Mission Matters #76: Making Space for Black History — Part II: Learning “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” at UIndy in 2022

by Michael G. Cartwright, with Tremayne Horne

When Tremayne Horne stands before us at our University’s Juneteenth celebration later this month and sings James Weldon Johnson’s great anthem, I anticipate feeling – well, jubilant. I have heard our colleague in the Professional Edge Center sing “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” on several occasions now. His baritone voice is impressive. After all, he has trained to sing opera. But I confess that there is something about that anthem that makes my soul sing with hope.

(I hope you will join us Friday afternoon, June 17, as we celebrate the University’s second-annual Juneteenth celebration.)

I suppose that sense of hope is why I continue to teach and learn the three verses that were originally written for 500 children to sing at the (segregated) Stanton Elementary School in Jacksonville, Fla., in February 1900, on what would have been Abraham Lincoln’s 91st birthday. More about that occasion later.

First, I want to introduce you to the song, and share some of the reasons why it is meaningful to folks like Tremayne (and me!) to sing it.

Thanks to YouTube, there are many excellent performances of “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” available. I encourage you to listen to one of these:

- Alicia Keyes’ rendition includes an inspiring video montage from Sept. 11, 2020.

- The choral version sung by the Morehouse College Choir is quite stirring.

As good as such performances are, they cannot suffice for what happens when people gather to celebrate the good news that freedom has arrived. The ancient Hebrew prophets sang, “How beautiful on the mountaintops are the feet of those who bring good news!” In some quarters, such songs are called “jubilees.” They are closely associated with the celebration of emancipation from slavery.

Juneteenth, of course, is the occasion when members of the slave community in Galveston, Texas, learned that the Civil War was over and they had been set free. Depending on the particulars of local history, jubilant celebrations have taken place on other dates, including Jan. 1 [associated with the watch-night tradition of African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Churches], and still others celebrate on Lincoln’s birthday. All of these are examples of Black history for which we can and should make space.

As we do so, we need to take the time to examine the intersections of our own institutional history with those of historically Black colleges and universities. With the formation of the Jubilee Singers of Fisk University in 1871, Black singers began to perform in various locations around the U.S. and even in Europe. Such performances were troubled, because those who had been formerly enslaved struggled with what it meant to sing the “sorrow songs,” as author W.E.B. DuBois described them. Inevitably, the embodiment of Black music by Black singers involved representation of the race, exhibiting some of the “giftedness” (DuBois) of the Black Folk. This, in turn, produced debates about whether to focus efforts on the cultivation of the “talented tenth” (DuBois) or “more practical training” (Booker T. Washington) in the manual arts.

I do not know when jubilee songs first came to Indiana Central College (ICC) – which would later be renamed the University of Indianapolis – but my guess is that ICC students encountered them elsewhere before such offerings were brought to campus. For example, it is probable that when 1929 alumnus and first-year faculty member Don Carmony joined Senate Street YMCA in 1930, he might have encountered “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing.” Almost certainly, he would have heard it performed later that year, when he addressed the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) at the state convention in French Lick, Ind.

A few years later, at a time when there were very few people of color on campus due to intersecting patterns of Jim Crow segregation, a group of Black students formed a Jubilee Quartet at Indiana Central. Although they did not officially represent Indiana Central, the Jubilee singers were well-received in various churches and even in some of the clubs on Indiana Avenue. They also performed on campus. We know that Norman Merrifield, choral director at Crispus Attucks High School, brought octets and other choral ensembles to Indiana Central as early as 1941 and on multiple occasions in the 1950s. James Weldon Johnson’s anthem would have been part of their repertoire. By the mid-1970s, thanks to Florabelle Williams Wilson (learn more about her in the forthcoming Mission Matters #77), the College was celebrating Black History Week in conjunction with Lincoln’s birthday, and students at Indiana Central would have encountered “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” at the required convocation, and quite possibly on other occasions.

During the half-century between 1930 and 1980, more students at Indiana Central would have encountered the anthem. Many people in the convocation of our predecessors were beginning to learn “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing,” more than 40 years before we started celebrating Juneteenth.

All of which is to say that the opportunity to learn to sing the National Anthem of the NAACP has been around for a while now.

