Mission Matters #77: Making Space for Black History — Part III: The Witness of Florabelle W. Wilson

by Michael G. Cartwright, vice president for University Mission and associate professor of philosophy and religion

This is the third in a series of five essays about what it means to make space for Black history at the University of Indianapolis and its predecessor institutions. In each case, one or more people will be the focus of discussion.

Telling the whole story of UIndy alumna and former university librarian Florabelle Williams Wilson (FWW) is by no means easy. I have attempted to do so while addressing groups on several occasions over the past three years. Truth be told, even when a few of us gathered on Oct. 5, 2020, at the site of her grave in Crown Hill Cemetery to commemorate her life, I still did not grasp some of the ways that she made a significant contribution to her alma mater. A few days later, I paid tribute to her remarkable life during the annual Founders Day celebration as part of UIndy’s Homecoming festivities.

After I made that second presentation in October 2020, an older alumna who participated in the Hounds Chat presentation asked me whether there were any plans to create a commemorative display about FWW’s life. I replied by saying that I did not know of any plans, but that it had already occurred to me that we should do some kind of “retrospective” – particularly with respect to the 1980 Krannert Memorial Library (KML) exhibit, The Black Family in Indianapolis: Invisible Sinew. I will come back to that prospect at the end of this essay.

In the meantime, there are some good reasons why my attempts have failed to do justice to the subject of the story. Some have to do with the richness and complexity of the remarkable person whose life and work I am narrating. In keeping with previous essays that I have written on this topic, my approach has been to let the person tell their own story as much as possible. In this instance, however, I ultimately realized that the best way to go about telling the story of the life of Florabelle Williams Wilson was to curate an exhibit in which there are multiple displays that feature her words and visage. You can find this exhibit on the UIndy Saga in the 21st Century Project page on the UIndy website.

Who was Florabelle Williams Wilson?

Based on my conversations with those who knew FWW during her lifetime and my own research (including some of her own essays, poetry, and other artistic expressions), there is little doubt that the best place to begin when attempting to describe her is the essay she wrote for the summer 1976 issue of Indiana Central’s Alumni News magazine. The piece was a short memoir piece entitled, “Reflections: Books to Bulldozers.”

“I placed my fancy red and grey hard hat carefully on the file cabinet and hurried to clean the freshly turned earth from my shoes. I had just returned to the library office following the ground-breaking ceremony for the KRANNERT MEMORIAL LIBRARY, March 23, 1976, and my mind was awash with memories of sitting behind the controls of a huge, yellow bulldozer (No. 103), feeling the behemoth respond to my lightest touch. . .”

I encourage you to read all of this brief piece if you can. It displays FWW’s personality and her enthusiasm for life and work. But even if you can’t take the time to do that, you might be able to grasp why it was that the hard hat (see photo above) was one of her most cherished possessions.

FWW relished participating in an event that she knew meant a great deal to her alma mater. The new library would be the fulfillment of long-deferred dreams and represented the aspiration of what previous generations had called “the greater Indiana Central” university.

At the same time, FWW still remembered what it was like to be the young woman who first came to campus eager to learn. Certainly, her story was about more than a transition from “from books to bulldozers,” but I don’t think she could tell the whole story without describing the experience of operating the bulldozer.

FWW’s 1976 reflection also displays some of the ways that she served her alma mater as a living witness on several occasions. She is the only campus witness from the 1940s that I have found who described the campus’ jubilation on the day the North Central Association announced that the college was granted accreditation in spring 1947.

By the time FWW had experienced the thrill of briefly operating the bulldozer to kick off the construction of the campus library, she had already exercised leadership in various ways, including organizing campus efforts to celebrate Black History Week. But once the new library had been dedicated and the books had been placed on the shelves, she and her colleagues began to make use of the new facilities in innovative ways. In particular, she became involved with the efforts of the Indiana Historical Society to collect oral histories from people in Indianapolis’ Black community.

