Mission Matters #79: Making Space for Black History: Part V: The Journey Toward Wholeness

This is the fifth and final essay exploring the question of what it means to “make space for Black history” at UIndy that has been part of the UIndy Saga in the 21st Century Project. It concludes the work of the Office of University Mission.

“To think institutionally is to stretch your time horizon backward and forward so that the shadows from both past and future lengthen into the present.”

Hugh Heclo

Today’s reflection marks the end of a body of work — in several senses. This is the final Mission Matters essay I will write, which in turn marks the end of a decade of work in the Office of University Mission.

More significant, I believe, is the fact that the UIndy Saga in the 21st Century Project (2022) has provided our campus community with the opportunity to reach back into the past even as we stretch toward the future.

To invoke Florabelle W. Wilson’s memorable phrase, we have been learning new ways to “tell the whole story.” That begins with listening to our best witnesses, as I have tried to do in the previous four Mission Matters essays. To that same end, a group of faculty, staff and students benefited from the recent visit (Oct. 13, 2022) to campus of Dr. Stanley Warren ’59 (Distinguished Alumnus, 1993) for the first “Lounge and Listen” event — a #BelongSpace opportunity made possible by our friends in the Office of Inclusion and Equity, led by Dr. Amber Smith.

In sum, we are reincorporating stories that have not been told well in the past.

As we have done so, I have been aware of a lurking question: To what extent are we — faculty, staff, administrators, students, alumni, trustees — at UIndy ready to rethink the way we have told our institutional story with respect to Black history? This query is related to the challenging question about social justice that our former colleague Sean Huddleston raised almost five years ago. I have not forgotten his probing question, because the answer that I initially gave in response haunts me still. This last series of essays has been one attempt to provide a more layered reply to that question.

In the final paragraphs of this concluding essay, I will revisit Sean’s question in the context of commenting about prospects for the emergent tradition of celebrating Juneteenth. But the importance of the topic dictates that I telegraph that conclusion.

The journey toward wholeness — in the ways we tell our institutional history as well as in our relationships between one another in the 21st century — requires that we come to grips with the ways that the struggle over the enslavement of African-Americans was part of the earliest effort to create a United Brethren Church college in the state of Indiana.

Let me begin by offering an overview. In the conclusion, I will offer some reflections about the implications of this particular approach for how UIndy faculty and staff might proceed as the University continues to take actions consistent with the Juneteenth Agenda of 2020 put forward by the President’s Cabinet and Provost’s Council.

The beginnings of a United Brethren Church college

Hartsville College (1851-1897) was the first Indiana college founded by the United Brethren. This venture was prompted in part by United Brethren participation in the wider multi-sided anti-slavery crusade that began in the 1830s, led initially by the American Anti-Slavery Society. After the Civil War, the institution continued to be driven by social-reform crusaders, but no longer by the abolition of slavery as such. Then the college closed, and the building burned in a mysterious fire. Several years later, when the United Brethren decided to build a new college, they chose to do so in a different location. By that time, a “Jim Crow” regime made it possible to separate Black and White people — as though such forms of segregation could coexist with the constitutional guarantees of equality.

Indiana Central University was the United Brethren Church’s second attempt to found an institution of higher education. Plessy v. Ferguson (1897) defined the institutional culture of Indiana Central for the first 40 years. Beginning in 1945, however, the leadership of the college reset expectations — in effect re-founded the college — and for the past 75 years, our university has re-engaged the struggles that were present in that initial pioneer institution, where we now know there were students who advocated the abolition of slavery.

UIndy’s history with the abolition of slavery and racism

This is an admittedly odd saga to be re-discovering 120 years into our history, but it is by no means the strangest of stories in American higher education. In the past decade, Harvard and the University of Virginia have had to come to grips with the roles that slavery played in their own founding and early histories. Craig Steven Wilder’s book Ebony & Ivy: Race, Slavery and the Troubled History of American Universities (2013) tells the greater part the story that of the R1 sector (doctoral universities with high research activity). And in case you haven’t been reading The Chronicle of Higher Education lately, more than a few liberal arts colleges — Roanoke College in Virginia and Wingate College in South Carolina come to mind — have had to wrestle with what it means to uphold the ideals of liberal arts education (education for freedom) given that these institutions were built by enslaved Africans.

Our own institutional struggle has a different timeline as well as a different pattern of contradiction and struggle with racism. Even so, I have become convinced that coming to terms with our strange history may be one of the keys to discovering “space for belonging” at UIndy in the richest, most encouraging senses of the phrase.

My task on this occasion has been to gather the most basic elements of the story of the anti-slavery crusade of the United Brethren in Indiana — in particular, the events that led to the creation of Hartsville College, and the student abolitionists’ activism in the early years of that pioneer College, up to the end of the Civil War.*

The origins of abolitionism

The story of abolitionism has multiple origins. Some are transatlantic; others are domestic. Some are religious; others are secular. And some combine both sets of resources. Consider the landmark text: “Declaration on Sentiments of the American Anti-Slavery Convention” (1833).

One cannot fully appreciate this remarkable document without noting the strongly held conviction that the promise of the earlier Declaration of Independence of July 4, 1776, had not yet been fulfilled.

We have met together for the achievement of an enterprise, without which that of our fathers is incomplete; and which, for its magnitude, solemnity, and probable results upon the destiny of the world, as far transcends theirs as moral truth does physical force.

The authors of the Declaration had specific concerns.

That all those laws which are now in force, admitting the right of slavery, are therefore, before God, utterly null and void; being an audacious usurpation of the Divine prerogative, a daring infringement on the law of nature, a base over-throw of the very foundations of the social compact, a complete extinction of all the relations, endearments and obligations of mankind, and a presumptuous transgression of all the holy commandments; and that therefore they ought instantly to be abrogated.

