Mission Matters #69 – Temperance Lost from 1923 to 1945

By Michael G. Cartwright, Vice President for University Mission and Associate Professor of Philosophy & Religion

This year we are exploring marks of excellence that can be discerned in the past and present of our institution. Virtues are displayed in the context of practices and social relationships, they reflect moral traditions, they are embodied by exemplars, and they are sustained by institutions such as universities. In MM #66-68, the focus was on the virtue of temperance. In this issue, I explore what happened when the temperance tradition was lost and a new set of social mores came into existence around the sale and consumption of alcohol. Consider the seven “exhibits” that illustrate this shift.

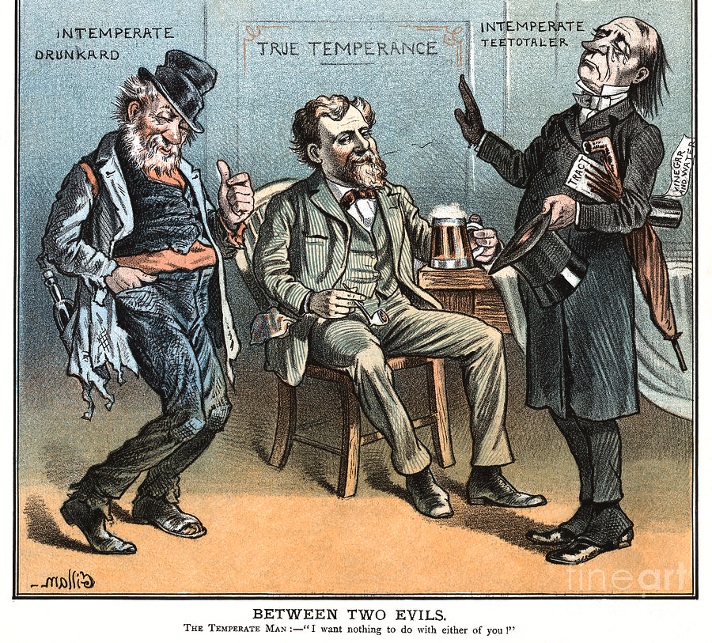

Humor is a very useful index in understanding institutions, traditions, and practices – especially where social change has mixed results, which may entail perceived losses as well as hoped-for gains. Political satirists – on all sides of the debate — had a lot of fun lampooning participants in the culture wars over temperance. Consider Bernhard Gillam’s wonderful “Between Two Evils” cartoon published in Puck’s Magazine in 1882.

This particular cartoon displays the social conflict at a moment in the struggle between advocates of temperance when moderates were pushing back against factions of Teetotalists and both were attempting to combat the social evils created by the Saloons, establishments where men young and old went to drink often to excess. The emerging split (among men) Temperance movement was between the Prohibition Party, which was trying to drive a wedge between the two national parties, and the Murphy Movement, which was trying to revive the antebellum culture of “moral suasion.” The figure of the sodden drunkard had been around for a long long time in American popular culture – think of Huck Finn’s Pap – but the caricature of the Temperance preacher was still developing. And “Between Two Evils” offers a wonderful depiction of the Teetotaler that displays why some Americans past and present would be repelled by the Dry stance.

In this case, the figure of the Teetotaler has his signature temperance tract or pamphlet, has his hand raised offering a pious admonition, and is carrying a bottle of vinegar and water (a temperance drink) under his arm along with an umbrella (to keep from getting wet – get it?). I am not sure if the hat is being held out asking for contributions or not, but this association would have added to the image of the “intemperate man,” a figure of deficiency in the sense that he doesn’t have an imagination for the right use of alcohol. At this point, the vague notion of “responsible drinking” was ill-defined in a dichotomy produced by Teetotalism. So part of the satire of the cartoon was that the debate became so skewed by conflict that even someone who drinks only beer (or wine) looks like a hypocrite although selective abstinence was an earlier pattern of temperance.

Gillam’s 1882 cartoon offers a limited illustration of this problem of moral perception. Both the drunkard and the teetotaler are intemperate figures (excess and deficiency). The figure of “The Temperate Man” in the cartoon is a middle-class fellow (looking a bit like a “Murphy Man”) who is sitting in a chair at a table in some undesignated location (presumably not a saloon) drinking a beer and holding a pipe. Bemused, genial, perhaps a bit smug with self-satisfaction, this figure in the center is willing to let the other two fools be what they are, but is on the whole not affected by them. Forgive the pun, but they are merely side-shows for ordinary people who are getting on with the good life, which has a place for alcohol, but within limits. In sum: this is true temperance.