As Titus Kaphar said so eloquently during his November 2019 visit to our campus, these matters are personal, precisely because the struggles for equality and social justice touch our families, our institutions, and our very lives. The opportunity to engage in these struggles, I believe, begins with taking the time to stand in solidarity with those whose lives have been shaped by the racist practices of the culture around us.

To make space for Black history at UIndy in the 21st century is not only to reach back into the past and rethink how we see ourselves in relation to the legacies of slavery, Jim Crow segregation and civil rights for all people. Making space for Black history provides each of us with an opportunity to realign how we think of our relationships with our UIndy colleagues, those with whom we share the struggle to overcome the problem of the color line.

One way to do that is to talk about something we share, such as how we have learned to sing “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing.” Here is Tremayne’s story from a conversation we had shortly after spring break in April 2022.

Tremayne Horne’s Story

I am sure there are occasions when Tremayne doesn’t wear a tuxedo and a bow tie to sing before a group of people, but he was wearing one the first time I heard him sing “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” — at the Celebrating Black Excellence Dinner in February 2020, shortly before COVID took over our lives. But in addition to his attire, I remember being impressed by the power and confidence with which he sang the anthem that I also love.

At UIndy, Tremayne Horne is a member of the Stephen F. Fry Professional Edge Center, working with students from the arts, communications, social sciences, and humanities. He also serves on the Retention Task Force, is a member of the Campus Connectors team and is a part of the New Student Experience committee. I asked him to comment on the various roles he plays at UIndy. “It has been a pleasure to give back to the University so that we can support our students in achieving and reaching the next level of their lives and careers,” he said.

I first came to know Tremayne in the context of the University Seminar for Faculty and Staff that I offered in spring 2020 – a lunchtime endeavor that shifted from in-person to virtual mid-semester. Thanks to the goodwill of Tremayne and others in the seminar, we were able to complete our agenda despite the pandemic challenges. It helps to have someone like him in a seminar about stewardship of the University’s mission. He is a passionate fellow who is not afraid to disagree with folks if it is about something that matters. On the other hand, he is by no means disagreeable. Indeed, he is very congenial.

Tremayne recently turned 38 years old. You don’t have to talk with him long to discover that he has many varied interests, including, but not limited, to the arts. Singing opera, mentoring youth, and enjoying a rollercoaster from time to time are also on the list. One more thing: he is also engaged to Brittany Collins. So, someday soon, he is going to be married.

Our shared love for this great hymn stems from very different experiences in life, many of which stem from patterns of racial segregation. Tremayne has probably sung James Weldon Johnson’s hymn on more occasions than I have. He tells me that he was already singing it with the adults when he was 3 or 4 years old. In the A.M.E. Church, they sang it often.

Both Tremayne and I grew up as preachers’ kids. His mother is an A.M.E. pastor. He remembers going to young people’s conferences, and singing in the youth choir. Later, he was also a participant in community choirs. “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” was part of the repertoire in each context. So, throughout his life, not just during Black History Month, he frequently has sung the song. He had the whole song memorized by the time he was a teenager. Later, I asked him if he had favorite lines from this great hymn by James Weldon Johnson. He said, “’God of our weary years, God of our silent tears, Thou who has brought us thus far on the way.’ Even to just be 38 years old, God has brought me through so much, and continues to bring me through!”

Our colleague Tremayne Horne is a graduate of the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff (UAPB), which is a historically Black university. (Originally known as Branch Normal, it eventually became known as Arkansas Agricultural, Mechanical and Normal. It has been known as the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff since 1972.) During his college years, he was part of the UAPB Vesper Choir, which performed once a week. Every concert featured an opening number, and “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” was part of the repertoire.

He enjoyed participating in the choral activities directed by Michael Bates and Dr. Heidi Gordon. These choral conductors made sure that the students understood the history of songs. If the composition the choir was going to sing was a requiem, then the students should understand the language and history of why it was written. “I thank them for the way they drilled that into us. ‘Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing’ is one of those songs they taught us to sing in the awareness that Jim Crow must be resisted. We always sang it with pride,” said Tremayne. “When you can put feeling into it, then you treat it as it should be handled. If a person doesn’t have a good understanding of it, they don’t feel it. If you do understand where it comes from, then you will realize that you can’t just do it halfway. You have to give it the passion that is due to it. You have to be able to sing it fully.”