…

We further believe and affirm — that all persons of color, who possess the qualifications which are demanded of others, ought to be admitted forthwith to the enjoyment of the same privileges, and the exercise of the same prerogatives, as others; and that the paths of preferment, of wealth, and of intelligence, should be opened as widely to them as to persons of a white complexion.

Such affirmations angered the wider public, anchored as they were in the denunciation of the already existing compromises, most notably the Fugitive Slave Acts and the Missouri Compromise of 1820. William Lloyd Garrison recalls how the “mobocratic” spirit often confronted the emissaries of the Anti-Slavery Society. A decade later, when three speakers visited Pendleton, Ind., on behalf of the New England Anti-Slavery Society, a mob appeared throwing brickbats. Frederick Douglass was wounded in the process. At one point, Theodore Weld trained a group of 70 (a not-so-subtle parallel to the commissioning of apostles by Jesus of Nazareth) to spread the good news throughout the land. And in a few years, there were more than 250,000 Americans involved in the movement. They were not all of the same mind. Indeed, the movement divided, splintered, and separated in a variety of ways. While newspapers such as The Liberator published by William Lloyd Garrison circulated widely, the movement was decentralized, and the shape anti-slavery took in particular communities could be quite different, some leaning to the gradualist approach, others favoring colonization, etc.

The following paragraph nicely summarizes a complicated chapter in the history of the anti-slavery crusade that culminated in the American Civil War (1861-65).

By 1840 there were 2,000 chapters of the American Anti-Slavery Society throughout the North. However, abolitionists who disagreed with the Garrisonians soon regrouped as a new organization, the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. Other members tried to reform the churches, while others shifted their energies to political antislavery reform. When the government failed to respond to petitioning and lobbying, the Liberty Party was created in 1840 to offer voters a choice in partisan politics. However, the single issue of slavery was not yet strong enough to sway many voters. The new territories gained following the Mexican War led to the organization of the Free Soil Party to block extension of slavery into the new territories. Its strength grew with the passage of the controversial Kansas-Nebraska Act [1854], which repealed the Missouri Compromise’s bar on slavery in western territories north of 36º 30’ latitude.

Britannica: “American Anti-Slavery Society”

We don’t know the whole story at this point. We will never know all of the conversations that took place in small towns and cities of Indiana in the 1840s. In Jennings County, a group of women formed such a society and petitioned the legislature. Others, like the group in Pendleton, hosted the gathering at which Frederick Douglass spoke in 1843.

What we do know is that the “crusade against ignorance” — the quest for universal education — often intersected with the zealous belief that the American promise entailed the abolition of slavery. Although not well-known, that is no less true for us at UIndy.

Hartsville College and the anti-slavery crusade in Indiana: 1847-1851

The story of what happened between 1767, when Philip William Otterbein and Martin Boehm had their famous encounter in Lancaster, Penn., at Long’s Barn (Cartwright, Echoes of the Past in Conversations of the Present, 2003, p. 8), and the formal declaration of anti-slavery advocacy in 1821 is difficult to recover two centuries later, but there are some stories about how participants in the United Brethren movement recognized the inconsistency of living a life transformed by the good news of salvation in Jesus Christ and owning slaves.

That appears to be the case with the family of John Russel (1799-1870), who was involved with the United Brethren movement from its earliest days, when Otterbein began preaching in Baltimore and parts of Maryland. After the young John completed a blacksmithing apprenticeship, his father took steps to set up his son in business. That included the purchase of an enslaved Black man who would be needed to operate the bellows and assist with some of the heavy-duty tasks of that trade.

Instead of going forward with the plan to be a blacksmith, John Russel surrendered to the call to preach the good news of Jesus Christ, and very soon thereafter was serving as a circuit-riding preacher in Maryland, then Pennsylvania and eventually in the Old Northwest. Accordingly, the family emancipated the slave. Releasing the captives became part of Bishop John Russel’s testimony, so it was not uncommon for that topic (and other moral crusades) to be on the agenda when the bishop was present.

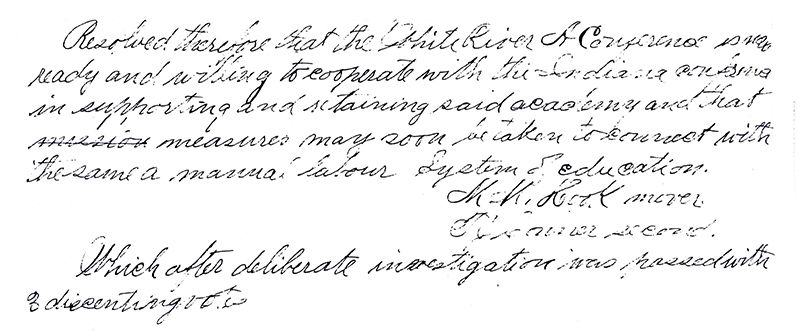

Conversations among United Brethren about launching a college in Indiana began in 1847 when Bishop Russel chaired the session, but the White River Conference of the United Brethren took action on the matter on Jan. 18, 1850. The resolution specified that the college would be based on “the manual labor System of education.” (See the graphic of the handwritten excerpt, below.) Famously associated with Oberlin College, the manual labor focus achieved fullest expression as a proposal in a circular that was disseminated by George Gale in the context of an effort to found a Presbyterian church-related college in Illinois. Knox College provides a nice summary of Gale’s “Prairie College” proposal.

Inspired by the earnest belief in the imminent second coming of Jesus Christ, evangelical advocates of higher education espoused equal opportunity for education for women (sometimes limited to “female courses of study”). In some cases, most notably Oberlin College, this expanded form of liberal arts education included people of color. The story of what happened is messy but not so complicated that it is impossible to draw analogies to other circumstances. See Kornblith and Lasser, Elusive Utopia: The Struggle for Racial Equality in Oberlin, Ohio (2018).