Compare this example from Puck’s with its rich juxtaposition of types of “Intemperance” to the earliest specimen of temperance humor that I have found in the history of our university. The 1916 Oracle includes a set of affectionate “roasts” about the ICU faculty, one of which was: “Professor Bailey drinks – water – when he is thirsty.” Viewed in isolation, this is such a feeble attempt at a joke, one almost feels embarrassed for our predecessors. When viewed in context as one of a dozen or so gentle roasts of the faculty, we can be more charitable. This was a genuinely affectionate jest about alumnus Warren Bailey, who during his student days in the ICU Academy had been the subject of many jokes, and obviously could take a joke. This is also one of very few examples of temperance humor that exists in surviving sources of student culture – the newspaper after 1922 and the yearbook continuously after 1916.* So we don’t have a rich trove of humor from the Temperance Movement and Prohibition-era in our institutional history.

However, I have identified seven “exhibits” that offer glimpses into the institutional culture during the period in which the temperance culture of the university changes. Or, rather, as I choose to put it in the title of this essay: this is the era of “temperance lost.”

I hasten to say that this literary echo – Milton’s Paradise Lost – is not intended to suggest that the story of temperance at Indiana Central is epic. Indeed, it was not. However, we know that the battle outside the neighborhood was a decades-long struggle between the “wets” and the “dry” forces, and at least a few people in the neighborhood were active participants.

Exhibit A: The 1916 Oracle Depiction of the History and Purpose of Indiana Central

As it happens, I have found a remarkable statement about “the purpose and history” of ICU in the same issue of the Oracle in which the gentle roast of Warren Bailey appears that I think can be read as an expression of the temperance culture. This text appears along with photographs of the leaders of the United Brethren Church, conference superintendents, and the (national) Secretary of the Board of Education for the UB Church. Photos of such personages are not typically found in yearbooks; they are not part of the student culture of the university. But Irby J. Good had just completed his first full year as president, and he is representing the church to the students and vice versa. If all we had to use was this one document to talk about the mission of ICU in 1916, the place sounds quite “Dry.” Consider the excerpt below:

“The purpose of the church is to provide training in the college courses under such influences as will elevate the ideals, heighten the ambition, keep pure the moral and spiritual life and strengthen the church for the larger duties to society. Thus the church and the state will have leaders trained and devoted to the best interests of society ready to apply themselves to the hardest problems.” (65).

Written about the same time that the state of Indiana decided to “go dry,” this text never uses the words temperance or prohibition, but it displays what I think is accurate to describe as a temperance sensibility, which is best displayed in the conviction that all parties – church, state, etc. – must tackle “the hardest problems” (saloons?) out of concern for “the best interests of society.”

While it is certainly possible that someone could use this same language and not be a Republican (like Irby J. Good), it would have been very unlikely that such a person would be have been a Wet in Indiana in 1916. More likely, I would argue, is the possibility that someone who is advocating to “make the map all white” is also trying to “keep pure the moral and spiritual life” of students who were the progeny of the United Brethren in Christ Church, which then owned and operated Indiana Central College.

That conclusion is reinforced, I think, by Good’s subsequent statement:

“Great care was taken in the founding of the leading student organizations. Two Literary Societies, Christian Associations, Music Clubs, Volunteer Bands, and the regular associations of the local church have become a distinct part of the student life, and their splendid work is a real index to the spirit and work of the college.” (65)

Good’s selection is interesting both for what he includes and what he sets aside. The phrase “real index of the spirit and work of the college” is the sort of quasi-social science language that was beginning to be used in American public policy circles to make claims based on social demography. Whether he realizes it or not, President Good has set up a hierarchy between two kinds of student experiences. There is the “real index” aspect of student culture that is for the church, and then there are the other activities — more secular endeavors — that are not significant for the church’s purpose according to Good.

