Mission Matters #68 – When Temperance Lived in University Heights, 1905-1935

By Michael G. Cartwright, Vice President for University Mission and Associate Professor of Philosophy & Religion

This year we are exploring marks of excellence that can be discerned in the past and present of our institution. Virtues are displayed in the context of practices and social relationships, they reflect moral traditions, they are embodied by exemplars, and they are sustained by institutions such as universities. This month, we are exploring the virtue of temperance, which was closely tied to the founding generation of Indiana Central University. In MM#67, I described what we know about the Founders’ efforts to create a Temperance community in University Heights. This essay focuses on what we know about student engagement with Temperance before and during Prohibition.

Temperance was determined to make the place her own. After all, everyone agreed that University Heights would be governed by the “local option,” which prohibited the sale and distribution of alcohol from Hanna to Lawrence and Weaver to State Avenues. Parents of the students who enrolled at Indiana Central University were assured that their children would be living in a campus community where, as an ICU brochures put it, “The environment is wholesome,” “The faculty is made up of Christian men and Christian women,” “The social life is Clean and Elevating” and “It is a Safe Place for your Son and Daughter.”

Temperance was determined to make the place her own. After all, everyone agreed that University Heights would be governed by the “local option,” which prohibited the sale and distribution of alcohol from Hanna to Lawrence and Weaver to State Avenues. Parents of the students who enrolled at Indiana Central University were assured that their children would be living in a campus community where, as an ICU brochures put it, “The environment is wholesome,” “The faculty is made up of Christian men and Christian women,” “The social life is Clean and Elevating” and “It is a Safe Place for your Son and Daughter.”

When students arrived on campus during the first three years (1905-1908), they were greeted by President J.T. Roberts and Rev. Alva Button Roberts. “Mother Roberts” as she was known at various points in her life was a longtime member of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and was famous for being “the first lady circuit rider” in the United Brethren Church (serving a five-church circuit near Greenup, Illinois, in the early 1890s). We don’t know as much about Alva Button Roberts as we would like to know, but she appears to have been one of those determined women who opted for the WCTU’s understanding of women’s leadership when the former parted ways with the early feminist movement.

So Mother Roberts made the meals for students, and no doubt she counseled the disappointed and where necessary chastened those who failed to live up to the expectations that she and United Brethren faculty had for students in the early days.

From her teenage years onward, Alva attracted attention because she embodied roles that were strongly associated with the masculine gender. As a teenager, she learned how to set type and worked in a print shop in Greenup, Illinois. She was bothered by the Methodist Church’s refusal to ordain women in the 1880s, so she joined the United Brethren in Christ, and was appointed in 1889 by Bishop Kephart to serve five churches in the Lower Wabash Conference of the United Brethren Church. When we place her 50-year membership in the WCTU alongside those facts of the matter, I think there is sufficient reason to wonder about the way this founding leader displayed non-traditional gender roles while also serving as a mother figure at various points in her life. (Obviously, this is another subject for further study for some enterprising UIndy students to pursue.)

Living Under the House Rules of Temperance

What about the rules that students who enrolled at ICU were expected to obey? Did they have to be teetotalers? Here, we really do confront L. H. Hartley’s wry observation: “The past is a foreign country; they do things different there.”

Temperance norms for students are not specified as explicit rules, and therefore they are not readily visible as such to 21st-century eyes like yours and mine. When you turn to the first edition of Indiana Central University’s First Annual Catalogue: 1905, you don’t find language that comports with this prohibition – at least it is not immediately obvious. Instead, students are expected to cultivate “personal culture,” which the catalog declared to be “the true purposes of the student in college” in relation to essential standards of “manliness and womanliness.” (see pg. 13) These notions, in turn, pertained to expectations of propriety and good manners, which were reinforced in a variety of activities, ranging from mealtime behavior to the evening curfew to personal hygiene.

Such concepts were also loaded with meaning for the young men and young women who were part of the Temperance Movement, so it is quite possible that readers in the first decade of the 20th century would have read them as having a stronger Temperance emphasis than they do for readers in the 21st century. So much like the torch held up by an arm – which was the official emblem of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union well before it became part of the seal of ICC and later UIndy – it is not easy to say where one set of associations (WCTU) stops and the other (ICC) begins. It is quite possible that for some students the coincidence was mutually reinforcing. In other instances, there may have been students who reacted to Temperance restrictions during Prohibition.

Before and during Prohibition, the faculty of ICU were the arbiters of propriety and good manners. Accordingly, chapel attendance was monitored. Much was left unspecified as witnessed in the following statement from the section on Conduct in the First Catalogue (1905-06 academic year): “For a student to violate the rights of other students or the rules of good conduct, will subject him to private or public reproof, and if necessary, to suspension or expulsion as the faculty may decide.” (see pg. 13) We know that in subsequent years some students were caught playing cards, smoking, and presumably, there may have been alcohol violations as well. The final lines of the catalog under the category of “Government” piously assured readers: “Good conduct will always be rewarded. In fact, it has its own reward.”