The earliest United Brethren institution of higher education to be founded was Otterbein University (1847), and the founders of that venture self-consciously followed the Oberlin model. Women were included from the beginning, although not in equal numbers to men. Although technically open to Black students, Henry Garst’s early 20th century history of Otterbein University makes it clear that very few African-Americans enrolled in the period before the Civil War and thereafter. In Indiana, given that the Hartsville College founding resolution does not provide a detailed explanation, we cannot know to what extent the declaration that “the manual labor System of education” included specific intentions in this matter. What we can say is that this kind of rhetoric was commonly used in the Midwest by entrepreneurial founders of institutions that were attempting to extend the sphere of literacy beyond the privilege of White males.

We do know that United Brethren leaders like John Russel were very conflicted about what church colleges would mean for the church’s leadership. Would the children of the church grow up to conform to new patterns of urban life? Russel, who was a plain-speaking agrarian who was known for cobbling his own shoes and using his blacksmith skills to shoe his own horses, was known as a crusader who fiercely proclaimed a gospel of “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Righteousness.” Russel was more sympathetic to those ventures in education that were apprenticeship-based, and at one point he explicitly advocated creating a college that would be located on a farm, where students could learn the kinds of skills that would teach them agrarian values.

The United Brethren anti-slavery stance was first articulated in the months after the enactment of the Missouri Compromise. The United Brethren movement spread from the Mid-Atlantic states across the Old Northwest through Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, etc. The Third General Conference of the United Brethren, which was held in Fairfield County, Ohio, in May 1821, formally set forth its rule on slavery:

Resolved and Enacted, That no slavery, in whatever form, may exist, and in no sense of the word shall be permitted or tolerated in our church; and should there be found any persons holding slaves, who are members among us, or make application to become such, then the former cannot remain, and the latter cannot become members of the United Brethren in Christ, unless they monument their slaves as soon as they received directions from the annual conference so to do. Neither shall any member of our church have the right to sell any of the slaves which he or she may not hold.

All of this is important for making sense of the first session of the White River Conference of the United Brethren 175 years ago, on Jan. 18, 1847, in Andersonville, Ind.

Whereas, we believe that slavery is anti-scriptural and unjust, and that the churches connected with and apologizing for that evil are to a great extent its nursery; therefore, Resolved, That we as a conference express ourselves favorable to a connection made by Judge Stephenson in The Watchman of the Valley, to free the different evangelical churches from the principle and practice of slavery.’ (Wilmore, p. 122)

I have not been able to locate more information about the particulars of the initiative in question. The Watchman of the Valley was a newspaper in the Cincinnati area from 1841 to 1849 (first named The Cincinnati Observer in 1840-41 and later briefly named as The Central Watchman in 1849). Initially, it operated under Presbyterian auspices. But what is striking about this resolution is that the focus of action is to combat the spread of pro-slavery advocacy among Protestant congregations in the pioneer era. The terms of contestation were clearly enunciated. The advocates of the crusade against slavery saw the Bible as on the side of justice and slavery was a moral evil not to be tolerated.

Their resolve “to free the different evangelical churches from the principle and practice of slavery” was consistent with the broader movement of evangelical abolitionists who were operating in a decentralized way in the Midwest.

Whether initiated by Bishop Russel or by one of the other participants, we do not know, but I would argue that the fact that this resolution was passed in the context of the initial conversation about launching a church college in collaboration with the community of Hartsville, Ind., is significant enough to warrant reincorporation of the anti-slavery stance of the founders of Hartsville College in our university’s institutional history.

But that is not all!

Consider what else took place at that inaugural session of the White River Conference of the United Brethren in Christ in Indiana. Our primary source for the story is the 1926 History of the White River Conference of the United Brethren Church (hereafter to be abbreviated WRC-UBIC). Augustus Cleland Wilmore (a.k.a. “A.C.”) was a gifted storyteller and appears to have been commissioned to carry out this project as an official approval of a sense of calling to which he had already assented.

“Be it remembered that on Monday the 18th Day of January, A.D. 1847, the members of the White River Conference met in Washington (Green Fork), Wayne County, Indiana. John Russel, Bishop, opened the conference by reading the fourth chapter of the Book of Exodus, from the first to the twenty-third verses inclusive, with appropriate expository remarks which was followed with singing and prayer. In commenting upon the Scripture, which was read by him Bishop Russel entered the sphere of prophecy. In comparing the bondage of the Israelites with American slavery the Bishop declared that as Jehovah had sent Moses to deliver the children of Israel from bondage so God would raise up a champion of liberty who would bring freedom to the bondsmen of this country. . .” (Wilmore, p. 121)

Wilmore was not an eyewitness to the events of 1847, but he had “grown up” in ministry in the WRC-UBIC and he had heard the stories told. He took the minutes for most of the meetings of the conference during the 57-year period that he served. Indeed, the way A. C. Wilmore tells the story of Bishop Russel’s prophetic sermon makes it clear that there is an intricate weave of storied connections between the Black Freedom struggle, the United Brethren Church’s mission in the American Midwest, and the origins of the United Brethren’s efforts to found a church college.

At the heart of these conference actions, of course, lay the movement of evangelical abolitionism (1830-1870).The resolution against slavery pinpointed the problem: Namely, “the churches connected with and apologizing for that evil are to a great extent its nursery.” One way to combat the problem is to provide alternative ways to educate the children and youth of the church. We may never know all the intentions of the conference, but we cannot ignore the fact that the context was defined by a strong set of anti-slavery resolutions and a prophetic sermon against slavery.

