capacity for hope often has been quite fragile, plummeting while confined by surgery to repair a broken ankle and suddenly growing as a result of one or more of us have gotten that second inoculation just a couple of weeks ago. The approaching end of the imminent threat of infection by the COVID-19 coronavirus and the re-emergence of opportunities for placemaking does not close the chapter on the need to bear witness that Black Lives Matter remains. Food deserts are still a problem. And there is good reason to be angry as well as a great need for courage, my friends and colleagues.

Consequently, the “two daughters” of the virtue of Hope must be vigilant even as we continue to talk about placemaking and place-keeping at/and the University, a community where we struggle with the way things are and remind one another that this need gives in to resignation. Indeed, this is a place where our predecessors managed to survive even when others saw little more than a location on this plot of ground. Yet, some of our predecessors managed to thrive in the face of daunting obstacles.

The next two Mission Matters essays will explore placemaking amid the shadows of Jim Crow, especially in the context of the effort to create the expanded Indiana Central University campus north of Hanna Avenue and the Woodlawn Gardens real estate development, two projects that were initiated a hundred years ago this year. I anticipate that some readers will be disturbed, perhaps even angry, to learn about what transpired back then, particularly with respect to residential segregation in southern Marion County. At the same time, I hope you will be inspired to learn about some ways that our predecessors resisted injustice between 1914 to 1926 with determined aspirations. These unrecognized legacies from the older regime of Jim Crow are part of the continuing challenges that we face as children of Hope a century later even as we respond to “the New Jim Crow” with understandable anger and renewed courage.

************

Remember: UIndy’s Mission Matters!