Initially, she was a consultant for the Indiana Avenue Project; then she became involved in collecting oral histories herself. She gathered stories of Black families from the southside of Indianapolis during the celebration of Black History Week in February 1980. Those stories of lives lived — showcased using display cases, tables and an open area of the library — became the basis for an exhibit she called, Invisible Sinew. In retrospect, that exhibit turned out to be a marker in the quest to make space for Black history on our campus. The library was the location, but as “the heart of the university,” it had a symbolic status that is easy for those of us in the 21st century to understand.

The Witness of Florabelle Williams Wilson

I know there are some people who will be tempted to think that I am making too much about an exhibit. I can understand why someone might draw that conclusion.

It helps if you know something about the debates about the claims made in Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s 1965 The Negro Family: The Case for National Action. If you have some awareness of successive controversies about how to address the needs of “the underclass” in the 1970s, questions 0f “welfare reform” (1980s), the status of “unwed mothers” (1990s), and the challenges associated with governmental interventions, then you can imagine the challenge FWW and her colleagues faced in telling the whole story of the Black family on the southside of Indianapolis.

However, I would argue that to fully appreciate the power of Invisible Sinew, we have to register the charisma of FWW’s curation – by which I mean the ways she made space for Black history at Indiana Central during the period she served as an academic librarian. But it is about more than “making space.” It also has to do with the ways that she made people central to various learning projects.

Consider these four aspects:

First, there is her remarkable enthusiasm for lifelong learning. You can almost see the way she was propelled forward in seeking to learn more about the topics that interested her. She was more than bookish. She was also artistic, and she expressed her quest for learning in artistic ways. She recognized (perhaps earlier than most people at this university) the fact that students needed visual displays in order to learn about themselves and the world around them. Indeed, even before engagement-curation techniques focused on participatory experiences that museum-goers expect today, FWW had already enthusiastically embraced her vocation as an ambassador for lifelong learning.

Second, she enjoyed making it possible for people to tell their stories. She was also a diligent collector of stories, as evidenced by her exhibit The Black Family in Indianapolis: Invisible Sinew. Having been trained to gather oral history, she embarked on that path for discovery and synthesis of new knowledge. Not that she thought of herself as a primary investigator. She described herself as a “humanist” on a few occasions, a distinction that I think served to highlight her role as an interpreter and curator, as opposed to a research scholar. Several years after the 1980 Invisible Sinew exhibit, FWW drew upon her work to contribute a section to This Far By Faith, a multi-author work about Black history in Indiana. (Later, she consented to have others collect her own life story as the first academic librarian in the state of Indiana and the Midwest. It is not too much to say that she immersed herself in oral history-gathering and curation.)

Third, her passion for telling the whole story might be said to be her signature emphasis. “Let’s tell the whole story!” she would say to the children and students in her presentations about the abolitionist movement and the underground railroad. (She served as an advisor for the Indiana Historical Bureau’s 1986 exhibit about abolitionism and the Underground Railroad in Indiana before the Civil War, curated by Gwen Crenshaw.) She was not willing to settle for half-truths or misleading sagas about the past. In particular, she wanted children and college students to be given opportunities to learn the truth about slavery, abolitionism and the Underground Railroad. This was not something about which she was militant; rather, she was straightforward about it all.

Fourth, it is abundantly clear that FWW understood the Black History Project she launched at Indiana Central served to join the topic of reverence of Black history with the vocation of the university. That is, it was precisely the kind of archival endeavor that an academic library at a church-related university located in a metropolitan community in the Midwestern USA should be able to enact if it were going to serve the community where it is located. That does not mean that it was so obvious to all concerned that it would have happened without her active leadership in curating the exhibit.

Not just a storyteller, an icon

The four aspects of FWW’s witness that I have already noted are quite remarkable. They fully justify my claim that she was a remarkable exemplar of making space for Black history. But the story is still incomplete because she was not simply an oral-history collector and passionate storyteller who enabled her alma mater to fulfill its academic mission. I believe FWW also was an icon of what it means for an institution to aspire to tell the whole story. To notice that, however, it helps if you know some of the stories. Indeed, narratives render visible her life and work in ways that make it unforgettable.