I can imagine that some students might have taken exception to the omission of sports from Good’s quip about the “real index to the spirit and work of the college.” (But we shouldn’t sell Irby Good short. He was the pitcher on the first baseball team, and also played basketball while still in his 20s. He certainly enjoyed sports.) Notice that this particular explication is trying to spell out the “spirit” of the college in relation to what we now call “co-curricular” activities, the kinds of things that could be counted as part of the “work” students were doing to develop their personal culture. Good does not list the various “extracurricular” activities in the criteria to be used for the “real index” of the spirit of ICU.

That kind of selectivity might have irritated William Pitt Morgan, who occupied an unusual status not unlike the situation Irby Good during his own student years a decade before. Will was both a student (a junior in standing) and a faculty member (teaching art). In addition to being the star basketball player, Morgan’s academic interests spanned the humanities and the sciences. However, Will Morgan was not involved in any of the activities that Good regarded as part of “the splendid work” of the college. To make matters even more interesting (to me at least), Morgan was involved in the production of the yearbook as the advisor to the students who formed the staff of The Oracle for what is only the second volume of the yearbook (the first produced in 1909).

Imagine Will Morgan (the art instructor) reviewing the work of the yearbook staff; he may have raised his quizzical brow about what a “real index” is for judging the mission of the university, particularly given that much of what he is involved in doing is not covered by that way of mapping what was important. Here we have a glimpse of possible tensions that faculty and students may have felt at a moment when the state of Indiana had recently decided to prohibit the sale and distribution of alcohol and the Anti-Saloon League had embarked on its national campaign in alliance with the WCTU. There is not much room for humor in this situation, but in view of what happened over the next three decades, it is interesting to consider what Temperance looked like at ICU in those days. President Good is leading the Church’s College in the context of the “Dry” cause. Quite possibly, Will Morgan or others who did not advocate Prohibition looked on with skepticism given the newly declared purpose of the college.

EXHIBIT B: The September 1924 “The Spirit of I.C.C” editorial in The Reflector

Consider a second specimen from the Prohibition era. This is a curious article, especially given that it is about campus traditions. But it was also written in the awareness of change, brought about by growth in the student body, which now numbered 350 students. The editorial staff, a dozen or so upper-class students, was only the third team in the history of the ICC student newspaper – which had been founded back in 1922. Carroll W. Butler & Roy V. Davis were trying to cultivate a sense of community as witness the various short articles inviting new and returning students to participate in various campus activities ranging from volunteering to work with the 1925 Oracle yearbook staff to Christian life activities of the YMCA & YWCA, etc.

The title of the piece reflects the central query that the editors are inviting fellow students to consider. In the first paragraph, they call attention to the “glorious heritage” and “splendid traditions” that they all have received from the sponsoring church which invites them to Christlike service. Although they don’t actually name the United Brethren in Christ Church, their choice of pious language – “patriarchs” — for the founders’ placemaking efforts is respectful. (They know that their journalistic efforts are going to be read by some trustees and alumni some of which they probably know.)

The central paragraph focuses on three interrelated aspects of the present moment. Until now, “these traditions have always been upheld at I.C.C.” As the college grows year by year, the student body becomes “more cosmopolitan,” thereby creating tensions with respect to these college traditions of the church’s origin. Therefore, everyone needs to cooperate – newcomers and folks already at home in the UB Church – in order for the college to succeed with its mission as a college of the church.

In the final paragraph, the writers actually name some of these traditions, beginning with the one that seems to be under negotiation at the time, namely smoking cigarettes. “The use of tobacco in any form has always been frowned upon anywhere and absolutely tabooed on the campus.” We know from subsequent history during and after WWII that ICC leaders would continue to struggle with how to administer this expectation for decades. (I wonder which regime has been more successful over the past ten decades.)

I was even more intrigued to discover what the other three or four issues were: The first set of expectations is the “gentlemanly behavior” that upper-class students are expected to show new students. Put most positively, ICC students pride themselves in showing “Christian hospitality.” More specifically, “no rough or savage hazing methods” are permitted. The second pairing focused on sabbath observance (no athletic events), and the expectation that everyone will attend church worship (“at least one service”).

These are fascinating ways that ICC ordered space and time. Notice that ICC students are voicing these expectations. Although it might be possible to reconstruct such mores and “taboos” from reading presidential correspondence and the minutes of Board of Trustees meetings, we don’t have the kind of documentation to be able to spell out the scaffolding of student development in relation to the student experience.

