Prof’s writing probes politics of language

You’ve probably never heard of the pidgin language Camfranglais, but it is gradually changing cultural and political life in the west central African Republic of Cameroon, ruled for more than three decades by the same authoritarian president.

A combination of French, English and indigenous languages, Camfranglais plays a central role in two books published this past year by Assistant Professor Peter Wuteh Vakunta, a native of Cameroon who teaches French in UIndy’s Department of Modern Languages.

One work, published in December by the Cameroon-based Langaa Research and Publishing, is an anthology of Vakunta’s poems in the language titled Speak Camfranglais pour un Renouveau Onglais, which translates to Speak Camfranglais for a Cameroonian Renewal.

“It’s a hybrid language started by high school students who wanted to speak about things that are not entirely polite, so the school officials and their parents would not understand,” Vakunta explains. “This is no longer just a language of the streets. It has now become a language of literature.”

It is also a language of resistance, despite its roots in the post-World War I colonization of the area by the British and French. Since surfacing in the 1970s, Camfranglais has become a channel by which artists and activists can evade government censorship and speak to the common people.

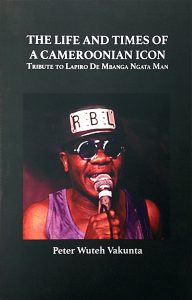

Vakunta explores the legacy of one such artist in his latest book, The Life and Times of a Cameroonian Icon: Tribute to Lapiro de Mbanga Ngata Man, published in April by Langaa.

Lapiro de Mbanga, who died in March, was a guitarist and singer in the local makossa musical style who used his popularity to criticize government policy and corruption. He was imprisoned for three years after his song “Constitution constipée” (“Constipated Constitution”) became the anthem for anti-government protests in 2008. Vakunta returned to Cameroon in 2012 for an extensive interview with Lapiro (in French) that can be seen on YouTube.

Lapiro de Mbanga, who died in March, was a guitarist and singer in the local makossa musical style who used his popularity to criticize government policy and corruption. He was imprisoned for three years after his song “Constitution constipée” (“Constipated Constitution”) became the anthem for anti-government protests in 2008. Vakunta returned to Cameroon in 2012 for an extensive interview with Lapiro (in French) that can be seen on YouTube.

“He was very anti-establishment, hated corruption, hated the rape of democracy,” Vakunta says.

When Lapiro died in March, after being exiled to the United States, Vakunta’s publisher asked him to compile his notes and previous writings into a book, which also includes transcriptions of many of the artist’s songs.

“I had a ton of stuff,” says Vakunta, whose prolific literary output also includes short stories and novels. His two latest works, and many others, are available through Amazon.