When he was in college, Tremayne was one of the UA Pine Bluff Ambassadors, whose responsibility it was to escort guests around the campus. He had the opportunity to tell visitors about the history of the college and about student activities. He was involved in the pep squad, Union Programming Board, Baptist Association, concert hall, Student Union, and assemblies during Homecoming. He and other students involved with these activities would often sing “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” as part of event programming.

He grew up singing the song in Tallahassee at Bethel A.M.E. and later, after his family moved, in Indianapolis. He grew up hearing church musicians like Anthony Vincent, maestro and organist extraordinaire, and he recalls with fond gratitude that it was Mrs. Queen Williams who got Tremayne into opera. He chuckles as he recalls, “That woman drug me by the ear!” As a child, Tremayne enjoyed singing in the adult choir. “That is part of what I loved about my church,” he said. “We sang lots of different kinds of music. We performed gospel music, anthems, requiems and hymns.”

During our conversation, Tremayne recalled something that he did 25 years ago in commemoration of Earth Day. “I planted a tree on the lawn of the St. Paul A.M.E. Church in Indianapolis. I remember Pastor A. V. Sanders worked with me. I was about 12 or 13 years old at the time. It took a long time for that tree to grow. I bet it was almost 10 years before it ever grew much at all. It seemed like it stayed a sprout forever. In my mind, the roots are very deep. After 10 years, the tree suddenly sprouted up. It is HUGE now that the roots have grown. I gave so much of myself to that congregation.”

During COVID, St. Paul’s A.M.E. Church closed. The folks of that church weren’t able to make the transition to having services virtually, despite the best efforts of Pastor Kenda Ward (a 2008 UIndy graduate). Tremayne drives by the former St. Paul A.M.E. church building from time to time. When he sees the tree, Tremayne says, “I am moved, sometimes to the point of shedding a tear.”

These days, Tremayne is a member of Crossroads A.M.E. Church, a congregation where he feels at home and cared for, and also finds himself challenged in positive ways. Crossroads is a congregation that is also wrestling with change against longstanding traditions. In fact, in each of the congregations where he has been a member, he has encountered traditions in both the positive and negative senses of the word.

While Tremayne finds the tradition of singing “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” to be very meaningful and perhaps comforting, he also thinks there are traditions that are unproductive. He says: “Sometimes, we get stuck in our traditions. When young people come into the church and want to make change, such as athletic activities or workshops, they are often told, ‘That is not how we do it, and we don’t need to forget where we’ve come from.’” Tremayne concludes: “The old folks resist. But they will die if they are not going to engage the young people.”

By contrast, for Tremayne, singing “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” is an example of the kind of tradition that is almost entirely positive. I asked him, “Can you imagine that you will teach that song to the next generation of your family?” His response was enthusiastic: “Oh, I will definitely be teaching my future children that song.”

I will leave it to Tremayne and Brittany to work through the challenges of passing on this particular tradition in the context of their marriage as spouses who are committed to building a future for their family-to-be. But I envision Tremayne teaching a quartet of elementary school-age sons and daughters to sing James Weldon Johnson’s great hymn. That would be a lovely reminder of the original location where the song was created — that segregated elementary school in Jacksonville, Fla.

The Story of Stanton Elementary/High School

The fact that James Weldon Johnson and his brother, J. Rosamond Johnson, wrote the song for elementary school children in the segregated South does not mean that “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” belongs to the segregated world defined by “the color line.” Although the presence of Jim Crow laws and the related way of life – old and new – remain present with us, the boundaries are unstable, even where we can locate the original spaces.

Tremayne Horne’s remarks about his experience of traditions that are vital and dynamic, versus those that are declining and perhaps dying, reminds me of my recent visit to Jacksonville, Fla., during Black History Month. Earlier this spring, my wife and I were visiting St. Augustine as part of her sabbatical, and I noticed that there was a celebration that was going to take place in the nearby city of Jacksonville that weekend. The occasion was the celebration of the 122nd anniversary of the first performance of “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing.”

The gathering took place in James Weldon Johnson Park. The park is located in the downtown area of that very large, metropolitan community, which spreads out north, south, and west of the Atlantic coast. Because it is also historically significant – the first and oldest park in the city – it reflects layers of history that go back to the “village green” that was part of the earliest community of settlers in the late 1850s.