The editors conclude this piece by encouraging fellow students to “boost together” during the 1924-25 year “to uphold the splendid ideals of old I.C.C.” I suspect that most readers will have noticed that there was an issue that was not discussed in this piece, namely the college’s rule against the use of beverage alcohol. We can infer that either this was not one of the traditions being challenged at that juncture (by more cosmopolitan students) or that if there was tension about this feature of the institutional culture of I.C.C. there was no purpose in bringing it up since the Prohibition regime in place nationally as well as in the state of Indiana made this a moot point.

I believe this brief (unsigned) article about “the Spirit of I.C.C.” is probably the best specimen we have (at present at least) of the student experience from the time before the loss of the temperance tradition. Only eight years later, the situation looks different.

EXHIBIT C: Shortly Before the 1932 National Election

The third specimen in my small collection displays an emergent awareness that everyone is not on the same page when it comes to political affiliation and quite possibly judgments about the wisdom of Prohibition. Elections do not always bring about dramatic changes, but judging from the perspectives of student journalist s in the fall of 1932, that was the case in the year that (Republican) Herbert Hoover was defeated by (Democrat) Franklin Delano Roosevelt. We are fortunate to have some data to indicate the magnitude of the change. In October 1932, the faculty and students at ICC decided to carry out a straw vote.

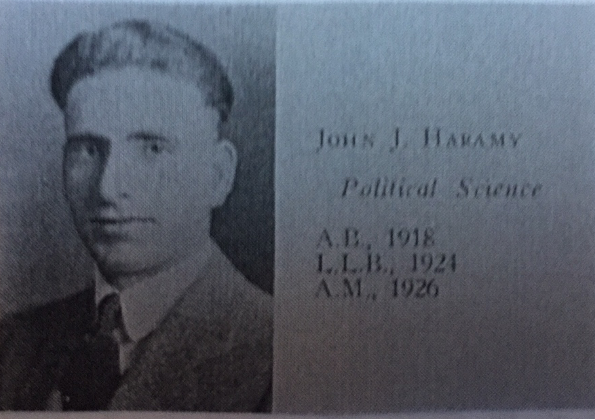

This venture was organized and carried out by the staff of The Reflector newspaper in collaboration with Prof. J. J. Haramy, who was the rather charismatic professor of political science and history who was born in Jerusalem, trained in law, and sometimes served as a Quaker pastor. One of the regular Chapel hours was devoted to preparing the students to participate in the mock election. Prof. Haramy “gave a short talk on the platforms of the four parties and . . . the main issues involved in each.” The result of this vote was reported in the October 28, 1932 issue of The Reflector (Vol. 11, No. 4).

The total college vote was listed for four parties: Republicans (Herbert Hoover), Democrats (Franklin D. Roosevelt), Socialist (Norman Thomas), and Prohibition (Upshaw). The breakdown in statistics included the votes of faculty (male & female) as well as separate totals for “college men” and “college women.” The headline displayed surprise: “PRESIDENT HOOVER RECEIVES 218 VOTES TO DEFEAT ROOSEVELT” The vote totals provoked much conversation in the seven days before the election.

Report of the Mock Election: 20 of 23 faculty voted for Hoover, one male faculty voted for Roosevelt, one female faculty cast her ballot for Thomas and the other faculty woman voted for Upshaw. The student body, which was twelve times the size of the faculty grouping, cast 192 votes for the Republican candidate, 94 votes for the Democrat, 13 votes for the Socialist, and four voted for the Prohibition candidate.

The total college vote reported by The Reflector staff:

- Hoover — 218

- Roosevelt — 93

- Thomas — 24

- Upshaw – 5

Because this was a straw vote it is not out of the question that the faculty agreed among themselves to ensure that there was at least one vote for each of the candidates so that no students would feel isolated as a result of this learning exercise. This was, after all, a co-curricular experience; the goal of which was to learn about the duties of citizenship. Haramy’s presentation in chapel – like guest speakers from WCTU and ASL – was intended to shape students in productive ways for participation as citizens as well as in their Christian self-understanding.

On the other hand, it is also quite possible that these judgments were not as privatized as we assume that they should be in the 21st century. In a few instances, the faculty would have been born prior to the legal enactment of the secret ballot in the 1890s. There were also non-civic traditions that might have played a role in the way the vote was enacted. The United Brethren Church’s tradition of face-to-face public engagement, which included the annual elections of conference superintendents (which might still have taken place with hands-raised or voice votes), was a cherished tradition.

