Mission Matters #78: Making Space for Black History: Part IV: The Witness of Dr. Stanley Warren

by Dr. Michael G. Cartwright, vice president for University Mission

This is the fourth of five essays about what it means to make space for Black history at the University of Indianapolis and its predecessor institutions. In each case, one or more people will be the focus of discussion. As much as possible, I will use their own words to talk about the particularities of their respective witnesses.

In the three previous essays in this series, I have explored three different patterns of making space for Black history. I began with the visit of Titus Kaphar to our campus in 2019 (MM #75), when many of us were grateful to be challenged to take the measure of works of art that reframe scenes of the past in the midst of social conflicts of that remain in present. In the second piece (MM#76), I called attention to the work of our UIndy colleague Tremayne Horne, who serves on the staff of the Stephen F. Fry Professional Edge Center, in addition to performing operatic works and leading folks at UIndy in singing “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing.”

In the most recent essay (MM #77), I profiled the life and work of Florabelle W. Wilson (FWW), who curated several exhibits, beginning with “Invisible Sinew,” about the oral histories of Black families on the southside of Indianapolis. Held in 1980, this was the first in a series of exhibitions and educational storytelling that FWW made possible while she served as academic librarian. In the conclusion of that essay, I called attention to the recently curated exhibit by Primrose Paul ’23 (Studio Art), “Ode to Blackness,” which serves as a reminder of challenges yet to be explored and the treasures still to be found when it comes to engaging the lives of Black people past, present and future.

The UIndy Saga in the 21st Century Project (2022-2024) provides the context for my exploration of a fourth example in this month’s issue of Mission Matters. With funding from the Council of Independent Colleges, this project’s purpose encourages UIndy employees to tell their stories about what it means to serve as faculty and staff at the University. The leaders of the project are excited about the ways students like Primrose Paul have already launched convergent initiatives. The UIndy Saga Project also provides our campus community with the opportunity to reach back into the past to tell the stories of alumni whose accomplishments have not been well-told, even if they have been recognized at some point in the past. The FWW retrospective is one good way to carry out that mandate in circumstances where the subject is no longer alive.

Another approach is to collect oral histories of living witnesses to history alongside samples of their lifework and thereby begin to reincorporate stories that have not been in focus in previous narratives of the past. Let me illustrate what difference this makes, and then I will say more about Dr. Stanley Warren’s impressive life and career as an educator in both high school and university settings.

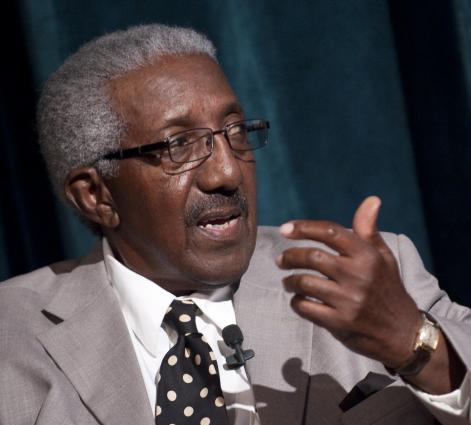

I am very grateful to be able to share with my UIndy colleagues Dr. Warren’s reflections from earlier this spring when he visited campus on April 28 for an oral-history interview. He is one of those rare souls who, by virtue of his life experiences, can serve as both a living witness and an authoritative guide to take people with questions into spaces that we do not know as well as we could.

Part of what we can learn through conversations about Stanley Warren’s life and work is that the question of making space for Black history at UIndy involves going beyond the categories and frameworks we already are using to begin engaging what we don’t know or haven’t even realized was on the map for exploration. Having learned, with Dr. Warren, what we didn’t know that we didn’t know, we are better able to reincorporate knowledge of our past – individual and collective, personal and institutional –with the new perspectives that we have developed through our interaction with living witnesses.

Stanley Warren as participant-observer on the varsity basketball team at Crispus Attucks High School during the 1950-51 academic year

I met Dr. Warren in the parking lot shortly before noon on that day in late April, as we had agreed. We walked past the bell tower and through Schwitzer Student Center. I had arranged for lunch to be served in the President’s Dining Room, a space I had not entered since February 2020 (i.e., before COVID). We began visiting and I explained the arrangement that I had made for recording the oral-history interview. I was trying to be very careful. I didn’t want to rush our guest, and I also didn’t want to get ahead of myself. We would have lunch, and then we would shift to recording the oral history. I had prepared well. The night before, I had re-read Dr. Warren’s history of Crispus Attucks High School so that I had some basic facts in mind, and I also made notes about the few photos and activities reported in The Oracle yearbooks from 1958 and 1959.