One of those iconic narratives is the story of Florabelle Williams Wilson operating the bulldozer at the beginning of the construction that led to the building of Krannert Memorial Library. She relished being able to pull the levers on the heavy equipment that began the work that would lead to the creation of the library, a space that would house books and make it possible for students, faculty and other borrowers to learn. She saw herself as one person operating for the whole. She was participating in making something possible. The library would create space, not simply for books to be stored, but for stories to be told, for lives to be transformed by the discovery and appropriation of knowledge.

FWW was not naïve. She knew that the University was not free of racial prejudice. Even so, she thought of the library as the heart of the university in a holistic sense. And the quest for new knowledge surely included engaging the challenges of telling the whole story about Black history – within the means that were available to the university as it existed at the time. (Indiana Central had between 1,700 and 1,800 full-time traditional/day-division students in this era.)

I have curated a virtual exhibit about FWW’s life and work with respect to making space for Black history. I encourage faculty and staff to take some time this summer to peruse it. At the end of the exhibit, I raise some questions about what we might yet learn from FWW’s witness about making space for Black history.

I might add: these queries are by no means rhetorical. Sooner or later, the project of “telling the whole story” of Black families on the southside of Indianapolis comes back to the University’s own struggles with matters of race and poverty over the course of its first century. The Black woman who stands in front of Indiana Central in 1946 seeking admission in a world defined by Jim Crow segregation comes from a family. She has a name: Florabelle. She was the granddaughter of a freed woman whose life was no longer defined by slavery. FWW was born to a couple who participated in the Great Northern Migration, arriving in Indianapolis from rural Georgia in the early 1920s, at a time when there were very few places in the city of Indianapolis where Black people could buy homes.

In other words, the Invisible Sinew is not simply about a group of “them” outside the University; the Black history for which we must make space is also about the University itself as an institution that has sometimes failed and at other times succeeded in doing the right thing in matters of race. I am not sure there is a basis for saying how much FWW was conscious of that prospect. Perhaps people who visit the online “FWW Retrospective” exhibit that I have curated will come away with their own senses of the matter. I hope to learn more as we continue to reincorporate the life and work of FWW into our understanding of the history of the University.

Reincorporating FWW in the 21st Century

At the risk of saying the obvious, the built environment of the University is different than it was 40 years ago. The campus FWW inhabited was one where coherence had only been recently achieved. The library was intended to be visible as the “heart” of campus.

When then-President Gene Sease described the significance of Krannert Memorial Library at its dedication in 1977, he called attention to the fact that the new facility was “really three buildings in one,” because it combined a newly enlarged library facility, a learning resource center, and a new executive suite. In that sense, Sease said, “It is truly a dream come true,” as well as “a symbol of the academic progress and growth of the university.” And as such, KML would serve as “the heart of the University.”

The words that President Sease spoke on that occasion were already emblazoned on the walls adjacent to the circulation desk, proclaiming to all who entered what it meant.

The Library

The Treasury of Wisdom

The Heart of the University

The physical design of the facility added to a sense of university completeness, which in turn informed the aspiration to locate the symbolic heart of the university in the library, understood as the treasury of wisdom. To invoke the words of Sylvia Henricks, the inscription on the lobby wall spoke “both to the past and to the future.”

I still remember the first time I read that statement. Sylvia Henricks was another remarkably astute figure, an assistant librarian who made significant contributions to the University. Based on everything I know, it was an apt reflection of where the University was at that juncture.

I am not sure, however, that that statement fully captured FWW’s own sensibilities. Her passion for Black history was for the present and the future. By that, I mean that gathering oral histories from Black families on the southside of Indianapolis was never an antiquarian endeavor for her. It was about how the struggles of the present should be understood in the context of Black Americans, understood not merely as objects (and/or victims) but also as subjects – better yet, agents – of making history.