As I mentioned, we had been visiting St. Augustine, which has its own layered history, including one of the origin stories associated with slavery, in the context of Spanish colonial history. The bed-and-breakfast where we stayed was near Ponce de Leon Park, and we spent a couple of mornings exploring the Freedom Trail. The trail is associated with the Lincolnville neighborhood, which takes great pride in its heritage of civil rights. In fact, its history includes protests and demonstrations leading to the Voting Rights Act of 1964.

According to its website, St. Augustine was founded in 1565 and “is the oldest continuously occupied settlement of European and African-American origin in the United States. Forty-two years before the English colonized Jamestown and fifty-five years before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock, the Spanish established at St. Augustine this nation’s first enduring settlement.” The settlement was called Fort Mose.

St. Augustine also was the location of a short-lived settlement of Free Blacks that was formed in 1738 by fugitives who escaped slavery in Georgia and other English colonies. Local historians and park interpreters explain to visitors what the city’s Wikipedia page describes this way: “This new community, Fort Mose, would serve as a military outpost and buffer for St. Augustine, as the men accepted into Fort Mose had enlisted in the colonial militia and converted to Catholicism in exchange for their freedom.”

Although I have visited many of the Civil Rights memorials across the United States, I don’t recall encountering such a densely layered set of sites located in such close proximity to one another.

As my wife and I approached James Weldon Johnson Park, the park where the “Lift Ev’ry Voice & Sing” anniversary celebration event was scheduled to take place, we could see the pedestal where the Confederate Soldier once stood 62 feet high. Until the late 1890s, the park had been known as St. James Park, a space known for its ornate fountain. But it was renamed in 1899 after a Civil War veteran named Charles Hemmings had paid for the monument to be built. In June 2020, the Confederate Monument had been removed during the George Floyd protests of the Black Lives Matter movement, and the park was renamed yet again later that same summer.

The juxtaposition of new and old, classic statuary and modern concrete walls of the transportation terminal are poignant reminders of an unsettled present in Jacksonville, Fla., and in American life as well. The base of the confederate monument is still there. Indeed, the word “CONFEDERATE” remains on the base as a reminder of Jim Crow’s lingering presence.

We arrived about a half-hour before the ceremony was to begin, and we waited with about a hundred other people for noon to arrive. I wasn’t aware of it before, but the tradition in Jacksonville has been to sing JWJ’s anthem precisely at noon on Lincoln’s birthday, which is roughly the time when the children sang the song in 1900. At least some people around the world participate in this ritual remembrance, although it wasn’t clear to me if the time designation was by time zone, or the local time in Jacksonville.

As people have done for 122 years, the ushers handed out copies of the words of “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” A few souls knew the words by heart, but most participants were glad to have access to the handout. The person who played the music made a point of saying that James Weldon Johnson had been one of his predecessors at Grace United Methodist Church in Jacksonville. That caught my attention. I would have thought that JWJ was part of an AME congregation, rather than one of the United Methodist Church.

A local media celebrity served as the emcee for the event. Several elderly alumni of Stanton – one of whom attended there when it was an elementary school before it was repurposed as a junior high school – were recognized. They told stories about one another’s exploits with genuine affection and only slight exaggeration. And a slightly younger woman, about my age, who was still actively involved in civic affairs, encouraged people to purchase a ticket to continue to raise funds to renovate Old Stanton School, a space that is closely tied to the memory of James Weldon Johnson and his famous hymn.

The rebranding of the park, now known as “JWJ PK,” is part of a concerted effort to revitalize the downtown area of Jacksonville. Based on what I observed that day, it is not clear how well that effort is working, although it wasn’t obvious to me whether the poorly attended event was the result of lingering concerns about COVID or a lack of interest. It appeared well-organized, and the park administration seemed to be in good order.

One of the speakers was the first Black president of the Jacksonville City Council. There was a VIP section (for those people who paid to have chairs). Most folks were milling around at one of the booths or purchasing barbecue or catfish po’ boys from one of the food trucks. A few children were playing games. There were also a few people hanging out in the park who appeared oblivious to the official activities. Participation in the celebration was not required to enjoy the facilities. Above the plaza, there was a transportation terminal, which at first seemed incongruous, but, when I stopped to consider the overlapping traditions of the space, struck me as oddly appropriate.