Not to be ignored, however, is that at the time the WRC-UBIC began in 1847, the national conflict would not have been the primary focus of the anti-slavery crusade. Rather, as the UB Church’s resolution about the spread of pro-slavery sentiment made clear, Russel et al. were concerned to stem the tide of pro-slavery sentiment within the churches. This was consistent with the United Brethren ethos as a trans-denominational movement that sought to cultivate evangelical fellowship based in a common loyalty to the gospel. Slavery was an obstacle to the spread of the good news. Conversely, to bring an end to slavery was to herald the expected second coming of Jesus Christ.

In other words, their efforts were part of what historians have described as the evangelical abolitionist stream, not the more political agenda associated with the American Anti-Slavery Society led by William Lloyd Garrison and company. Indeed, many anti-slavery advocates in this period chose not to call themselves “abolitionists” due to the activism of Garrison’s allies. And this split combined with other developments to create a political realignment.

Resolved therefore that the White River A[nnual] Conference stands ready and willing to cooperate with the Indiana Conference in supporting and retaining said academy and that measures may soon be taken to connect with the same a manual labor System of education.

M.K. Kook, mover

T.C. Johnson, second

Which after deliberate investigation was passed with 3 dissenting votes.

Student activism and the anti-slavery crusade, 1852-1855

Evangelical abolitionism in the Midwest has multiple origins, but we know that it was often accompanied by student activism. The rebellion of Theodore Weld and the students at Lane Seminary in Cincinnati in the early 1830s is one of the movement’s key moments. When the students’ demand that educational opportunity be given to Black people was denied, Weld & company left to go to Oberlin College, where funding was arranged by Lewis Tappan under the leadership of Asa Mahan. At another point, Theodore Weld trained 70 young adults (mostly men; mostly white) to carry the good news of abolition around the Midwest. We don’t know when the word reached communities of Bartholomew County or the city of Indianapolis, but we know that here and there across Indiana, a few persons and groups were converted to the abolitionist gospel.

Given that the 1850 resolution called for the creation of a college that would be founded on “a manual labor System of education,” we might expect to see evidence of that in the earliest days of Hartsville College, but we do not. There is a good explanation, if we look at what transpired elsewhere. According to the Oberlin College historian, Geoffrey Blodgett, “Little was heard from manual labor as an educational reform at Oberlin after the early 1840s.” Yet so commonsensical was the appeal of this idea to the Pietistic evangelical Protestant settlers in the Midwest — then known as the Old Northwest — that the idea continued to be propagated long after it had already been disproven.

The fact that the idea was still appealing to folks in Indiana who were committed to creating a college in the pioneer era, namely Hartsville College, roughly a decade after it had been proven unworkable is an indicator of stubborn disregard for the facts of the matter. Within a few years, the college had attracted enough interest that there were 88 students enrolled in the College Department (72 males; 16 females) and another 86 boys and girls were enrolled in the graded school. This was enough to show that the venture warranted further investment, and with the expansion of common schools.

By 1859, a pair of students would graduate, and that same year, the college would begin building a large, three-story building. There are plenty of stories about how students at the pioneer college of Bartholomew County taught in various rural schools in the area as a way to support themselves during the years that they were enrolled at Hartsville College, but there are no records to suggest that such a system was ever implemented.

There is much that we do not yet know about the anti-slavery crusade associated with Hartsville College in the 1850s. The primary source for even making the claim about anti-slavery crusade is the 1928 booklet Hartsville College: 1851-1897, written and edited by O.W. Pentzer (Columbus, Ind., 1928), but it turns out that there are several primary sources that make it clear that Pentzer’s booklet is basically accurate.

First documented example of abolitionism at Hartsville College: The first of these is a recollection by a former student and assistant teacher who was asked to recall that period in his life when he was the founder of a short-lived experiment in journalism at the college. In the letter that he wrote from Hastings, Minn., on Dec. 7, 1917, in response to queries about his involvements with journalism in Bartholomew County in the previous century, Mr. L.N. Countryman outlined his experience as editor and publisher of this “monthly, literary scientific, and religious journal” during the 1854-1855 academic year. Named The Western Literary Jewel, Countryman recalled that it had 150 subscribers and published three issues before it closed due to financial difficulties. [MSS 437, labelled #188 in W.W.H.H. Terrell’s historical project.]

Countryman laid out “the published prospectus” for The Western Literary Jewel. It included policy statements about four areas of concern: Religion, Arts & Sciences, Freedom and Temperance. For my purposes, I need to quote only one of them:

“Freedom — we expect to show to the world, feeble as we are, that we are the uncompromising opposers of slavery in all its forms — to show that we intend to work for the emancipation of our country from the withering curse that rests upon her.”

This rhetoric goes beyond the kind of evangelical abolitionist sentiment that we have identified with the 1847 resolutions of the White River Conference of the UBIC. The declared resolve to free the nation from its enslavement to compromising with the slavocracy no doubt reflects the tensions that abolitionists felt in the wake of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which effectively nullified the Missouri Compromise.

In his letter, L.N. Countryman also explained that during this time there was much tension between the people in the community and the students at the college. Indeed, he used the words “hotbed” and “abolitionist” to describe the community, and himself and his peers at Hartsville College in the mid-1850s. Until recently, there has been little else to corroborate this recollection by an alumnus who had relocated to another section of the country after the Civil War and had not continued to be involved with the politics of Bartholomew County, Ind.