If The Reflector’s editorial commentary is to be believed, this exercise did in fact reveal something to the students that they had not known before. The reporter offered the following summary comments: “The returns of the election bears proof of the fact that the student body in the main is a strong supporter of the Republican party. This fact has long been a matter of doubt, although it was known that the faculty presented a strong Republican front, which was further brought out in the election returns.”

The results may have produced conversations due to the likelihood that some members of the ICC community may have thought that they could identify who voted for the Democratic candidate. My guess is that the most likely male faculty members to vote Democrat would have been Prof. Cummins (Philosophy) or Prof. Haramy (History and Political Science) and the most likely female faculty to vote for Roosevelt would have been Anna Dale Kek (Latin/Registrar). No doubt, the more pious Teetotalers on campus would have raised their eyebrows in wonderment at how Prof. Morgan had voted in the election. They might have speculated about his disposition, but likely no one ever knew. Morgan was all about science – and sports! Church and politics, not so much.

(It is also possible that the outlier votes for the Socialist and Prohibitionist candidates might have been attempts to convey that there was room for all parties at ICC, although it is hard to imagine that President Good would have countenanced the manipulation of the secret ballot.)

Exhibit D: The Aftermath of the 1932 Election at Indiana Central College

The actual election for President of the United States took place on the first Tuesday of November 1932. And the result was the opposite of the total college vote at Indiana Central College that had taken place two weeks earlier. The fact that Herbert Hoover lost in a landslide advertised the fact that the majority of the campus now found itself in the minority (nationally speaking). This shift also portended a reversal in outcomes for the Prohibition of alcohol across the land, a prospect that also quickly began to register on the ICC community with the legalization of “3.2 beer” as early as April 1933.

The Nov. 11, 1932 issue of The Reflector includes a brief student editorial commentary entitled “After Election Politics.”

“Now that the election is over, we face a period of four years in which our nation will either be engaged in a constructive or destructive program. It is true that the results were not according to the general approval of our student body, yet it behooves us to look on these next four years with almost exaggerated optimism.”

“No party can pass a bill without the majority of the people approving it, that is the glory of our democracy. Thus, as issues approach, for instance, the Prohibition measure; we must make our wants known. As those of the American people, then no measure can be inaugurated against our will.”

“Many of our student body voted last Tuesday and they have already realized participation in running the government. Within the next four years many more of us will be voting and as a unity of college graduates should face these next four years with an open mind, but with determined conviction to support the highest ideas of American manhood and womanhood.”

Although this post-election editorial is unsigned, the masthead lists Julia Ann Sprague as the Editor-in-Chief that year, so we can assume she was involved. Ms. Sprague et al. display some of the confusion that students and even some faculty at ICC experienced in the wake of the election of 1932.

Cliched statements such as, “no measure can be inaugurated against our will” sit uneasily with pieties about “the highest ideas” about gendered role expectations. On the other hand, we cannot discount the possibility that this language of “American manhood and womanhood” still retained some moral force associated with temperance for Julia Ann Sprague and her classmates.

Suddenly, the idea that Prohibition might be defeated, in the wake of the presidential election, was a much more realistic prospect than anyone would have thought before.

We are left to speculate. Perhaps it was the emerging recognition that the Constitutional amendment had failed at the level of lived reality. If that is the case, then perhaps students like Julia Ann Sprague realized that hypocrisy was more prevalent than abstinence when it came to the consumption of alcohol. But then, it was no longer clear that Temperance had a home in University Heights. Or if she did, it was no longer a map that was “all white.”

EXHIBIT E: The Perceived Loss of Faculty Support for the “Dry” Stance at ICC

In 1942, President Good received a “letter of protest” from a former student at Indiana Central. Indeed, Darius H. Pellet and his wife Celia Austin Pellet would have been one of the first “clergy couples” who were enrolled (1914-1916) before World War I. Both served as student pastors for a time. Perhaps in part because of the war, neither actually graduated but their names show up on some of the earliest exceptions made by the faculty for excused absences. Darius had been an active student, having served as the secretary/treasurer of the YMCA. At the time that Pellet wrote the letter (a quarter of a century after he was a student), he was serving as the pastor of the congregation of United Brethren in Brook, Indiana – a community with a strong United Brethren presence centrally located in the Midwest. So the person bringing the complaint was not just any pastor. Although not actually an alumnus, he was part of the church constituency. If Pellet had questions about whether ICC students were deviating from social mores then-President Good had a problem.