In the 21st century, many of us are not aware that there is a story about how we have dealt with space on campus. Once upon a time, the campus lacked a centered space. Almost a quarter-century ago that changed with the creation of Smith Mall (1998), where the campus parking lot used to be. Today, we face different challenges in making space for Black history; it’s not just about the physical act of making space, but also, making space in our culture’s overall sense of what’s important.

To paraphrase Chief Strategy Officer, Neil Perdue, we inhabit “a multi-center campus,” a collection of spaces that is continuing to expand, individual spaces adjacent to one another. That doesn’t mean that symbolic centers cannot exist. They do. But we have to reimagine how we use space to represent the university.

Indeed, we have to remind ourselves where to find such perspectives.

The university of the future will continue to have multiple centers that function for different purposes: the Health Pavilion; the R.B. Annis School of Engineering; and the Shaheen College of Arts & Sciences (in Good Hall). I believe we also need to have some storied spaces where icons that represent the University’s present and future can serve as resources for our individual and collective imaginations.

That brings me back to FWW. Sometime in the next 18 months, an art installation (coordinated by Nathan Foley, Jim Viewegh and their colleagues in the Department of Art & Design) will be crafted for the purpose of highlighting the various contributors to the UIndy Saga in the 21st Century Project. We want it to be visible. We want to make sure everyone is included. How big should it be? Where should it be placed on campus? Should it be in one of the buildings? Or perhaps outside in an open space?

Earlier this summer, I spent some time talking with Marisa Albrecht, director of the Krannert Memorial Library, about this matter. One of the struggles librarians have in the third decade of the 21st century is that many of the display cases that were features of the library in the 1970s were disassembled and moved during the 2015 renovation. This is another reason why it would be helpful to remind ourselves of the roles played by FWW. The connection between physical space and space in our culture is integral. Making space for Black history is making space for people, past and present. And that has not always been the case in the U.S., or in Indiana, or Indianapolis. At our university, the life and work of FWW occupy an important part of that story. Indeed, I believe that you really cannot tell the story of the quest to make space for Black history unless you understand the life and work of Florabelle Williams Wilson, who served as an academic librarian from 1971 to 1985.

At UIndy, FWW is a reminder that knowledge inheres in people.

One of the 21st century thinkers who has influenced me is David Ford, a former university professor at Cambridge, who has written so cogently about the importance of responding to the challenges of reinventing the university by paying greater attention to practices of collegiality. We are tempted to take collegiality for granted. Indeed, if we are honest, we often act as if our peers (other faculty and staff) will be there when we need them, even if we are not always there when they need us. Ford argues that one of our greatest challenges is to cultivate “ecologies” of interaction between faculty, staff, and students where the quest for knowledge can thrive. I find his discussion to be persuasive, in part because it reminds me of how important it is to remember people like FWW.

Ford explains by quoting an observation by his friend Daniel Hardy: “Knowledge inheres primarily in people, rather than in storage facilities of books and computers.” The idea of a university, he says, might be described as a “corporate encyclopedia,” but “one that is interconnected” not simply through alphabetical order but “intrinsically through the collegiality of those pursuing different disciplines, while being in conversation with each other, and at times in collaboration.”

This belief in the overriding significance of people for what it means to tell the whole story of what a university is about is the guiding principle that informs the UIndy Saga in the 21st Century Project (2022-2024). I think that is true of other initiatives as well. Arguably, the work of the Gender Center, led by Dr. Laura Merrifield Wilson and her colleagues, is about cultivating the kind of ecology in which identity matters when considering how one pursues knowledge. I know that this is the case for those of us who have been working together in the Strategic Leadership Council, led by Dr. Amber Smith, Vice President for Inclusion and Equity.

Whatever the result of that endeavor turns out to be, we know that the work we are doing builds on what Florabelle Williams Wilson did when she launched the Black History Project in the late 1970s. And, of course, other university leaders have contributed to such patterns and practices. At our best, we know that valuing people is not simply a piety to be voiced on public occasions. It is a conviction that must be carried out in the actions we take from day to day. And the work has to be ongoing.