My colleague, Janel Bogenschutz, associate vice president of advancement, arrived shortly, and the food was being served when Stanley Warren began talking about what it was like to be a high school student in the late 1940s and early 1950s at Crispus Attucks High School. I think I had just taken a bite out of the baked potato on my plate when I realized what Dr. Warren had just said: “I was on the basketball team — just as a member, not very good. . . . I knew that one of the reasons I was on the team was because of my academics. I was a good student; they knew that I wasn’t going to flunk off the team. Coach Crowe knew I would always be eligible; they didn’t have to worry about checking my grades at the end of the six-week period, and so on. . . .”

Suddenly, things clicked in my brain as I registered what he was saying. I interrupted our guest’s story and said, “Excuse me [I hope I started this way], Stanley, did you just say that you were a member of the 1950-51 basketball team at Crispus Attucks?” He said, “Yes, that’s what I said. I didn’t dress for the tournament games, but I was there and heard what Coach said to the players during the game.” At that point, my eyes got really big. I looked over at Janel. She grinned. She could tell that I was excited. As I recall, I said something less than eloquent — like “Wow!”

I had forgotten that I was supposed to be hosting a conversation with a distinguished alumnus. The basketball fan in me began to compete with the would-be cultural historian and institutional story-collector. I couldn’t believe that I was talking with someone who had been a participant-observer in one of the storied athletic contests in Indiana high school basketball history. It did occur to me that I should at the very least explain to Janel (in case she didn’t know) why it is important enough for me to interrupt our guest the way I had done.

I stopped and said, “As you know, that is a game that historians have written quite a bit about.” I dropped a few names (Richard Pierce), and I alluded to Ted Green’s fine documentary film. “So, Stanley, if you don’t mind me asking: as someone who actually witnessed the game – from your spot sitting on the bench — what do you make of what these folks say about how Coach Crowe was so aware of the politics of the matter that he made the guys on the team self-conscious about the prospect that they would win, and you weren’t playing loose like you needed to play in order to win the game? They say that the anxiety about the social consequences of a Black team winning the championship could have cost the Crispus Attucks players the game.”

Dr. Warren looked at me with his eyes dancing with merriment and gave a one-word response to my question: “OVERBLOWN!”

Then he started to get a bit excited, too. He explained some of the things that the historians had missed. Ray Crowe was “a rookie coach. He didn’t have any experience playing in big games like that.” The 1950-51 team was Ray Crowe’s first year to coach any sport.” Stanley stopped, put his napkin down, and grinned. “Look, Michael, Coach Crowe was really on the guys during time-outs and at the break between periods, saying things like, ‘Look, guys, you have elbows. Use them! You’ve got to start boxing them out of the lane!” Stanley paused for a second and grinned at me. “So you see, Michael, Coach Crowe was there to win that game.”

Apparently, Stanley was sufficiently impressed that I knew my basketball history as well as something of the history of Crispus Attucks. He rewarded me by sharing his perspective on the matter:

He was a rookie coach. He was doing this for the first time. His inexperience showed. Now, as for the principal of the high school, Russell Lane, that’s another story. He was certainly anxious about public perceptions. … I think Ted Green got that part right. … So we lost that game. But the experience helped Ray Crowe become a better coach, and when his teams played for the IHSAA state basketball championship again in 1955 and 1956, the Crispus Attucks Tigers teams won.

Thanks to Stanley’s vivid description, I began to see the events of the 1951 basketball game in a new way: The intense atmosphere of the game … a close score … two competitive teams in the final game of the state tournament. For those who don’t know that bit of Indiana history, I recommend that you take a few minutes to watch part of Ted Green’s documentary. It is one of the greatest moments in Indiana high school basketball history, and I cannot believe that I had the privilege to hear Stan Warren talk about what it was like to be playing for the Crispus Attucks Tigers team 71 years ago.

There is more to the story, of course.

The story of what the teenage Stanley Warren experienced in March 1951 when he played for the Crispus Attucks Tigers basketball team is an extraordinarily vivid example of what can be learned from a living witness who participated in significant moments of cultural transition. Stanley Warren is also one of the best guides to the history of Black institutions in the city of Indianapolis, having written 19 articles and three books over the past three decades, since retiring from his career as an educator in both secondary and post-secondary contexts.

During our lunchtime conversation, we took a few minutes to look at a couple of the books that Stanley Warren published. Stanley Warren was curious about the fact the Krannert Memorial Library copy of one book, Crispus Attucks High School: Hail to the Green, Hail to the Gold, a 1998 commemorative history of Crispus Attucks High School that was sold to benefit the Indianapolis Public Schools Crispus Attucks Museum, is bound in green. Once upon a time, there were only two copies of the book in that binding. Stanley Warren owns one. The other was owned by fellow Indiana Central College alumnus, Gilbert Taylor ‘58, who served as the first curator of the museum. Stanley and I speculated that perhaps Gilbert donated his copy to the University as a bequest following his death a decade ago. Otherwise, it appears that there is a third copy of the rare book. Copies of similar rare books have been known to sell for hundreds of dollars – if and when they are available — on eBay or other e-commerce outlets or in local bookstores.