The faculty member in question was also well-placed. Prof. William P. Morgan was an alumnus (Class of 1916). He was a multi-talented man –a star athlete, an artist, as well as an icon of intellectual rigor, who had distinguished himself as a basketball player and budding young scientist during his student years before suffering an injury that resulted in the amputation of one leg. (Pellet and Morgan also overlapped during their student years.)

This was not the first time that church leaders had raised questions about whether Prof. Morgan was sufficiently “orthodox” in his beliefs. Some had questioned whether he even had religious convictions. He was widely perceived to be the most rigorous professor on the faculty, renowned for his scientific focus and academic integrity. Previously, President Good had defended Morgan to critics.

In sum: this was a site for clashing sensibilities about matters moral and scientific.

In his centennial history, Prof. Frederick D. Hill provides a detailed summary of the situation: Rev. Pellet claimed he had heard complaints “from students and their parents, both ministerial and lay” for several years. On this occasion, Pellet wrote Good to report about “a letter from a student in Dr. Morgan’s ‘Hygiene’ class, and he could keep quiet no longer about the inconsistencies between what the college was teaching and the public image, especially its stance against alcoholic beverages” (Hill, 288).

Rev. Pellet denounced the substance of what students learned in the Hygiene class by Dr. Morgan, Hill reported, “as incompatible with Christian teaching and contradictory to both the Old and New Testaments.” (Rev. Pellet does not bother to remind Good about the United Brethren Church’s stance on Temperance. See MM #67). By emphasizing what he judges to be the lack of regard for biblical authority, Pellet is choosing to indict Indiana Central in a way that would embarrass President Good with the church constituency at a time when the financial situation at the college was already difficult due to enrollment decline with the start of World War II.

Pellet concluded: “There is little wonder that you have had trouble with your students drinking and smoking, and with girls sneaking down the fire escape and midnight go be with their boyfriends.” This latter claim, of course, is intended to convey that the college is no longer carrying out its responsibilities to act in loco parentis.

Pellet listed several additional concerns (without offering any documentation) based on the student’s reported experience in Dr. Morgan’s course:

- Alcohol is not habit-forming.

- Alcohol does not cause ulcers of the stomach and bad liver

- The consumption of alcohol by a pregnant woman would not affect her baby unless she drank to excess.

- One is drunk or not according to the alcoholic content of his blood, not the quantity of liquor he has consumed.

One wonders about the first of these concerns. Even in the 1940s, there was extensive literature about addiction. Perhaps the student was providing a selective report to indict the instructor. Perhaps Prof. Morgan simply offered an aside about the psychology of habits and futures, to reinforce the ethic of personal responsibility for creating and sustaining habits of good hygiene and personal health.

Pellet also reports one particularly objectionable aspect of Prof. Morgan’s teaching: The instructor had led students to believe that anti-alcohol information disseminated by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union was “bunk.” Here also, it would be interesting to know whether the information that had been distributed by WCTU was in written form or was only a product of oral tradition. By this point, it could have been either.

Much depends on how active the Marion County Chapter of the WCTU was during World War II, and whether the pattern of the group speaking to students during chapel services that occurred in the 1920s had continued after the repeal of Prohibition. Given that the local chapter of the WCTU was located at University Heights United Brethren Church (located after 1931 across the street from the University), this is another point at which roles matter. Prof. Morgan, who was also a member at UHUBC – or at least had been earlier in his career at a point in the 1920s when complaints about his perceived lack of religious orthodoxy had surfaced — may or may not have been responding to local circumstances. Without specific documentation, it is difficult to know how deep the disagreement between scientific and religious claims was at this juncture.

One wonders if this latter claim was received as more of a perceived insult to fading sources of moral authority in a rapidly changing wartime culture than as an actual challenge to the sources for instruction. By this point, the alliance between the United Brethren Church leadership, the WCTU, and the Anti-Saloon League, which had been so potent in the first two decades of the 20th century, had fallen apart in the wake of the defeat of Prohibition. But most colleges, Indiana Central included, continued to forbid alcohol consumption on campus for a variety of reasons including legal age restrictions.