For example, in 1988, the campus began a tradition that many people at UIndy cherish, the Celebration of the Flags. Did you know that some of the earliest gatherings took place in KML? And for a time, the eastside entry to the library was where the initial collection of international flags was placed. Later the ceremonies took place in the Ruth Lilly Performance Hall of the Christel DeHaan Fine Arts Center, then later still at the Atrium of the Schwitzer Student Center, before we developed the custom of processing the flags around Smith Mall, as we now do each October.

I recall attending that event for the first time in October 1996. It was quite a juxtaposition: The flags had been placed on the library walls encircling the space with the words on the opposite wall. Here was an interior space used simultaneously to remind the campus community that the library was a place where books and international students (as well as faculty and staff) were to be treasured, because of what they made possible at the university. Indeed, it was a space where “the whole story” of international engagement at the university could be displayed. In due course, those stories included the life of David Manley (1923), a native of Sierra Leone, who was the first person of color to graduate from the University, the first editor of The Reflector newspaper and a person who distinguished himself in many other respects.

In other words: The story of the University and Black history converge at multiple points. How could it be otherwise? The question is, do we want to know the whole story about how we came to be the university we are? FWW serves as a wonderful example for those of us in the 21st century who have embarked on the project of telling the UIndy Saga.

You may have noticed that we are giving buttons to people who have told their stories. One version displays FWW’s words: “Let’s Tell the Whole Story!” (Come to the next UIndy Saga Open House, scheduled to take place on Sept. 9, to get your button!)

I have come to believe that it is this last aspect of FWW’s witness that may be most important for those of us in the 21st century to emulate. She understood herself as both a participant in history and a keeper of the stories for those institutions of which she was a member – the Williams family, the congregation of the Presbyterian Church USA where she and her family worshiped and served, and the university where she worked, which was also her alma mater.

There is much that we do not know — perhaps will never know — about FWW’s life and work. At this point, I don’t think we are in a position to assess the degree to which she may have posed challenges to the institutional culture of the University at a time when other kinds of storytelling were more strongly affirmed and/or legitimated.

On another occasion, I may try to tackle that conundrum, but for now I simply want to convey my gratitude for the remarkable contributions of Mrs. Florabelle Williams Wilson ’49, who served as the director of Krannert Memorial Library, the first Black woman to serve as an academic librarian in the Midwest and the first African-American to have faculty status at Indiana Central University. For these and many other reasons, she received the Distinguished Alumnus Award in 1982, and four years later, she was granted an honorary doctorate of humane letters for the many ways that she made it possible for students, faculty and staff to learn through their use of the Krannert Memorial Library.

For these and other reasons, I have come to think of FWW as one of the most important icons for the UIndy Saga in the 21st Century, not only because she kept the stories and told the stories, but because of her commitment to telling the whole story. FWW’s quest was not naïve. — there will never be an occasion in which we will know everything; she knew that to be true — but she offered a hopeful witness about what is possible to learn when we are immersed in the quest to know ourselves and the world around us.

I am so pleased that the effort to reincorporate the memory of FWW has resulted in several remarkable results. This past spring, the students in Jim Viewegh’s Portrait Painting class in UIndy’s Dept. of Art & Design took on the challenge of painting FWW’s portrait. I understand that several of the paintings are still in the process of being completed, but on May 12, we exhibited a pair of portraits at the Open House for the UIndy Saga in the 21st Century. Aubrey Doyle’s portrait, which exhibits FWW with the Afro hairdo that she wore during the latter part of her life, captures some of this iconic status. Copies of the first page of the FWW’s 1986 oral history form the background of the portrait.