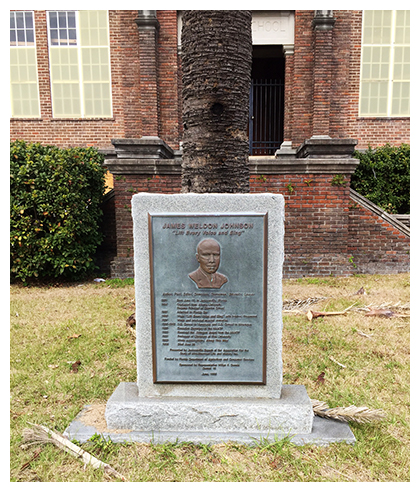

I was curious to learn more about the way JWJ’s life has been commemorated in Jacksonville, so after the celebration was over, we drove a little more than a mile away to visit the site of the “Old Stanton School.” Although the original building burned in the early 20th century, the memory of the first school for Black children in the state of Florida remains revered in Jacksonville. The brass plaque and memorial sign are clearly visible from the street, but the property is in a sad state of disrepair. There was debris scattered around the yard, with boarded-up windows over the once grand stairway entry. Although there are differences in the architecture, I could not help but be reminded of Crispus Attucks High School in Indianapolis, and be glad that Indianapolis Public Schools continues to operate it as a school in its original location.

The building that had once been christened the “New Stanton” Elementary School has long since been closed, and there are broken windows. Judging from the meager fundraising efforts thus far, my guess is that, absent some outside infusion of funds from a foundation, it is unlikely that Stanton School will be restored anytime soon. But then, the World War I era effort to rebuild Stanton School as a brick structure — an effort led by the determined principal, JWJ himself — also had once seemed daunting. Once again, I marveled about the rich and complex heritage associated with “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing,” which has become a beloved text enjoyed by children, youth and adults of all backgrounds for decades.

Memorial Plaque at Old Stanton School

Jacksonville’s tourist information office provides clear interpretation of the site: “Old Stanton High School is the site most associated with the life of James Weldon Johnson in Jacksonville. Noted Jacksonville architect Mellen Clark Greeley designed this building.” Some visitors find it odd, however, that it is not the original school where “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” was initially performed by 500 elementary school children.

“Old Stanton High School was constructed in 1917 for the specific purpose of providing a modern and safe high school building for the city’s African-American students. The new brick school replaced the rambling two-story wood-frame building destroyed in the 1901 fire,” the tourism website continues. Nevertheless, “The Old Stanton High School building is one of the most recognizable landmarks associated with the historic LaVilla neighborhood west of downtown. Although the current building is not directly related to the productive life of James Weldon Johnson, the site of the school was where he attended as a student, teacher, and principal.”

The challenge of interpreting the significance of such sites as Old Stanton School is not uncommon in the 21st century, as some traditions decline, others die, and others, in some cases, are reborn in new locations. We will need to keep this in mind as we proceed with developing our own tradition of celebrating Juneteenth at UIndy, where there is a different history of engagement with “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing.” That is where it may be helpful for those of us who are not Black and have not been raised in one of the Historic Black Churches or (like Tremayne Horne) attended one of the nation’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) to step forward and talk about what we are learning amid the University’s quest to make space for Black history.

How I Began Learning to Sing “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” at Age 15

I am confident that Tremayne Horne has sung the song on more occasions than I have and no doubt with greater talent. However, given our difference in age, I think I can claim to have sung this song for a couple of decades longer than my colleague has.

Indeed, I first began learning to sing the hymn in 1973 as a sophomore at Northside Senior High School (NSHS) in Fort Smith, Ark. (Yes, I do realize how old that makes me!) This year marks my jubilee year – a fitting marker for a half-century of experience singing and learning about a song that I have come to love, not only because of its music, but also because of its poetic text and powerful message, which I think can appeal to a wide range of Americans.

I vividly remember the first time I ever heard “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” performed. I did not realize it at the time, but this was the first occasion that NSHS had a Black History Week observance. For me, it was an unforgettable experience, perhaps in part because I wasn’t prepared for what I was called upon to do. The 2,000+ student body gathered in the gymnasium for an all-school assembly. I don’t recall knowing the purpose of the occasion, but it would not have been the first or last time that I was oblivious to something during my high school years. What I do remember is that on this particular day, we stood and sang “The Star-Spangled Banner” at the beginning (as we typically did on such occasions) and then sat down.