I was already very familiar with this book before I met Stanley Warren. I had spent some time reviewing it before our lunch meeting because I wanted to make sure that I had the basic details fresh in mind. While keeping only the most relevant details in view, Stanley orients readers to the history of the creation of a segregated high school in Indianapolis. The dedication of the new high school on October 28, 1927, was part of the “desire of a large segment of the White population to create separate facilities in all walks of life.” What transpired in Indianapolis set the stage for the other urban centers of Indiana.

He also provides guidance for readers who do not have the background for understanding features such as the acts of the General Assembly (1869 and 1877) that specified the limited provisions for the education of Black children and youth, both of which constituted the first steps, however limited, away from the Negrophobia of 1831 and 1851 (see Article XIII of the Indiana State Constitution) that prohibited Black immigrants from entering the state. Even so, during the four decades between 1860 and 1900, the Black population of Indiana increased from less than 500 to almost 16,000 people.

The chapters of the book describe the different programs and activities of the school. The triumphs of the famous basketball teams in the 1950s are well explained. Warren helps readers who are unfamiliar with the history of court-ordered desegregation in Indianapolis to understand what unfolded in the 1980s that ultimately led to closing the high school and subsequently re-opening it as a junior high school.

The story he tells about the high school from which he graduated in 1951, and where he taught for a decade in the 1960s, includes both moments of triumph and chapters of trauma that have had lasting effects. At the end of the book, readers come away with a strong sense of the reasons for the fierce pride of alumni — and the deep grief associated with the origins of Crispus Attucks as a segregated institution — as well as the deep sense of loss when, as segregation came to an end, the community of learning that existed for almost 60 years ceased to be.

I am pleased to report that the day I interviewed Stanley Warren in late April 2022, I also learned much that I did not know about the history of this University. If you would like to know what I found out, view the Stanley Warren exhibit on the UIndy Saga in the 21st Century Project website.

The witness of Dr. Stanley Warren’s life and work

In retrospect, Stanley Warren’s life and work straddle the era of Jim Crow (when the regime of racial segregation was enforced by law as well as custom) and the partial integration of institutions of higher education (which began in the mid-20th century). The struggle continues in the 21st century, as we are now confronting the effects of the “New Jim Crow,” which is now so intricately entangled with immigrants, and/or incarcerated Black and indigenous peoples.

The book about Crispus Attucks High School is deeply poignant, combining recognition of both the losses as well as the gains that have accrued from the integration of public schools in Indianapolis. In the closing paragraphs (page 156) of Hail to the Green, Hail to the Gold, Stanley Warren voices the doubts of alumni about the likelihood that junior high school-age youth can develop a “deep appreciation for the great heritage laid before them.” He nevertheless affirms the hope that “someday, when their vision is clear and they look back over the stony road, they too will sing of Crispus Attucks High School in rich, resonant tones.”

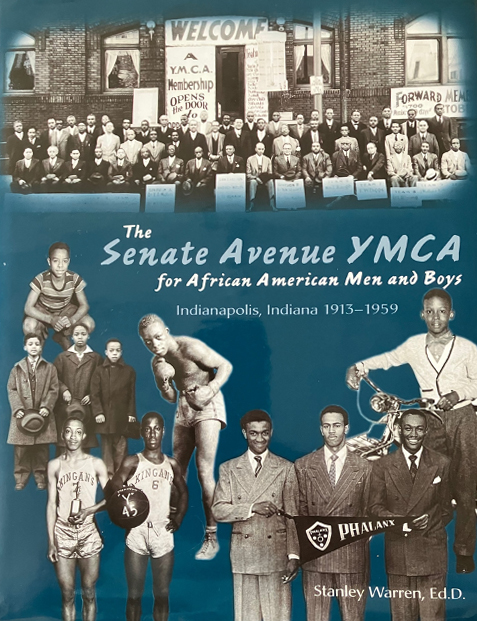

Another book Stanley Warren wrote, this one about the Senate Avenue YMCA, is poignant both because it tells the story of what success looked like during the struggle against segregation, and because it details the painful losses that came about after 1959 under a different set of conditions. In the opening sentence, Stanley Warren testifies to his experience of writing the history of a predominantly Black institution: “Writing history is sometimes a daunting process beset by vagaries, intimidation, and hours staring at blank pages. As intimidating as the process is, the beauty of discovery makes the work worthwhile.”

