Mission Matters #66 – The Virtue of Temperance Revisited

By Michael G. Cartwright, Vice President for University Mission and Associate Professor of Philosophy & Religion

One hundred years ago, Prohibition began. In the parlance of the time, that meant that the “teetotalist” version of temperance was mandated for the entire country. That meant that all US citizens, not just the folks in University Heights, which had been created as a “temperance community” fifteen years before, had to conform to the same set of moral rules.

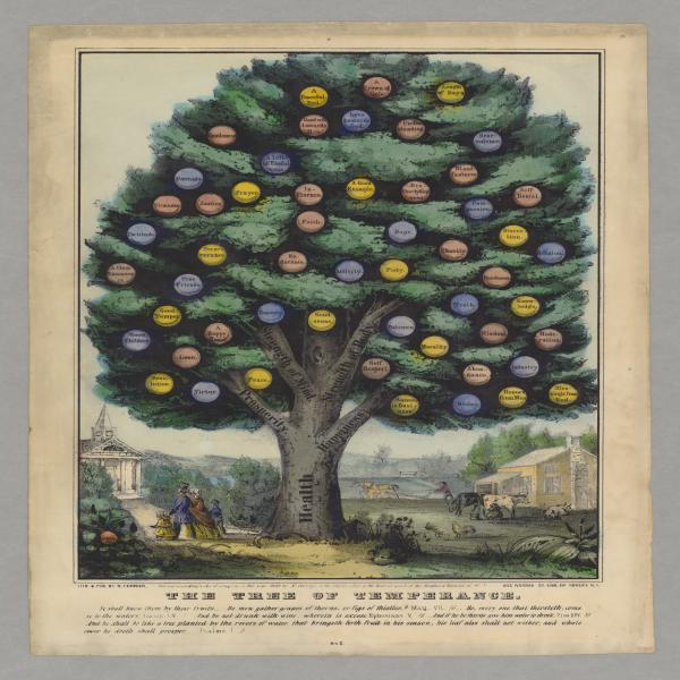

Unfortunately, the virtue of temperance has been invoked for rather intemperate purposes, most famously by advocates of Prohibition. But how could that be? According to Xenophon, temperance is “moderation in all things healthful; total abstinence from all things harmful.”

Unfortunately, the virtue of temperance has been invoked for rather intemperate purposes, most famously by advocates of Prohibition. But how could that be? According to Xenophon, temperance is “moderation in all things healthful; total abstinence from all things harmful.”

Ancient Greek philosophers aren’t much quoted these days in popular culture (unless you happen to pick up a witty book like The Socrates Express). A hundred years ago, people lived in a different world, conceptually speaking. Xenophon’s definition actually was much quoted by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (W.C.T.U.), a group of crusaders who identified the consumption of beverage alcohol as inherently evil.

Due to the latter group’s involvement with the founding generation of Indiana Central University, we know that students were conversant with this conception of Temperance as a moral virtue. That fact alone provides sufficient reason why I decided to re-engage the conversation. I have identified three additional reasons.

First, there is renewed interest in temperance – understood as “a placemaking virtue” – by advocates of local economy such as the Kentucky agrarian writer Wendell Berry and writers associated with the Front Porch Republic magazine, among others. Faculty and staff associated with UIndy have been known to advocate urban “localist” approaches to community building that are consonant with this interest even if they do not invoke the category of Temperance.

A second reason is more complicated: we know that Temperance was intertwined with the United Brethren Church’s efforts to found a college in the neighborhood. Prohibition failed. The University survives. The United Brethren Church merged with the Evangelical Church, and later with the Methodists to form the United Methodist Church (UMC), and now in 2020, that denomination is on the verge of splitting due to a different culture war. More than a few people on the UIndy campus associate the university’s rules about beverage alcohol consumption with the church affiliation. Sadly that is sometimes all they know about the rather complicated relationship the university has had with the church that founded it 118 years ago. This suggests (to me) that the culture of our campus has been shaped to some extent by prohibitionist understandings of alcohol, but only rarely has there been public discussion of the matter. Talking about our history with alcohol is long overdue.

Finally, given the university’s identity as an intentionally pluralist comprehensive church-related university that seeks to be anti-racist and hospitable, we can inquire about the future prospects for this particular mark of moral excellence in the 21st century.

I. Temperance as a Virtue of Place?

“What ecological insight has done is reveal again the practical foundations of ancient morality. . . . [T]emperance is not just a spiritual discipline, but a practical necessity, no less than food or water or air. . . . Finally, it shows us the possibility of a healthful economy that is at once physical and spiritual.”

–Wendell Berry, Commencement Address given at Centre College, 1978

We won’t get very far with a discussion of Temperance at Indiana Central before we run into the notion of “placemaking,” an umbrella term under which quite different approaches to community building, landscape architecture, and urban planning have clustered over the past half-century. Not all placemaking endeavors pay attention to the past, but such ventures often do disrupt patterns of community that already exist whether their agents recognize what they are doing or not.

As our faculty colleague Kevin McKelvey said last year [in his response to Showers Lecturer Jennifer Craft’s presentation on Placemaking and the Arts], “Placemaking can be a troubling term because it implies that a place ‘needs to be made.’ But most places are already made. They already have people and a culture.” The question is what those who are in a position to do something choose to do with what is already in place. If you choose to keep it, then you can take responsibility. But we don’t always elect to do that; at times we opt to replace, or we displace and may not even bother to acknowledge what we have done.