The accusations against Dr. Morgan are also telling because the 1933 revocation of the Volstead Act, which had changed the rules for buying, selling, possession, and consumption of alcohol, had already removed the legal restrictions that reinforced a temperance stance. Except for “blue law” restrictions on the times and days of the week when alcohol could be bought and sold, whatever semi-public mores associated with the consumption of alcohol that may have remained in University Heights were no longer reinforced by national, state, and local legal codes.

Pellet also objected to the textbook Dr. Morgan had chosen to use in the course on Hygiene. The student informant was scandalized to learn that “two bottles of beer contained the same amount of nourishment as one bottle of milk.” This latter citation appears to have been taken out of context and may have been used because it violated the kind of commonsense reasoning that advocates of Prohibition had long relied upon to support its contentions that alcohol consumption was unwholesome.

Pellet’s letter is a fascinating specimen because it illustrates the attempt of more conservative members of the United Brethren church constituency to police the campus ethos. It pits scientific sources versus the moral reform efforts of the church and Prohibitionist crusaders. I doubt that Prof. Morgan had the same “facts” in view at this juncture as Prof. Stoneburner had in mind when he addressed the students in 1931 (see MM #68), but there may have been some overlap that it is not possible to see eight decades later. Regardless, the appeal to science is another marker in the breakdown of the perception of a shared ethos of temperance in University Heights. Where there are no longer shared sources of moral authority, it is difficult for the college to cultivate shared practices such as abstinence from beverage alcohol.

(I am tempted to read into this incident more than Frederick Hill discusses. As I have already noted, Morgan was both a student and a faculty member in 1915-16 teaching art while working on his bachelor’s degree and playing varsity basketball. That same year, Pellet was a student pastor who participated in the YMCA fellowship activities. No doubt the two knew each other, but they still may not have known each other well. And they may or may not have perceived their individual student experiences according to the measures of the “real index” that President Good touted in the 1916 Oracle. Regardless, by 1942, Pellet’s criticisms, which charge Good with failing to uphold “dry doctrine,” start to look intemperate, even if he may have thought that he was simply applying the standards of expectation that had been in place when he was a student. Either way, Prof. Morgan starts to look like the “Temperate Man” in Gillam’s 1882 cartoon except that it would have been possible for him to think that abstinence was the best way forward – as a prudential matter – and still disagree with Good’s version of Teetotalism.)

EXHIBIT F: Pres. Good Requests that Faculty Sign a Statement of Support

In his centennial history, Frederick Hill also goes out of his way to juxtapose the 1942 incident when Pellet charged Morgan with teaching anti-temperance views with an earlier effort by President Good to reinforce the faculty support for the social mores of the campus. In 1939, Good put together a page-long list of the moral stances that ICU holds and asks (demands?) members of the board of trustees and the faculty to sign a statement indicating that they support these concerns. Alcohol is only one of the items on the list. Tobacco appears to be one focus of concern. The President is clearly angry that others are not upholding the standards on tobacco, and student deportment in the ways that he thinks they should.

Although Good issued the imperative that everyone should sign the document, we also know that Frederick Hill reports that he could not find this document in the archive of documents from Good’s tenure as president. (All we have is the handwritten draft of the queries.) Perhaps Good met with enough refusals that it became counter-productive to make public the list of supporters? Was this the only battle of wills? We simply do not know. But we know enough about the last five years of Good’s tenure to be able to say that faculty found him to be authoritarian.

If the board had not taken action when it did in June 1944, then ICC would have lost some of its most talented faculty and administrators. Dr. Frederick D. Hill provides a detailed discussion (232-233). Faculty who had long been frustrated began to be demoralized; they were tempted to leave after “trying to work with President Good when he expected them to work for him.” Prof. Morgan ’19 almost left in 1943 to take a position as a scientist in industry. The following year he told colleagues that he would leave if Good’s contract was renewed. Meanwhile, the Board of Trustees created the Greater Indiana Central College Committee, which in effect was charged with finding a way forward in anticipation of the end of World War II.

I think it is tricky for those of us who are standing in the third decade of the 21st century to know how to register the conflicts that existed between President Good and Prof. Morgan in the 1940s without misjudging the situation. One danger is to overstate the differences — as if their disagreement about alcohol was a mini-version of the culture wars. That may not have been the case. They both liked to appeal to the facts of a matter, and they both expressed themselves in a plainspoken way. They could have agreed on some matters and disagreed on others. At the same time, Morgan was a scientist and scholar. For him, precise judgments must be anchored in evidence. Good was the embodiment of “downright devotion to the cause” – the signature phrase that Frederick Hill used as the title of his centennial history. Irby J. Good operated out of the sense that if something “ought to be done,” then that is what he and everyone else will do. Although Good was deeply committed to Temperance, he was anything but temperate.