Second documented example of abolitionism at Hartsville College

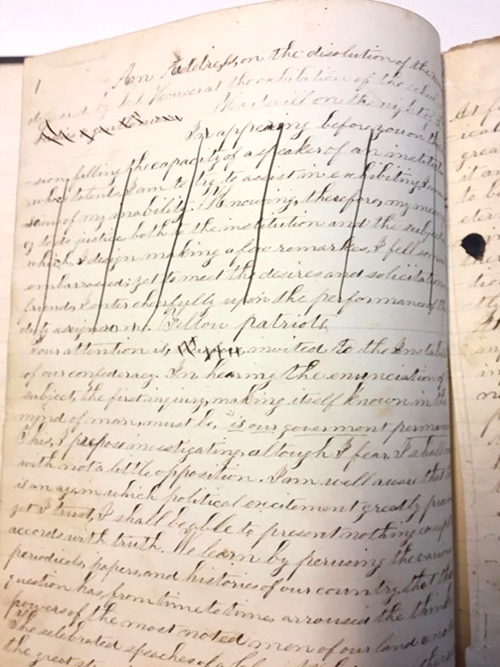

More than a hundred years after Countryman wrote his letter and almost 175 years after the White River Conference voted to proceed with founding Hartsville College, Adam Rediker discovered the manuscript of a “commencement speech” at Hartsville College while cataloguing materials that had been donated to the Bartholomew County Historical Society. Larkin Houser, age 22, gave an abolitionist speech that advocated that the nation should be dissolved rather than tolerate the continual efforts of the proslavery faction in both the south and the north to expand slavery. These are his words: “Where men are permitted to buy and sell human beings, as they do cattle, pure genuine liberty cannot exist.”

Young Larkin Houser spoke with passion about the evils of slavery and saw no reason to hope that the continued expansion to the west would lessen the problem. Indeed, he believed that the inexorable demands of popular sovereignty were such that the United States would have to dissolve. The speech, which was given on April 3, 1855, was the student’s response to the fractious political circumstances of the period after the Compromise of 1850 and the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 that had been championed by Stephen Douglass.

(For the text of Larkin’s address with comments by Michael G. Cartwright, see the forthcoming issue of the Hartsville College Archive Project, Vol. II, No. 1.)

The manuscript of Larkin Houser’s oration was discovered in August 2020 by an archivist at the Bartholomew County Historical Society. It is a rare document in several senses. First, it is the earliest text that we have for the period other than a catalogue from the 1853-54 academic year. Second, it is the only example of a document by a student from that period of the history of Hartsville College. It may be the only example of a student speech in Indiana from that period, but there are examples of speeches like this at Oberlin College in the 1850s. So it would be unwise to treat Larkin’s speech as exceptional.

On the other hand, we should pay attention to the fact that what young Larkin Houser was arguing for on this occasion went well beyond the rhetoric of the 1847 resolution of the White River Conference of the UBIC. Arguably, it also was more radical than the stance of the newspaper with which he may have been involved.

“Political abolitionism” was the most radical form of anti-slavery stance in 1855, and it was enunciated in public at Hartsville College in 1855. We cannot assume that all students at Hartsville College shared this perspective. On the contrary, I think it was quite likely that there were students who were moderates. If they were like most Hoosiers at the time, if they were opposed to slavery, they were more likely to have advocated colonization than they were to have been “immediate” abolition. And to make the matter even more realistic, we should grant Larkin Houser a pedagogical exemption in recognition of the fact that he was still trying to figure out these matters. Certainly, there is evidence in his speech that there were some things that he was a bit confused about, as many other citizens would have been in that year.

What we also know is that this student was not so confused about American politics that he failed to see that the internal contradictions at the heart of the American experiment were on the verge of bursting at the seams. This young man’s speech was burdened by the awareness that the American propositions of Constitutional liberty and individual equality at law were at risk of being nullified. I wonder if he understood that the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which was to govern the conditions under which the territories of Ohio, Indiana, etc. were to become eligible for statehood, specified that slavery was to be illegal. Hoosier assertions of popular sovereignty in the early 19th century attempted to eviscerate that legal precondition. The net effect of the Kansas-Nebraska Act — which incensed Larkin Houser — was to nullify the Northwest Ordinance’s rules against slavery as well as to make it impossible for Black men to be eligible to vote by virtue of owning land, which was the original standard.

That makes it all the more amazing for having been written by a student at the pioneer college of Bartholomew County more than 167 years ago. In my presentations about this incident to classes of UIndy students and public gatherings in Bartholomew County, I have been asked what happened to Larkin Houser. My answer is sad and unsatisfying. He died six months later, and his body was buried in the cemetery of the Baptist Church at Flat Rock, not far from the town of Hope (Find-a-Grave #55422855).[CLF1] [MGC2]

We know nothing about the circumstances of his death. (My UIndy faculty colleague, Dr. Samantha Gray, inquired whether he might have been the victim of vigilante violence. When Samantha said that, I suddenly realized that I had not been thinking with due regard for all of the things that were going on at the time. Part of me wants to caution against speculation. On the other hand, we know that when Frederick Douglass spoke in the year 1843, a decade before, in the town of Pendleton, there was a riot, and Douglass was almost killed. When Harriet Tubman spoke in Northern Indiana in 1861, there was another “mobocratic” disturbance. So perhaps I should say that what is most improbable is the prospect that young Larkin Houser could have spoken as an abolitionist in favor of “disunion” and there would have been no controversy at all.) We simply don’t know what transpired in the period immediately after this speech that called for the dissolution of the United States. However, historians know a good bit about what was happening among members of the anti-slavery movement in Central Indiana that year. As the Indiana historian David Vanderstell explains: “Over 5,000 state delegates attended a Republican Party convention at the State House in July 1855, where they adopted resolutions opposing the extension of slavery and repudiating the Democratic Party.” There are no records available to indicate that Larkin Houser or others representing Hartsville College attended this gathering.