Making Space for Blackness in the Present

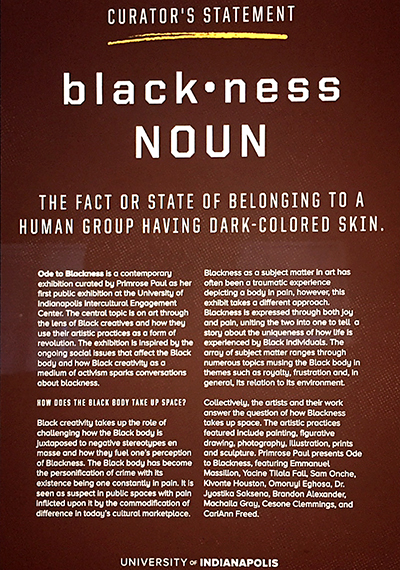

The word “immersive” also turns out to be an apt choice to describe a current student-led endeavor on campus that serves as a reminder that conversations about the Black experience are not solely about history, but also are focused in the present. I encourage you to take some time this summer to visit Ode to Blackness, which recently opened as the inaugural exhibit in the Multicultural Laboratory Space adjacent to the Office of Inclusion and Equity on the second floor of Schwitzer Center.

As curator, Primrose Paul ‘23 has not only posed the question, “How does the Black body take up space?” but also centered the narrative focus on stories of “the uniqueness of how life is experienced by Black individuals.” That she has done so in the Schwitzer Student Center also says something about the University in the 21st century. The student experience at UIndy is no longer monolithic (if it ever was), and the campus is no longer “centered” with respect to the quad of buildings formed by Esch Hall, KML, Lilly Science Hall, and the Schwitzer Student Center, redesigned in 1998 around the Smith Mall. But in the wake of the murder of George Floyd, the experience of COVID-19 and the related isolation students have experienced, there are new ways to think about the Black body.

There are more questions to think about than we have engaged to this point. Ode to Blackness displays a greater range of possible interactions than perhaps many of us have recognized, and in that sense, it challenges us to reimagine our relationship to blackness. That is true for people who identify as Black, and it is true for those of us who occupy space with white identifications.

To be sure, Primrose Paul’s exhibit is a different kind of curation than what FWW carried out four decades ago, when she collected oral histories of Black families on the southside of Indianapolis. Then, FWW used the facilities available to her, specifically, the Krannert Memorial Library, which at that juncture had an iconic status of being “the heart of the University” to be the site of a public exhibit. The exhibit made photographs and artifacts from the past available not only for student engagement but also for engagement by Black families, many of whom had never been on campus before. It was a chance for Black students and community members to learn about the ways their respective histories and personal experiences helped to tell the story of a broader set of patterns.

Conclusion

Exhibits are one obvious way to make space for Black history. We need to pay more attention to what curators make possible. Thanks to FWW, something invisible – the essential strength of many of the Black families living on the southside of Indianapolis – was made visible in 1980. Likewise, something that was hyper-visible at the time – notions of pathology about the African-American experience – was challenged in such a way as to lead students to think about their own experiences in new ways. In this way, the exhibit was doubly immersive.

Forty-plus years later, Primrose Paul’s curated exhibit, Ode to Blackness, in the Schwitzer Student Center is also immersive. I invite you to see it for yourself and describe your own responses to the curated art in the exhibit — the art of UIndy students like Kivonte Johnson, the poetry of CariAnn Freed and other artists from various places, including Nigeria.

Meanwhile, the UIndy Saga in the 21st Century Project is still unfolding. We have adopted FWW’s signature phrase, “let’s tell the whole story,” as our motto of choice for this two-year venture. We cannot pretend that we will know everything that can be known, but we have been gratified to see that there is interest on campus in gathering oral history, etc. And we hope to be able to engage student interests. Given what Primrose Paul and other students at UIndy have already done, the challenge, it seems to me, is not whether students will have something to offer; it is more a question of whether those of us who are leading the project will be able to find effective ways to engage student initiatives like Ode to Blackness.

Meanwhile, I am still wrestling with the question posed by an alumna who wondered if the University had a display devoted to FWW’s life and work. If we had such a display, where might we put it? And how might such a display help us to tell the whole story about the University as we continue to make space for Black history? As part of the UIndy Saga in the 21st Century Project, we have the privilege to continue that work as part of the mission of the University of Indianapolis. Please join us. Remember, UIndy’s mission matters!