In matters of room and board arrangements, parents were invited to provide specific “suggestions they may wish to make respecting their government.” This may have been prudential given the limited accommodations at the time the college opened in the fall of 1905. It makes it clear that the university did see themselves acting in loco parentis. In the beginning, at least, the restrictions of the neighborhood were separate from the laws of the state and the U.S. government.

In sum: there was a dual mandate – students were expected to be self-governing (voluntarily seeking virtue in matters moral), and if they displayed the absence of that ability, then college faculty would act to reassert the expectations for propriety, which overlapped with expectations associated with Temperance. The faculty reserved the right to withdraw “any student whose conduct or work was judged to be unsatisfactory.”

The governance of the university operated within the authority of the church. Indeed, the college was properly understood to be the “church’s business” at this juncture, so it is quite possible that all concerned presupposed that if all properties of the neighborhood – including Indiana Central University – were subject to this legal provision pertaining to property ownership, then those persons who were subject to “religious influences” of the faculty would follow those same rules of the church and the neighborhood.

Another wrinkle to consider is that the ages of the students in the Academy (preparatory school) and the college were not uniform in the ways that we think of cohorts of “the traditional college student” (ages 18-22). Some were teenagers, some were in their 20s, and a few students enrolled at ICU were in their 30s. By 1910, there were still only 20 houses in the neighborhood, but almost five times that many houses had been built by 1920 when the first residence halls were built. (The current number of houses was not achieved until after World War II.) Regardless of the population density, University Heights would have been “dry” (or white on the maps) beginning in 1904.

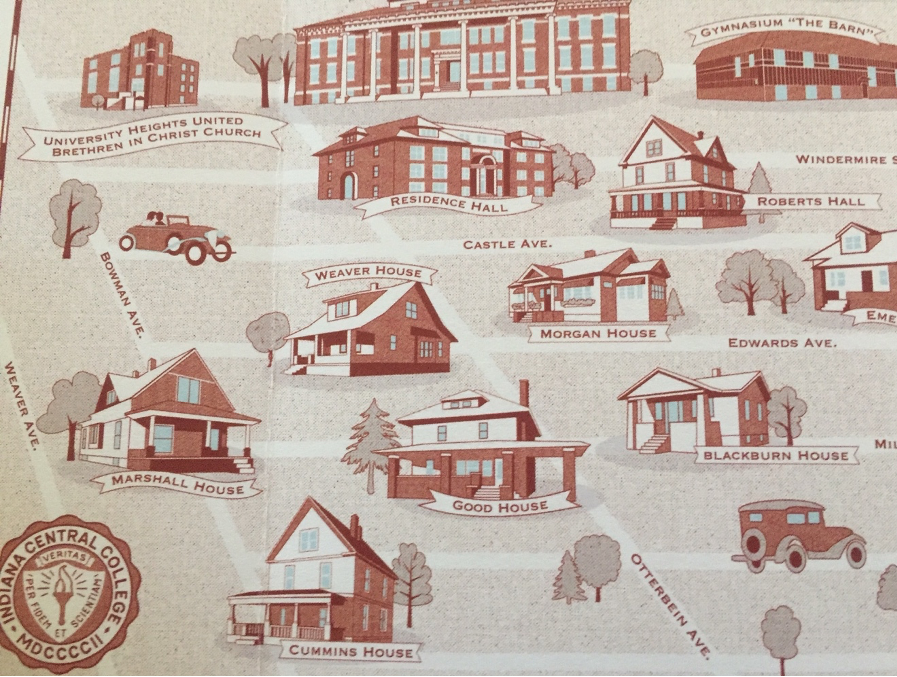

More than perhaps any other point in the university’s history, the ICC campus and the University Heights neighborhood would have had extensive overlap during this period. Beginning with the 1923 Oracle yearbook, there are photographs of faculty homes like “Good House” indicating that students were familiar with the neighborhood. Some students lived with faculty and others boarded with residents who were not affiliated with the college.

Even so, wherever rules for community exist, there are rulebreakers. And where rules are broken, there are stories to be told about the mischievous antics of those who operate outside the house rule.

Temperance had been around long enough that students would also know that there were plenty of satires about the hypocrisy of communities that adopted Temperance standards. Many of these students would have grown up reading Mark Twain’s novels written in the 1870s about growing up along the Mississippi River in Missouri near Cairo, Illinois. Twain’s tale about The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) includes satire of the “Temperance Tavern,” of which there were two in the community of St. Petersburg, Missouri, each of which had a backroom where alcohol was served.