The crusade against slavery: Personal and national

Historians report that abolitionist hopes to end slavery all but died after the 1857 ruling by the U. S. Supreme Court in the Dred Scott case, which determined that persons of color could not be citizens of the United States. This ruling nullified the previous rulings that had suggested that Black people could enjoy the basic civil rights of White people. The civil war that took place in the Kansas Territory the following year (Bleeding Kansas) also appeared to presage a nationwide war between proslavery and antislavery forces.

As the conflict became more nationalized, the abolitionists shifted their stance about the means to be used to continue the struggle. David Vanderstel reports:

As violence increased in Kansas and at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, the majority of abolitionists worked with moderate antislavery Northerners to create the Republican Party (a coalition of Free Soilers, Whigs and Northern Democrats). By 1860 most abolitionists endorsed the election of Abraham Lincoln as a means of battling slavery.

Indeed, all but a few of Lincoln’s fiercest abolitionist critics still identified with the Republican party.

Alumni of Hartsville College remembered how students supported the Republican Party in the 1860 election. In his history, O.W. Pentzer included an anecdote about how the students participated in a Republican parade in the town of Columbus, riding in a wagon decorated to celebrate candidate Abraham Lincoln as “The Rail Splitter.”

Beyond that it is hard to say what evidence he and other members of the Hartsville College Classmates Association may have known to support the contention that the college was distinguished primarily by its advocacy of three moral crusades: against slavery, prohibition of alcohol, and against secret societies.

There is one more brief aside that Pentzer reported at the beginning of his booklet that is quite striking. I quote it here to convey what little we know and how much this one note provokes wonder about what it might mean for the educational experience of students at Hartsville College.

When Professor Shuck came north to take the presidency of Hartsville College, the planter sent along the colored woman who had been the servant of Mrs. Shuck from childhood. [p.3]

Professor Pentzer describes this unnamed woman as having lived in contentment in Hartsville for the rest of her life, but by 1928, her memory had faded. Indeed, no one was still alive who had been a student in 1852 when Shuck first came to Bartholomew County. Due to Indiana state laws put into effect during this period, a freedwoman would have been illegal to reside in Bartholomew County, subject to a fine of up to $500. So the fact there is no census record for this person is not only plausible, but what we would expect to be the case.

More noteworthy still is that in July 1865, the U.S. Census recorded the new residence of Professor Shuck, his wife Josephine and their household. One of the persons listed as living in Lecompton, Kan., is a freedwoman named Mary Latimoor. (I am indebted to Mr. Jean Sneed for turning up this 1865 census record several months ago.)

If Mary Latimoor (1770-1865+) is the same person who was living with the Shucks at Hartsville College, then there is good reason to believe that this provides documentation for what was happening during the 13-year period that President Shuck served as president. Indeed, students at Hartsville College during that period would have known a freedwoman who was born in Virginia before Crispus Attucks died in Boston in 1770. Still to be discovered is when Mary Latimoor was emancipated (presumably in the early 1850s, no later than 1852). She would have been 95 years old when she would have first enjoyed rights as a citizen.

As such, Mary Latimoor probably experienced the promise of freedom long before she first tasted its fruits, but in the 10 decades of her life, which would have included transitions from Virginia to Louisiana to Indiana to Kansas, she would have eventually been freed from slavery and enjoyed a measure of equality, if only as a citizen. We know nothing about her life. We don’t know if she was educated. She may have been a highly accomplished person who was literate, perhaps even multilingual. Or she may have been a person who was unable to read. We know that the Shuck family valued education highly and that other women in the family were tutored as children and educated as adults. So, it is possible that she would have had at least some opportunity to learn. She might also have been an elderly woman for whom life in her 10th decade was a great burden. Both of these things could have been true at the same time.

This sequence is intended to represent the quest to bring her life into focus.

The challenge is to imagine a life like hers. Like students at Hartsville College in the 1850s, we often default to stereotypes. We know that students at Hartsville College would have been reading novels such as Uncle Tom’s Cabin, but if the story about Mary Latimoor is true, then they would have had the direct opportunity to learn about what an actual person had experienced as enslaved. Not to put too fine a point on the matter, but the presence of a recently emancipated Black woman at the college — as a member of the president’s household — could have personalized the matter in a way that would have been difficult for students like Larkin Houser to ignore.

We are talking about that mysterious phenomenon by which the moral imaginations of ordinary people are changed. We know from the contemporary struggle of LGBTQIA+ students, faculty, and staff at UIndy that actually knowing someone who identifies as gay or queer often changes the way that we think about the matter. And we also know that this kind of thing also was happening in the 1850s in places like Indiana, Ohio and Kentucky — and in particular at Hartsville College. All of which means that we confront the challenge to imagine something that is beyond the range of our own experience.

As the recent historical novel entitled Horse by the Australian-American writer Geraldine Brooks illustrates, a person who was enslaved might still have been highly accomplished. In her review for the New York Times, the writer Alexandra Jacobs describes the novel as about “the power and pain of words,” and it most surely displays both aspects, which we associate with the gift of literacy. Part of why that can be the case is because of the juxtaposition of the present and the past, which exhibits the continuity of social injustice across time.

Jacobs summarizes the inception of the plot:

The book opens with Theo, a Ph.D. candidate in art history at Georgetown who pulls a painting of Lexington out of a hostile neighbor’s trash in 2019. In short order, the action zooms back to 1850 and Jarret, a skilled groom whose enslaved father had bought his own freedom but couldn’t afford his son’s.

From this baseline, Brooks has crafted a marvelous fictional account that has an intricately woven historical basis. In summary, it displays how it is that things that happen in the present are intricately and irrevocably connect to the past.