Borrowing words from Craig Bartholomew, Prof. McKelvey clarifies: “placekeeping aims for implacement and reimplacement without displacement.” As he goes on to explain, “The practice of placekeeping acknowledges that a culture and its people already exist in a place. In this approach, artists, placemakers, and community leaders and organizations work to empower local residents so they can stay in their neighborhood and create the institutions or programs they need and remove barriers.”

I am grateful for Kevin’s careful reminder about the different kinds of agency involved in placemaking. I broadly concur with his convictions in these matters. I also believe these observations apply to colleges and universities, which often exist both as agents and sites of “placekeeping.” On the other hand, we know there are also circumstances in which we actively disrupt an ethos, either because it has proven to be dysfunctional or perhaps it has proven itself to be contrary to the common good or both.

There is no shortage of cases (de jure residential segregation by race, etc.). I don’t know anyone currently associated with UIndy who proposes to “reimplace” Prohibition in the neighborhood of the university. I think we are content to let it remain as a displaced ethos. Even so, I think we all could benefit from learning how that situation came about in University Heights, especially since Temperance may be the virtue that marks the greatest discontinuity between UIndy and the community of learning associated with the founders of the Indiana Central University. And yet, there remain ancient senses of “Temperance” as a standard of wholeness for how to think about healthy local economies (see the quotation by Wendell Berry above) that are not confined to the definitions associated with Prohibition.

II. Temperance as a Personal Virtue for Character Formation

The continuities and discontinuities about Temperance and the university are not confined to placemaking and placekeeping. They also have to do with how we think about personal standards of moral excellence. For instance, one of the oldest features of the university’s mission and purpose is character formation. That is an aspiration for both curricular and co-curricular programming oriented by the mission of the university that has been reaffirmed on many occasions, including the 2006-2007 vision statement that was disseminated during the administration of Beverley Pitts. The final words of that text affirm that the university has “a Christian tradition that emphasizes character formation and embraces diversity.”

Over the past quarter-century, the university has consistently displayed an “intentionally pluralist” paradigm of its church affiliation. During much of that time, I have led those conversations as the university continues to engage an ecumenical and interfaith approach to campus ministry. What has been less universally explicated is the aspect of character formation, which has been emphasized most consistently in the curricula of the Lantz Center for Christian Vocations and Formation and courses offered for undergraduates in various disciplines of the Shaheen College of Arts & Sciences. But you don’t have to look very far before you find language that approximates this concern in the curricula of the School of Nursing, the School of Business, and other professional schools, often closely linked with professional codes of ethics.

Even so, the ways faculty and staff pursue character formation today is quite different than the approaches taken by the founding generation of Indiana Central University. For J.T. Roberts and Irby J. Good, Alva Button Roberts, and Sybil Weaver, the virtue of temperance provided a primary paradigm for how to think about what it meant for students to become mature adults. And as I will explain, the explicitly Christian framework that the founders used was cast in ways that were gendered. We no longer aspire to instill notions of “manliness” and “womanliness” in the ways that the founders did, and you can probably name reasons that are pertinent to your own professional training or field of study, or perhaps the ways you and your colleagues think about gender and human sexuality today.

Simply put: the cultural conflicts of the Prohibition era disrupted the ways we came to think about character formation, and that is no less true of our university than it is of other communities of learning, but given some of the particularities of our origins, the conflictedness may be more persistent given that there has been so little discussion about the changes that occurred and why we remember so little of our own institutional history in these matters.

If you aren’t familiar with the tangled history of the temperance movement in American culture, this might be a good time to take a quick look at the Wikipedia article on the topic. Or better yet, you might take an afternoon to read the brilliant dissertation by Holly Berkley “From Self-Made Men to Crusading Women: The Gendered Evolution of the American Temperance Movement in the 19th Century” (Norman, OK: Univ. of Oklahoma, 2004). There are also plenty of resources about the temperance movement in Indiana and especially Marion County, such as Russell Pulliam’s fine article on “Temperance and Prohibition” in The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis (2004).

III. More about Temperance Still to Come

What is not readily available is an account of what transpired at Indiana Central University between 1905 and 1985 with respect to the Temperance Movement and Prohibition. There are still a few people on campus who remember the years between 1975 and 1985, but by that point the founding emphasis on temperance had disappeared. (The legacy of Prohibition has complicated matters considerably.) What we need to do is reconstruct the archive of memories associated with the temperance ethos that once existed on this campus. That is what I will try to provide in MM #67, “Founding a Temperance Community,” MM#68, “When Temperance Lived in University Heights,” and MM #69, “Temperance Lost at Indiana Central.”

I want to say at the outset that I am fully aware of the fact that there is much that I/we do not yet know about this aspect of our institutional heritage. My modest hope is that my own provisional explorations will stimulate UIndy faculty and students to do the kind of archival research that will uncover the rest of the story. Along the way, I will remind you of a few things about the intellectual history associated with the notion of the “cardinal virtues” – prudence, justice, temperance, and fortitude – that some of you may have forgotten or perhaps simply have not had the opportunity to think about before.

Early next semester, I will follow up with a final reflection (MM #70) about contemporary thoughts on Temperance, which strike me as much more fruitful than “teetotalism” about alcoholic beverages.

As always, please feel free to share your own thoughts and responses with me at missionmatters@uindy.edu. In the meantime, don’t forget that UIndy’s mission matters!