Mission Matters #73: Reincorporating Stories of Black, Indigenous & People of Color

This semester we are exploring the implications of Juneteenth. In particular, what might it mean to reincorporate the memory of Black, Indigenous, & People of Color (BIPOC) at the University of Indianapolis and its predecessor institutions? In this first essay, I introduce the annotated timeline and illustrate one of the ways faculty, staff, and students can use this information to explore the history of engagement with people of color in our institutional history. In the essays to follow, I will discuss related quests.

Mission Matters #73

The UIndy Juneteenth Agenda: Part I–Reincorporating Stories of Black, Indigenous, & People of Color

by Michael G. Cartwright

Vice President for University Mission

This summer a diverse group of faculty and staff have been reading On Juneteenth, a short book by Annette Gordon-Reed (hereafter AG-R), which was published earlier this spring. The six essays discuss stories about her home state of Texas as well as the broader set of stories about the legacies of racism and slavery in American history. In addition to describing Galveston, the place where the Juneteenth proclamation was read on June 19, 1865, AG-R makes many different kinds of connections, including showing the relationship between family narratives she heard growing up in the town of Conroe, TX, stories of the celebrations of Juneteenth she associates with the congregation of St. Luke’s UMC, where she was baptized and learned about religious matters as a child. And she comes to grips with questions of who she is—as a “Texan” and as an “American”—and invites her readers to accept the challenge of such self-scrutiny as well.

In the next few weeks, I will be discussing her essays on the Juneteenth Conversations podcast. In the meantime, this book also serves as a prompt for re-engaging the quest to know the history of Black, indigenous, and people of color on our campus. After all, as AG-R reminds us, “nothing is inevitable. Things could have been different.” (27) And we might add: Things can also be different in the present.

Indeed, the fact that we now celebrate Juneteenth at this University is a reminder that we have committed ourselves as faculty and staff employees to make things different. We register difference, of course, in relation to the presence and absence of things. And for those of us who are visual learners, photographs often serve as powerful reference points.

In Fred Hill’s book Downright Devotion to the Cause (2002), you will find a summary of what we already know about Black, indigenous and students of color during the first few decades of our history as a university. Prof. Hill notes that “F. Jones” was the first Black male to study on this campus as a student enrolled in the Academy in 1916-17 academic year (pp. 142-143). He is referring to the photograph of the 25 students above (top-right of the second row). At that time, there were more students enrolled in the preparatory school than the college course of study.

I. Presences & Absences during “Jim Crow” at Indiana Central

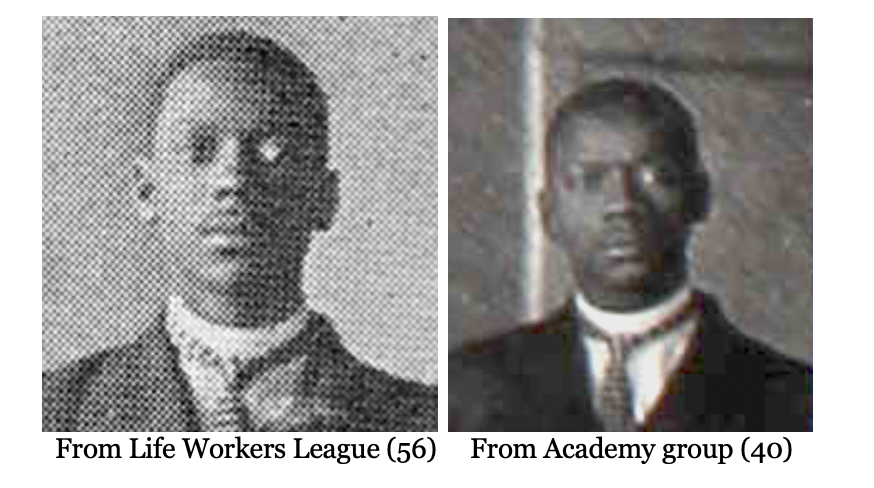

In the Digital Archives on the library webpage “Pictorial Timeline: From Indiana Central to UIndy: 1902-2007,” you will find a pair of photographs from 1917 with the name “F. Jones.” (Male students featured in the group photos of The Oracle yearbook that year were listed only with their initials and last name. Only graduating seniors of the Academy had individual photos with full names.)