After the war, the greater diversity of faculty and students would have meant that President Good would have had great difficulty managing the loss of support for his version of temperance. But everyone was spared that prospect.

EXHIBIT G: Irby J. Good’s Retirement in June 1944 and Death in January 1945.

In MM #67 & #68, I discussed how Mother Roberts served as an icon of the Temperance Movement. Her death in 1950 may be one of the last markers of the WCTU temperance witness associated with the EUB Church in Indiana. But by that time, Alva Button Roberts had not been associated with ICC for four decades. My sense is that if there is a symbolic marker of the loss of the Temperance ethos at ICC, it is five years earlier.

President Good’s death on Feb. 25, 1945— shortly after speaking at a temperance meeting in Wabash, Indiana on behalf of United Dry Forces of Indiana — is an apt way to mark the decline of the temperance ethos — as a set of moral teachings and institutional expectations for faculty, staff, and students. He died as he had lived, and then he became part of “the great cloud of witnesses.”

He represents the last of the old; his successor I. Lynd Esch was the first of the new. The student editors of the 1945 edition of The Oracle yearbook, who greeted the incoming president while showing due respect to his predecessor, provided the best obituary for Good I have yet seen. This excerpt displays the theme that summarized his 29-year tenure as president and four-decade association with ICC, going back to the earliest conversation about its founding.

“He was a Crusader, leading the infant college through the hard days of childhood diseases and adolescent awkwardnesses when folk found it easy to say, ‘It will never survive!… After thirty-five years of service to the college…he…continued to crusade…and died while serving as legislative counsel for United Dry Forces of Indiana. He still crusades. . . in the broad horizons of eternity. . .” (1945 Oracle: 65).

“He was a Crusader, leading the infant college through the hard days of childhood diseases and adolescent awkwardnesses when folk found it easy to say, ‘It will never survive!… After thirty-five years of service to the college…he…continued to crusade…and died while serving as legislative counsel for United Dry Forces of Indiana. He still crusades. . . in the broad horizons of eternity. . .” (1945 Oracle: 65).

The description fits the life Good lived, and as I shall discuss in MM #71, that is part of the reason Good is such a fascinating figure. We do not resonate with the object of his great Cause, and yet one cannot but admire his determination and perseverance.

No one appears to have stepped forward at Indiana Central to fill the void in the temperance ethos created by Irby J. Good’s death. Or, to view it from a different framework, like most other institutions in American society, Indiana Central College experienced the new realities that resulted from the restructuring of American life during World War II. The influence of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union declined. After 1945, we don’t find published accounts of temperance leaders speaking on campus. Occasionally, the WCTU. schedules a luncheon meeting on campus (1962) and I found a brief correspondence between President Esch and a leader of the WCTU – but not from Indiana. Students at ICC no longer encountered the WCTU as a set of living witnesses. Not surprisingly, the influence fades rather quickly in the post-war period once the dry doctrine is no longer communicated as an official stance of the institution and informally as the expectation for students.

Once President Good died, it was no longer viable to talk about a crusade for temperance at ICC. That does not mean that there are no advocates for temperance at ICC after 1945, but I think it does mean that those who were still alive did not give voice to their convictions in a way that students at ICC would have found compelling. For example, Mrs. Good continued to live at 4102 Otterbein Avenue until shortly before her death in 1974. I think it is likely that she and others of her generation associated with the college continued to live by abstinence, but Mabel Good was never a Crusader in the way her husband had always been. At her death, she was not memorialized as “Mother Good” (as she might have been if she had been a life member of the WCTU).

When you know where Temperance Crusaders once lived in the neighborhood, but no longer have a Crusade, what is left is nothing less than “temperance lost.”

*******************

Coming in early 2021, MM#70 will focus on changes in the way that alcohol rules were interpreted at ICC as part of student conduct codes after World War II.

As always, please feel free to share your own thoughts and responses with me at missionmatters@uindy.edu. In the meantime, don’t forget that UIndy’s mission matters!