Geraldine Brooks brings the character of Jarret alive in ways that go well beyond social stereotypes that many of us still carry when we think of slavery. She describes him in the different contexts of enslavement — to different “owners” — and how Jarret developed the capacity to adapt, to survive the threats to his existence and ultimately purchase his freedom. In time, he thrived. And what was the key to Jarrett’s life-story? In one sense it was learning to read. In another, it was his relationship to a horse, for which he cared. And at the same time, the novel presents the deep pain that surrounds the life of the character of Theo, who despite his intellectual precocity, athletic prowess, and international sophistication, nevertheless loses his life, due to the prevailing existence of systemic racism that ultimately reduces him to being a Black man who is imagined to be a lethal threat to a White woman and who dies an unnecessary death.

This modern novel provides context for what could have been Mary Latimoor’s experience.

Mary Latimoor lived in four different sections of the country during her lifetime. The circumstances of slavery in Virginia and Louisiana could have been quite different, while being quite oppressive, even if the circumstances of life at Hartsville College and Lane University are likely to have been roughly comparable to one another, due to the fact that both were fledgling ventures in higher education, still very much under construction. Who can tell her story? Not me. And yet, we dare not forget her story if we want to engage the narrative of Hartsville College. Some would say that we would be better off not trying to do so. I disagree.

Making sense of our history of student abolitionist activists

What can we conclude from these few facts and pair of documents? First, we cannot say that Hartsville College was an abolitionist institution in the sense that Union Literary Institute in Randolph County (founded in 1846) or the Eleutherian Institute in Jefferson County (founded in 1848) were, but we can say something that cannot be said about either of those institutions: Namely, Hartsville College was an institution of higher education where there were students who were abolitionist activists during their college years in ways that were similar to the student activists who founded Oberlin College in 1833. Except in this case, the students at Hartsville College do not appear to be “evangelical abolitionists” like Theodore Weld & company.

Those we know about would have shared the temperance witness that was widely shared by many abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass, but their focus was not on the need to “emancipate the churches” (as was the case in 1847 when Bishop Russel preached his sermon) as it was to liberate the nation of the United States of America from its multiple forms of compromise with the evils of slavocracy. In sum: The students we know about — L. N. Countryman and Larkin Houser — were political abolitionists. And circumstantial evidence suggests that students of their generation would have known a person who had been enslaved in Louisiana and lived in the household of the President of Hartsville College from 1852 to 1865.

How much more there is to the story of Hartsville College student activists advocating abolition of slavery, we cannot say. However, we know that the United Brethren witness against slavery did not continue after the Civil War. Freedom from slavery did not result in equality of status or opportunity. And the government’s plans for Reconstruction were not realized. The Compromise of 1876 led to the renewed practices of what would become more institutionalized practices of racism. We also know that the experience of the Civil War shifted the way the history of abolitionism came to be told. In the wake of his death, which came in close proximity to Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Abraham Lincoln became the Great Emancipator, and his life was enclothed with imagery of sacrifice; he became a Christ figure. This is also true of the way United Brethren church leaders told the story about the evangelical abolitionist witness of people like Bishop John Russel. In fact, it is possible that the specifics of the 1847 event noted above were recalled in such a way as to contribute to premature closure of the prophetic witness against slavery.

Consider how Rev. A.C. Wilmore told “the rest of the story” about this occasion that took place on Jan. 18, 1847.

Nearly sixteen years passed [i.e. 1863] before the fulfillment of the Bishop’s prophecy. Strange to say but thousands of our national heroes sacrificed their lives on the altar of Antietam, near the Bishop’s home, before his prophecy was fulfilled by the great emancipator, Abraham Lincoln. (Wilmore, p. 121)

This prophecy-fulfillment schema is too neat, given that people of color continued to suffer and endured great oppression.

[Wilmore’s life is another case study in how a person can shift from being a social radical before 1885, to being a moderate during the last decade of the 19th century, to taking stances as a social conservative in the first quarter of the 20th century. The fact that this same person was the namesake of a dormitory at Indiana Central College in the period after World War II is an odd indicator of the strange moral legacy that UIndy bears in matters of social justice.]

This way of telling the story of the United Brethren crusade against slavery is disturbing, but precisely because of the stories that we have about what happened at the first session of the White River Conference, we have a basis for seeing how the story shifted during that period. In 1847, John Russel denounced the practice of slavery and led the conference in a conversation about the effects of pro-slavery sentiment on Protestant Churches such as the United Brethren. After 1863, Bishop John Russel would be remembered for the fact that his 14-room home had been turned into a hospital where Union soldiers were cared for during and after the bloody Battle of Antietam (summer of 1862). The North ultimately won that battle, a victory that made it possible for Lincoln to announce the Emancipation Proclamation.

These are the kinds of archival discoveries that are both fascinating and frustrating for someone who is interested in institutional history of higher education. How could it be that no one at the University of Indianapolis knows these things in the 21st century? If this history was known to the founders of Indiana Central University, why would they ignore it? I suspect that these queries are misplaced. Memories shift across time, and what one generation remembers in one context, another may recall with a different emphasis.

Regardless, enough evidence of the anti-slavery crusade at Hartsville College exists at present to recognize that there is a legacy to be engaged.

The challenge that lies before us is to discern how best to do this for the good of the institution as a whole. That is a conundrum that is deeply personal and at the same time institutionally quite fraught. As I explain in the podcast on “Social Reform Matters” — #12 in the UINDY@120 series — even if we disagree about whether UIndy has a tradition of social justice, we need to pay greater attention to the ways that moral crusades such as prohibition and anti-secret societies captured the attention of our predecessors to the exclusion of concern about racial injustice in Indiana and beyond.

The question of social justice, revisited

Questions come to us from multiple sources, such as from archives of texts and census records that help us understand the lives of Larkin Houser and Mary Latimoor, two people who may have known each other across the color line at Hartsville College during 1854-55 academic year. Other queries are articulated by colleagues, such as Sean Huddleston’s forthright question, which he voiced in the context of the University Planning Commission (UPC) at UIndy just a few years ago: Does the University stand for social justice?