The emcee, one of the two or three Black teachers at the school, then came to the microphone, said that we were going to sing the Black National Anthem and invited those who wished to do so to stand to show respect as a small choral ensemble would lead us. I don’t recall thinking about the matter. I simply stood up, as did some other students around me. The song was majestic, and I can remember being intrigued by the song even though I didn’t have access to the lyrics and had trouble hearing all the words distinctively. Midway through the first verse, I became aware of the fact that most of the white students (more than 70 percent of the total student population) had remained seated, and those who initially stood had sat down.

I quickly realized that I was in a very small minority. All of the Black students were standing, along with the teachers and administrators (roughly 30 percent of those gathered), but only a few white students were standing – at the time it seemed like there were only a dozen or so — and I was one of only two or three white students in the area of the bleachers where I was standing. In fact, people around me began to hiss and tell me to sit down. The choral ensemble sang all three verses. It seemed like it took forever before it came to an end. Shortly thereafter, we had a speaker (one of the local Black clergymen) who gave a speech. I don’t recall much of what he said. I felt conspicuous in the way that many gawky high school sophomores have felt on other occasions. I didn’t like everyone looking at me.

I don’t recall having any conversations with people about that event, but I have never forgotten what it felt like to suddenly find myself in a situation in which I was standing with one group of people (most of whom I did not know) and standing against another group of people. In the days, weeks, and months thereafter, I thought about what had taken place that February day.

As we all know, memory is fallible; we sometimes “telescope” our experience with multiple events fusing together, and it is quite possible that I could have done that in this instance. Five years ago, I contacted one of the teachers from that period. He verified my account. I was relieved that I did not misremember what transpired.

Other things were going on at the time that may have contributed to its impact on my life during my 16th year. My parents were getting a divorce. There was a lot of social turmoil in the news — abroad, Vietnam; at home, the civil rights struggle; and so on.

In 1973, Northside High School in Fort Smith, Ark., was still in the process of working through the integration of Black students from the recently closed Lincoln High School. For a portion of the year, police guarded the halls. I don’t recall all the reasons why, but I wrote about that circumstance in my “book of memories” for 1973. Once that year, I was present when a fight broke out between two guys my age – one Black; one white – that involved the use of a knife. No one died, but blood was shed — the result of a racist taunt initiated by a group of white kids. Afterward, I asked myself why I stood by that day. Would I continue to stand by? Would I ever stand up against racism?

From day to day, I had encountered people who said and did things that expressed hatred and disdain for Black people. It was part of the culture in which I was raised. My family participated in the rural version of “white flight” when I was in second grade. In junior high school, I had classmates who were Black, some of whom I got to know. But in my high school years, I began to work with people who were Black and could begin to see the discrepancies in the ways that they were treated. Gradually, I began to learn to question my own white privilege, even as I confronted the challenges of poverty. The process has been slow, to be sure. But the anthem by James Weldon Johnson remains an ongoing reminder for me, and I continue to learn from its lyrics.

Higher education provided some opportunities to learn more. During my college years, I had the opportunity to hear fellow students perform the song, and in some instances, I found my way into conversations with Black students about their perspectives on racism. I began to register the power of the JWJ’s rich metaphors and started to understand the distinctive features of the Black journey from middle passage through slavery and reconstruction and on up the hill of Jim Crow segregation. I learned more about the anthem in seminary. Black History Month at Duke Divinity School was rich as well as deeply poignant. Duke University had only recently been integrated. Two of the faculty at the Divinity School had been part of the first classes of Black students to graduate from Duke University in the late 1960s. We sang it during Black History Month. We discussed it in the required course on Black Church studies.

During my seminary and grad school years, I also learned more about African-American sacred music, including the spirituals in the two-volume Book of American Negro Spirituals,” which happens to have been edited by James Weldon Johnson. I learned about the intricate ways that the spirituals drew upon the Hebraic traditions of Exodus and “the Jubilee Year” – the year following seven cycles of seven sabbath years – that exceptional season when debts were forgiven and social relations were to be reset.

That biblical vision of emancipation informed the exilic prophets of ancient Israel, and it also inspired poetry found in some of the spirituals like “Go Tell It On the Mountain.”