The first name of this student is still unknown. We can infer from his absence from the list of 1917 graduates that, whether he transferred from another high school or was a first-year student in the ICC high school, he was not yet eligible for admission to college. There is no record that “F. Jones” ever enrolled in the college course of study at ICC. “F. Jones” also appears in the group photograph of the Life Workers League (p. 56).

Who was this man? The short answer is: we don’t know except to say that F. Jones was the first Black male student to attend this university. The following digital enhancements, extracted from two separate group photos, may inspire further research.

More than likely, “F. Jones” was from Indianapolis. Probably, he rode the urban car from Indianapolis to campus. Remember, this was a full decade before Crispus Attucks High School opened as a segregated high school for students of color in Indianapolis. According to the oral history collected from Norman Merrifield in 1980, the few Black students who attended high school from the southside of Indianapolis at that time would have gone to Arsenal Tech High School. To attend a private academy required financial resources, however modest, and would have violated the segregationist ethos of the time. The presence of F. Jones would have run counter to the prevailing social mores of the time.

Because young F. Jones was a student in the Academy, a part of the institution that was discontinued in the 1920s, we have even fewer records about him than we otherwise might have. But we do know a few things about him based on the photographs in the 1917 Oracle. He was a member of the “Life Workers League” at Indiana Central, so F. Jones identified with those young men and women in the student body who were preparing to offer their lives in Christian service. Some of these students aspired to be missionaries. Others planned to be clergy. Still others imagined lives of service as doctors and teachers in church-related institutions.

Perhaps he was involved in one of the historically Black churches of Indianapolis, such as Bethel A.M.E. Church, St. John Missionary Baptist Church, or Witherspoon Presbyterian. One of the largest Black churches in Indianapolis in the latter years of the 19th century was Jones Tabernacle African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, a congregation named for the Right Rev. Singleton T. Jones (1825-1891), the renowned bishop and orator of the A.M.E.Z. Church. Is there any family connection? That is a bit of a stretch, I admit. My guess is there is not.

Or perhaps F. Jones was sent to Indiana Central from a United Brethren agency or congregation—outside of Indiana—to train for ministry? Some would say that is even more of a stretch, but it is not impossible that F. Jones was a member of the United Brethren in Christ Church, the denomination that founded Indiana Central University And if that should turn out to be the case, that would open up another set of questions for exploration.

This is all speculation, but they are the kinds of questions that are worth asking until we locate more information about who F. Jones was. Even if we cannot connect the dots through Christian institutions, it should be possible to use public records for the period between 1910 and 1920 (census records) for Marion County to search for “F. Jones” who was somewhere between 18 and 25 years old in 1917.

The fact that he did not enroll in classes the following year may have had something to do with World War One. F. Jones might have been drafted to serve, or he might have worked to support his family if his father or another sibling had to serve. In this respect, he would have been like many other male students who were enrolled in college in 1917 when there was a call for service in the U. S. military. At the same time, there would have been other social pressures that would have discouraged F. Jones from finishing his studies at the Academy to prepare for college.

These gestures to various aspects of social context are also reminders that bringing someone’s life into focus in a way that renders them fully present entails making a variety of connections. At the same time, we probably have more access to information about our predecessors than ever before, and so we should not prematurely resign ourselves that we can never know any more about F. Jones than we knew in 2002 when Fred Hill published his centennial history.

The forthcoming “Juneteenth Timeline for Reincorporating BIPOC History at UIndy” is a tool for exploratory purposes. I have created it for use in the Office of Inclusion and Equity’s Inclusive Excellence Strategic Leadership Coalition, but it will be available for others to use as needed. This resource was inspired, in large part, by the work of AG-R. As I have tried to convey, this is intended to be a self-critical resource.

In her Juneteenth essays, AG-R recalls the tension between the theoretical and the actual as she found it in the writings and actions of Thomas Jefferson, the subject of one of her award-winning books. She applies the distinction to herself: “Abstract notions of the United States, of Virginia, — of Texas, for me at least, don’t capture why places are worthy of love” (140). AG-R is candid that being from Texas poses difficulties, for her as an African-American woman and as a historian—among other aspects of her identity. But being uncritical—of Texas as well as herself—is not an option.

For AG-R to take a critical stance “toward the object of one’s affections” is integral to the kind of fidelity and respect that authentic love demands. Although AG-R does not apply this argument in a direct way to the landscape of American higher education, it surely applies to our respectful affection for the University of Indianapolis and its predecessor institutions, especially if we want to understand how our community of learning came to be what we are in 2021.