At the time that he posed the question, President Rob Manuel redirected the concern to members of the UPC. “Does the University have a tradition of social justice?” he wondered. On that occasion, I responded by saying: “Based on my knowledge of the University’s history [meaning since 1902], I am not aware of a tradition of social justice. There are a few relevant exceptions, but . . .” [One-off exceptions included the student protests that occurred when President Sease announced that Daily Hall was to be razed in 1984 and the effort by several faculty and a few students to get the University to divest from South Africa in the 1990s.] I went on to say, “If we look at it in the context of the church affiliation, the United Methodist Church does have such a tradition, albeit a conflicted one, but that doesn’t seem to have influenced what was happening at the university across the years.”

At the time, I was uncomfortably aware of the fact that my answer was incomplete, but it has taken me a while to do the research (about what transpired at Hartsville College in the 1850s and in the United Brethren Church after 1821) to discover just how much that is the case.

It is not that our predecessors have never confronted questions of social justice across the past 175 years. But — so far — our institutional memory has not stretched to encompass the past and the future (as Hugh Heclo advocates) in such a way as to call forth the moral resources we need to address the question effectively.

I am quite sure that Sean Huddleston was not the first person to wonder about whether the University can take a stand for social justice. I know of faculty — Robert McCauley and Charlotte Templin in the early 1980s, Terry Kent and Kate Ratliff in the 1990s — who have dared to ask uncomfortable questions and state inconvenient truths about where the University stands. There is always a potential question about injustice. And where it is carried over from the past, there is the potential for an unfolding tradition of social justices. Bishop John Russel’s sermon in 1847 reiterated the United Brethren Church’s stance publicly affirmed over 200 years ago in 1821. We continue to hear its echo 175 years after those United Brethren who first imagined the creation of Hartsville College, who did so while also restating their opposition to slavery and denouncing the churches whose Christian witness was corrupting the witness to the Gospel.

As we come to the end of the year 2022 at the University of Indianapolis, the faculty and staff of the University are struggling to find institutional stability amid diverse patterns of personal struggle, even burnout. We long for wholeness, we are not sure which direction to take, and we are looking for leadership. Students, alumni, trustees and friends of the university may articulate their interests, concerns, and aspirations in different vocabularies, but they too have deep longings. To invoke the title of Wendell Berry’s recent book, we are grappling with The Need to be Whole.

In the midst of the multiple forms of malaise we are experiencing in the year 2022, there are the haunting questions of racial injustice and prejudice that stem from what Mr. Berry once described with understated eloquence in his remarkably astute book The Hidden Wound. A recent article by Joshua Hochschild in Local Culture explicates Berry’s decades-long exploration of this conundrum: “The stories we tell about our wounds, and about how to heal from them, are themselves part of the process of healing. Americans need a story that offers the possibility of authentic wholeness.” There is truth in Hochschild’s observation. And given the history I have sketched above, these questions are especially pressing at the University of Indianapolis.

That is where I believe we need to re-engage Sean Huddleston’s question about social justice. To date, our university’s institutional histories have not explored these connections, in part because they have not been well known and/or understood. But that does not mean that they have been totally unknown. Rather, those who have told the stories have tended to set aside the narratives of the predecessors, and that is what I have come to believe must be challenged. When we do this, we discover that there actually is “Black history” to be discovered within the saga of the university. And that means that there is the possibility that folks at UIndy might yet develop a tradition of social justice.

I am also aware that my four preceding essays on “making space for Black history” can be read to suggest that exploring Black history is about discovering something that lies “outside” the timeline of the history of the institutional history of the University and its predecessors, Indiana Central University and Hartsville College. That is not the case for the saga of the United Brethren Church’s efforts to found a church college at Hartsville and later in University Heights. Indeed, the quest for racial equality and resistance against the enslavement of Black people can be found at the very beginning of the story of how we came to be as an institution founded by the United Brethren in Christ.

We are only beginning to understand the ways that “the three foundings” of the University have intersected with matters of race. We have a complicated inheritance, to be sure. And truth be told, some of us have been ambivalent about whether we are ready to encounter the moral legacy of abolitionism for the citizens of Indiana, not to mention those of us who are heirs to the heritage of Hartsville College, which was founded by antislavery crusaders. The end of the story has not been written. We may yet discover ways to reincorporate the stories of Black history into the UIndy saga alongside the remarkable creativity of selected faculty, staff, and students, some of which happen to be people of color.

Indeed, it has already started to happen. Look around you. The annual celebration of Juneteenth at the beginning of the summer, the Ode to Blackness Art Exhibit earlier this fall, the Diverse Expressions Fashion Show in early December — these are some of the more noteworthy and inventive opportunities that UIndy’s Office of Inclusion & Equity have made possible. These things are taking place on campus because of colleagues such as Dr. Amber Smith, Jolanda Bean, CariAnn Freed ’21 and current UIndy students like Primrose Paul ’23 and Kivonte Houston ’23.

There are more ways to connect with the past than we have dared to try thus far. And I expect to hear about what happens in the future. Thanks for taking the time to read this and other essays I have written. It has been a privilege to do this work. And now, I pass the scribe’s pen to those who will share the work of mission stewardship in 2023.

— MGC

*Please Note: I invite those who want to learn more about what might be called the “prologue to the story” of Indiana Central University to join me as I continue — in retirement — to work through these issues in greater detail in the Hartsville College Archive Project. The forthcoming Volume II will provide more detailed accounts of these matters that build upon the materials in Volume I, which was dedicated to the leadership of the Hartsville College Classmates Association. If you are interested in receiving updates, e-mail Michael.G.Cartwright@gmail.com. I will put your name on the email distribution list for 2023.