There came a day when I took my place on the faculty of a selective liberal arts college in Western Pennsylvania. At Allegheny College, I was asked to put together the program for the college’s first celebration of Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday. We used JWJ’s hymn then, too. I was asked to develop a course or two for the curriculum. I embraced the opportunity to push beyond my area of specialization. For a time, I taught courses on Black Religion and Black Radicalism, as well as the Novels and Essays of James Baldwin. And I was part of several symposiums and interracial scholars group projects in which we explored prospects for racial reconciliation and traditions of interpreting Christian scripture in the Historic Black Church communions. I have written articles in which I have quoted the lyrics, and I have reviewed books the titles of which allude to James Weldon Johnson’s memorable poetry.

I have some favorite phrases: From verse two:

“Stony the road we trod,

Bitter the Chast’ning rod,

Felt in the day that hope Unborn had died,

Yet with a steady Beat,

Have not our weary feet,

Come to the Place for which our fathers sighed.”

When I got to UIndy, the celebration of MLK Jr. Day was not an official holiday. Later that changed. For a time, we had an abbreviated schedule of classes followed by a convocation event. I remember hearing Mr. Geoffrey Kelsaw lead the Voices of Worship Gospel Choir performing JWJ’s song. I thought they did a pretty good job of singing it. But each time they performed the song, I remember thinking, “I wish we would all sing it with greater zest.” That only happens, of course, when a community of people knows the song well enough to sing it with confidence. As it happens, I don’t think I have ever been in a setting where someone wasn’t learning to sing it and/or was hearing it sung for the first time. But that is part of what I like about the experience. Participating in “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” is not about how much you already know. It is about discovering how much more there is to learn from the emancipation quest.

I haven’t taught undergraduates on a regular basis for 20 years, but I still enjoy introducing people to “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” in various adult education settings. In fact, the same week that UIndy celebrates Juneteenth, I will be leading a conversation in Brown County, where we will celebrate Juneteenth through music. I am collaborating with children’s librarian Samantha Hyde and her husband, Makobi Sylvester, a graduate student at the Jacobs School of Music at Indiana University. On this occasion, we will also sing Bob Marley’s “Redemption Song.” So, in addition to singing “’til victory is won,” we will talk about what it means for the predominately white population of Nashville, Ind., to “emancipate ourselves from mental slavery.”

I will also tell the story of how 500 school children at the segregated Stanton Elementary School in Jacksonville, Fla., sang it for the first time on Feb. 12, 1900, to celebrate Lincoln’s birthday. Booker T. Washington was the special guest that day. Folks have been singing it ever since. One of the things that I love about the Stanton story is that the song was passed on to children from other schools by the school children and teachers who first learned it for that first performance. Indeed, for the first decade, James Weldon Johnson and his brother didn’t try to promote the song. They were busy with other ventures in the early years of the 20th century. But it was passed on by groups of children and teachers who were enthusiastic about its message, even if they surely must have found it to be challenging to sing at first. Just like some of us.

I am always interested to hear what other people’s experiences of singing this song have been. If there is one thing that I would hope that you would take away from my own story, it is that I have a strong conviction that the tradition of teaching people to sing “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” is important for institutions of higher education like UIndy. It is one way to cultivate an ethos that is not only anti-racist but also displays the kind of collegiality that we need to feel we have with one another as we work with students, many of whom struggle to sustain hope for the future when discouraged.

The Witness of Tremayne Horne: Making Space for Black History at UIndy

Can we learn to sing JWJ’s great anthem at the University of Indianapolis? Can it become a vital tradition as one part of our emerging custom of celebrating Juneteenth and other occasions? Can it be one part of a larger effort to make space for Black history on our campus? My answer to these three questions is: Good Lord, I hope so.

Only time will tell, of course. On the one hand, we know that previous generations have had their own encounters with JWJ’s great anthem. We know we are not starting from scratch. On the other hand, we are not doing so well with some of our older traditions of social engagement between faculty, staff, and students. The fact that currently, we find it easier not to gather for university events — in the wake of this awful season of COVID isolation — than to come together to celebrate one another’s lives (and work at the time of retirement) is something that should give us pause. I don’t pretend that celebrating Juneteenth will solve our many problems. I just know that it is a way to engage one of the problems about which we have reason to be seriously concerned.

As Titus Kaphar’s somber statement (see Mission Matters #75) from 2019 should remind us, we have some serious problems here. We should take them one by one with the kind of determined resolve that the lyrics of the second verse of “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” suggest:

“. . . Yet with a steady Beat,

Have not our weary feat,

Come to the Place for which our fathers sighed.”