II. Reincorporating Memories of Jim Crow at Indiana Central

In exploring the circumstances surrounding the year when F. Jones studied at the Academy at Indiana Central University, we need to learn to ask a variety of questions. Jim Crow is as good a place as any to begin. In the course of learning more about popular culture representations of BIPOC, I discovered a fascinating resource. The Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia at Ferris State University (Michigan), has existed for more than 20 years. There are exhibits and materials that call attention to the origins of the character of “Jim Crow” and the evolution of the stock characters associated with minstrel shows and other forms of entertainment in which whites adopted blackface. There is even a virtual tour of the facility that is worth taking the time to do.

As David Pilgrim, Professor of Sociology at Ferris State, explains, the origins and development of Jim Crow are complicated in ways that many people find disconcerting.

“By 1838, the term ‘Jim Crow’ was being used as a collective racial epithet for Blacks, not as offensive as [the N-word], but similar to coon or darkie. The popularity of minstrel shows clearly aided the spread of Jim Crow as a racial slur. This use of the term only lasted half a century. By the end of the 19th century, the words Jim Crow were less likely to be used to derisively describe Blacks; instead, the phrase Jim Crow was being used to describe laws and customs which oppressed Blacks.”

There is much to learn if we want to locate the ways that racist practices shaped the faculty, staff, and students at Indiana Central in the early years. In the meantime, I want to remind you that we already have access to a few sources that we shouldn’t overlook in our quest to understand contemporary representations of Black students at ICC in 1917. The Reflector newspaper did not exist until 1922. This limits the number and range of examples of the material culture prior to World War I. But we should not take that to mean that there are no remaining clues to be explored.

Consider the artwork featured in the layouts of The Oracle yearbook. Cartoon figures appear throughout the 1917 ICU yearbook as part of the design of section dividers as well as humorous images to amuse readers. I cannot determine whether these were created by students and which of them may have been supplied by the company that printed the book. It may have been a combination of both. Some of these images are “white” and some of the figures are Black.

If you have a few minutes, I encourage you to peruse the digital copy of this third volume of The Oracle. For example, on page 80 of the 1917 edition there is a cartoon figure holding a sign that reads “G’wan to the nex’ page, why don’t cha?” The youth is depicted in “blackface” and the words are examples of this dialect. What is this figure supposed to convey?

As it happens, we also know who was responsible for those images. The Editor in Chief of the 1917 edition of The Oracle was D. H. Gilliatt. The Art Editor was Will Morgan. Both men went on to have distinguished careers as faculty at Indiana Central College. Morgan studied biology at I.U., earned his doctorate, and taught students at Indiana Central for more than four decades. He was known for his academic rigor, his support for the athletics program, and he was an amateur artist. D. H. Gilliatt taught at Union Biblical Seminary in Dayton, Ohio. In 1944, he was encouraged by members of the Board of Trustees to consider applying to succeed President Good, but he declined to pursue the position. My point in identifying these men is not to heap shame on them, but rather to indicate that however the racist depictions came about, they were not isolated examples, but rather a feature of the student experience at the time.

This should surprise no one. A decade later, according to Prof. Fred Hill, a skit was presented as part of High School Day at ICU that featured the radio characters of “Amos & Andy.” In the late 1920s, that radio program would have been the most widely watched program on broadcast radio. Some historians believe that it was “the most popular show ever broadcast.” The 1928 to 1960 radio show was created, written, and voiced by two white actors, who played Amos Jones (Freeman Gosden) and Andrew Hogg Brown (Charles Correll), as well as incidental characters. This comic serial not only dominated this country’s listening habits for 15 minutes, five days a week, but also significantly influenced its daily routines.

III. The Broader Project of Reincorporating Memories of BIPOC

One of the wonderful benefits of living in a time when we are re-engaging the challenges of being a university that seeks inclusive excellence is that we have the opportunity to reincorporate the stories of Black, Indigenous, & People of Color with respect to our understanding of institutional history. To celebrate Juneteenth is to reconsider the centrality of the role that “Jim Crow” played in shaping the lives of students, faculty, and staff during the earliest decades at Indiana Central. To do that, however, we would need to come to learn to “see” the presence of Jim Crow stereotypes in our institutional history. Acquiring that kind of cultural competency is easier than you might guess, but it does require that we spend the time learning about things that most of us don’t know that we don’t know!.