I resonate with that frank yet hopeful testimony. I have found those sentiments to be especially true in my attempts to write about the witnesses of those people who “make space for Black history” at this University. Stanley Warren understands the challenges associated with using words to convey the experiences of those whose lives have been framed by racism but who have also found ways to succeed even when the frameworks distort the integrity of the way they have lived their lives.

I regard it as a privilege to have interviewed Stanley Warren for the UIndy Saga in the 21st Century Project. I came away from that conversation with several strong impressions about the remarkable witness that he has offered in his life and work.

The first is his persistence in recounting the history he has witnessed across the years (1932 to the present), as well as the history that reaches back through the four centuries of Black history in North America before he was born. As a high school student, he was present for one of the most storied basketball games in the history of IHSAA (Indiana High School Athletic Association) sports. During the years that he taught at DePauw University, opportunities for advancement required that he focus his academic endeavors on pragmatic goals, but teaching Black history was always central to his own academic purpose. He developed his own habits of writing and scholarship. He educated undergraduates at Depauw, where he discovered that many White students were eager to learn about Black history. And in retirement, his writing has preserved the record of historic Black institutions of the city of Indianapolis for the benefit of people of all races.

Second, his resolute commitment to truthfulness is also remarkable. As he has stated succinctly with just a touch of humor, “People think I make up stories; but I don’t.” He was not encouraged by the faculty at Crispus Attucks to go to college. At the time he was a student (1948-1951), the goal was to graduate from high school. His education at Indiana Central College certainly was important to him, but what transpired during those years was not transformative for him in the way that other experiences of his life have turned out to be. Before he enrolled in college, he learned the art of fair play in the pool hall. Being a student at ICC was not a season free of racial prejudice. As a commuter student, he took little part in campus life. He did his work for classes, and then he left campus – like most other Black students of that era. He ultimately found mentors elsewhere, such as Dr. Joe Taylor at Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI), who encouraged him to get a doctorate and who helped him make his way into the world of higher education. This is no less true of his testimony about matters of the public record. He is unapologetic about his criticisms of the politicians who created UNIGOV. He is also resolute in testifying to what he experienced, even when the stories he tells are disconcerting to those who would like to think that his experiences were the exception to the rule.

Third, Stanley Warren is both an authoritative interpreter and guardian of the history of the Black communities of Indianapolis. He is a living witness. He has consulted with other scholars (such as activist-historian-writer David Leander Williams) and a filmmaker (Ted Green) who have recounted the story in their own media. Indeed, he is one of the writers who has helped to clarify the differences between various personalities (e.g., Andrew Ramsey, Russell Lane and Ray Crowe) and factions in the history of Crispus Attucks and the ways such oppositions emerged in response to the changes brought about the Supreme Court rulings, etc.

And there are more than a few people who count him as both a teacher and mentor. These include the late Wilma Gibbs-Moore, who was one of the students who participated in the Indiana Central College Black History Club in the 1960s and went on to serve with distinction as the curator of Black History for the Indiana Historical Society.

Finally, Stanley Warren’s self-knowledge as a living witness is also quite remarkable. There are matters of his personal history (as he described in the web exhibit) that he has come to see from the vantage point of more than nine decades of self-reflection. Some aspects of his life are mysteries. He can imagine how his life might have been different than it was, but he also accepts the person he ultimately became and how he responded to the challenges he encountered over the course of his lifetime. He knows himself well enough to believe that if the administration of IPS had not transferred him from Crispus Attucks High School, he might never have left the old school located at the western edge of the old Indiana Avenue business district. Knowing that might well have been the case is poignant. Knowing that the course of his life was changed in ways that made it more likely that he would be one of the few people who were well-positioned to tell the story of Crispus Attucks High School, he ultimately takes on the challenge of telling that story. It turns out to be the contribution for which he has been best known.

Stanley Warren’s sense of stewardship of the stories of the past, like that of Florabelle Williams Wilson, is uncommonly strong. In Stanley Warren’s case, though, he has gone beyond the tasks of curation. He has written the stories in ways that have made it possible for others to curate, and he has taken steps to ensure that the archival record is as complete as possible. He is a living witness who was already recognized by his alma mater for distinction three decades ago (1993). That was before he wrote three books and 19 articles about Black history in Indianapolis.

We now have the opportunity to recognize to Stanley Warren as an elder, in the sense of being a wise educator who has much to teach us, given all that he has learned during his sojourn as student at Crispus Attucks High School (1948-1951) and Indiana Central College (1955-1959); faculty member at Crispus Attucks (1960-1970), Howe High School (1970-71) and Depauw University (1974-1992); and author of three books of Black history (1998-2014).

Please join the Office of Inclusion and Equity, the School of Education and the Office of University Mission as we host Dr. Stanley Warren for a visit to campus on Thursday, October 13. Watch your email for an announcement as the date approaches.

Remember, UIndy’s mission matters!