One of the profound sources of hope, I believe, is our intergenerational connection between the convocation of our predecessors and those of us who have the privilege of being innovators and inventors in the present time. We can learn from the wisdom of the traditions of Black poetry and the Historic Black Church in which the song “Lift Every Voice and Sing” finds an honored place. It is also possible to respect such origins while adding our names to the international company of people who cherish this remarkable anthem.

This the second in a series of five essays I am writing about Making Space for Black History at UIndy. I am calling attention to characteristics of moral witnesses that have taken place on our campus and/or in our predecessor institutions across the years. I have already written about Titus Kaphar, who visited our campus, but is not around to engage today. Still to come are essays about Florabelle Williams Wilson ’49 and others.

Although we have access to words that our predecessors once spoke, we cannot ask them questions. For that very reason, I believe exemplars are best named when they are local and living. We know that they are not perfect; the earthly folks who struggle with daily life just like the rest of us.

That is why I chose to write about Tremayne this month. OK, I suppose his voice does sound pretty close to perfect, but he has to walk across campus like everyone else, and he has to participate in annual evaluations, even if he is the subject of Cartwright’s Mission Matters essay in June.

During the time we have known each other, Tremayne Horne and I have discovered that we share several commonalities. We both went to college in Arkansas (three decades apart!). We both are preachers’ kids. We both are interested in the role the arts play in making social change possible. For Tremayne, who serves on the staff of the Professional Edge Center and is a member of the University’s team of Campus Connectors, it is a matter of practical import as he works every day to mentor college students, many of whom are first-generation college students. What Tremayne does from day to day at UIndy matters. There are many ways he exercises stewardship of the University’s mission, but I would fail to introduce him properly if I did not help you to see the ways that he helps the rest of us make space for Black history.

One of the many things I have come to admire about Tremayne Horne is his fierce pride. You can hear it in his words about the education he received at UofA-Pine Bluff, which is an HBCU. It is evident in his comments about the congregations where he worships and serves. And it is also a factor at play in his loyal criticism of those who are tradition-bound and unwilling to change for the greater good.

Tremayne is also passionate. If you hear him talk about his work with students (at UIndy and as a volunteer youth leader), you will hear his commitment. These things are hard to miss, but what stands out even more is the remarkable hope that he displays, which expresses his faith in the God who has brought him “thus far on the way.” I would like to think that when Tremayne looks at his colleagues at UIndy, he is able to muster hope for the work he does, including the ways he helps us to make space for Black history on this campus. One of the ways we do that is to lend the gift of our presence in celebrating emancipation on Juneteenth.

So, I do hope you will join us on June 17, when UIndy gathers to celebrate Juneteenth. Our Office of Inclusion & Equity colleague, Jolanda Bean, is in charge again this year. Tremayne will lead as we sing “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing.” One difference: the location; we will be gathering for the opening activities in the Murvin Enders Engagement Space on the second floor of the Schwitzer Student Center.

Remember what Tremayne said about the way he was taught to sing this song: “You have to give it the passion that is due to it. You have to be able to sing it fully.” But he and I both know that it takes a while to get there. At UIndy, we are still developing our own traditions of how we will be celebrating freedom – from slavery, for community, with joy and thanksgiving. I assure you. There will be sheets with the lyrics to all three verses of the song that was first written for 500 Black children to sing 122 years ago. In fact, I will be the guy handing out sheets with the lyrics. I won’t be hard to miss.

That brings me to my final point. Please give some thought to what you are going to wear to the occasion. After all, it is a UIndy celebration — of freedom! – in both the personal and social senses. Wear something that displays your own personal embrace of freedom from oppression and freedom for equality.

There are many different ways to celebrate, of course. If you are going to participate in the three-on-three basketball tournament, you will want to wear athletic shoes, or you might wear the Juneteenth t-shirts that Kivonte Johnson designed for last year’s celebration. I won’t speak for Tremayne Horne, but I only wear a tuxedo when there is a marriage, etc. However, I have decided I am going to wear my gold and white paisley bow tie. After all, this is my fiftieth year of learning to sing “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing.”

Come on, colleagues new and old, let’s celebrate together! And don’t you forget, UIndy’s mission matters!