Let’s revisit the cartoon on p. 80 of the 1917 yearbook. According to David Pilgrim, Professor of Sociology at Ferris State University, “The picaninny was the dominant racial caricature of Black children for most of this country’s history. . . . Picaninnies had bulging eyes, unkempt hair, red lips, and wide mouths . . . Picaninnies were portrayed as nameless, shiftless natural buffoons running from alligators and toward fried chicken.” Female versions typically were 8-10 years old with dark skin.

In the case of the drawn figure in the 1917 edition of The Oracle, the figure was well-dressed and was wearing a straw hat with flowers stuck in the band. The image diverges from the stereotype, but the use of dialect is consistent with the broader pattern of depiction. An independent observer might say of the image on p. 80 that the figure is a nicely dressed caricature, but I don’t think we can ignore the fact that this is a character that is part of the heritage of Jim Crow racism.

We are dealing with indicators here. Where the caricature of the pickaninny is used as part of the layout of the yearbook, we cannot be surprised that the story of the life of F. Jones has been lost. After all, part of the portrayal of that kind of figure is that pickaninnies are nameless. Where names can be identified—where the presence of actual people can be registered more fully—it is possible to set aside the racist stereotypes that exist in our psyches in shadowy forms. All the more reason why folks like us should attempt to learn more about F. Jones.

The question that lies before us at this juncture is whether we have the intellectual capacity, courage, and collective resolve to reincorporate these memories into the university as a community of learning. I am pleased to say that I can see numerous indicators that there is interest in learning more about the convocation of our predecessors at UIndy beyond exploring the vexing question of who F. Jones was and what the course of his life after 1916-1917 was. For example, Dr. Leah Milne and I have been in contact about the prospect of identifying the earliest Asian/Pacific Islander alumni, Agapita Obaldo ’1924 and Julio Saulo ’1928.

I hasten to add that it is also important to pay attention to what is happening on campus in the present. Earlier this month, the Department of History and Political Science hosted “Racism in America,” an event at which a pair of UIndy alumni Emily Grayce Miller ’01 and Joel Olufowote ’05 encouraged students to share their own stories in the context of talking about what it means to exist as “third culture people” This is the first event in the University Series for 2020-2022, which is exploring the theme of “Making Our Way Home.”

And that brings me back to Annette Gordon-Reed’s book On Juneteenth.

One of the few real limitations of AG-R’s eloquent book of essays is that it leaves the story of higher education institutions out of the saga. (For understandable reasons, I hasten to add. After all, you can’t do everything in six essays, etc.)

Although the author was born and raised in Texas, her academic appointment (as a distinguished University Professor at Harvard University) does not pertain directly to the subject of the story. (For the story of the first indigenous person of color to graduate from Harvard in 1665, see Geraldine Brooks’ remarkable novel Caleb’s Crossing.) No one should doubt that AG-R knows a great deal about these matters as witness her brief aside about her alma mater Dartmouth College, which originally was founded in 1769 with a mission to educate the “Indians” of New England.

Be that as it may, I suspect that if AG-R was a distinguished professor at the University of Texas or Baylor University or Rice, perhaps she would have had to include the ways in which slavery, emancipation, and Jim Crow racism have shaped the institutional cultures of those fine universities. Even so, the layered description of her experience as a child who was among the first to attend integrated schools in her hometown is a reminder that each person’s education is intricately and ineluctably embedded in institutional structures. As she aptly states, “History is . . . complicated.” (26)

The fact that institutions of higher education play significant roles in cultivating conversations about matters of race in American culture is undeniable. And our critics are quick to remind us of our shortcomings.

Those of us who work at the University of Indianapolis cannot pretend that we stand outside the complicated history of racism that exists in Indianapolis, in Indiana, etc. Indeed, the University was founded in the midst of Jim Crow segregation. In the next two issues of Mission Matters, I will describe two more quests for reincorporation the history of Black, indigenous, and people of color into our institutional history.

In the meantime, I invite you to listen to the upcoming Episodes #10-#12 of the Juneteenth Conversations podcast, where I will be discussing Annette Gordon-Reed’s essays with colleagues in the Office of Inclusion and Equity, I invite you to tune in to Podcasts #10-12. And I would be eager to hear from you about your own quests to resist Jim Crow, and challenge the history of racism near and far, and to come to grips with the ways racism has affected places that you hold dear.

—MGC September 2021