Of course, there were no such establishments in University Heights, but there may have been “speakeasies” nearby, perhaps closer to Fountain Square. Some students probably knew where the local still was located somewhere along Lick Creek or amid the truck farms along South Meridian Street. Perhaps there were even residents in the neighborhood who made bathtub gin. Part of the student experience for any generation is to explore the world beyond the house rules. Most students would have needed little instruction about how to misbehave, but those who had inquiring minds may have sought inspiration from the fiction of Mark Twain among others.

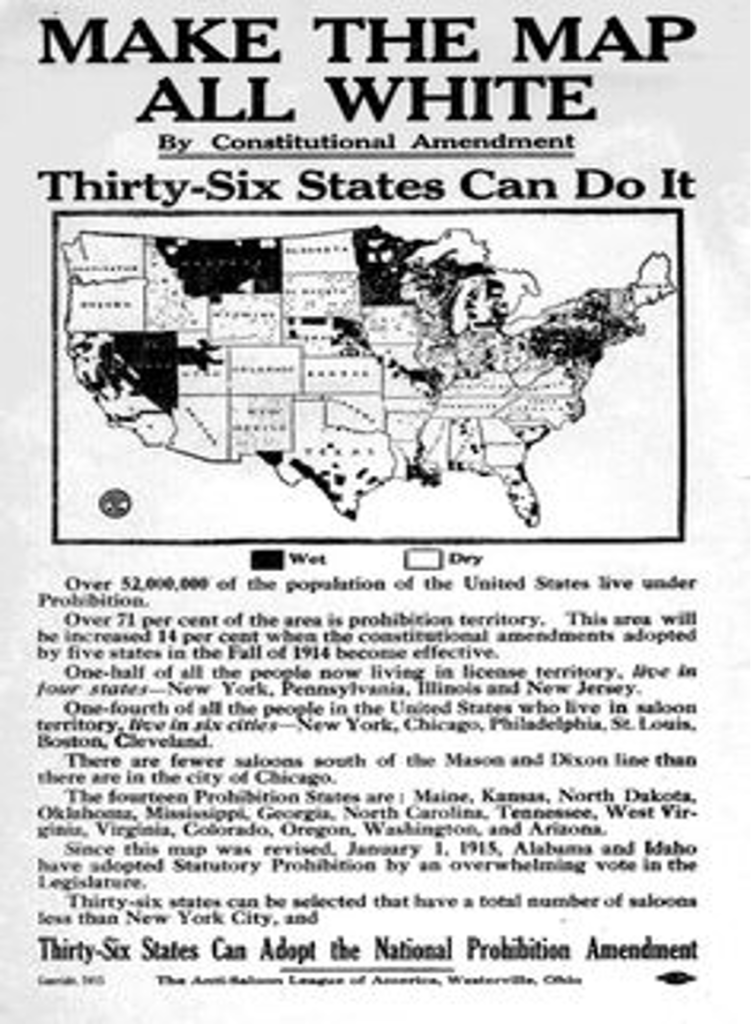

What may be funny to a child in a small town looks very different when located in the context of state laws and national regimes governed by the U. S. Constitution. Students at Indiana Central prior to 1920 would have had no doubt that the goal was not simply to uphold the Temperance tradition of abstinence but also to “make the map all white.”

The 1915 “Make the Map All White” poster (see above) may never have been seen by students on the ICC campus, but the statistics associated with the campaign put Indianapolis in the crosshairs of the effort to achieve Prohibition, and many of the students were raised in the small towns of Indiana. This war to achieve Prohibition of the sale and distribution of beverage alcohol was visibly rural vs. urban, with the cities named as “saloon territory.” Twenty more states enacted Prohibition laws over the next four years. And then, the objective was achieved at last. The decades-long effort to prohibit the sale and distribution of alcohol across the land had shifted from a form of placemaking to the gnarly tasks of “placekeeping.”

Student Engagement with Temperance

The first record of student engagement with Temperance I have been able to locate is from the student newspaper, The Reflector (1923-03-15: 1). The state president of the WCTU, Mrs. Stanley, spoke in chapel. The student editor opined that ICC students were “in hearty sympathy” with her work. This reference is much later than I expected to find, but the paucity of extant documents from the Office of the President (1905-1908) and the material culture of student life (there was no student newspaper until 1922) are challenges that cannot be overcome at present. We do know, however, that the WCTU was quite aggressive about their efforts to engage children, youth, and young adults to get them to sign the pledge to abstain from intoxicating beverages. Not surprisingly, speakers from one or the other Marion County “unions” sometimes served as speakers at Indiana Central’s Chapel events. Consider the following examples:

In 1930, the neighborhood “union” group of WCTU sponsored a Bible contest in the neighborhood that involved students at Indiana Central College. According to the January 17, 1930 issue of The Reflector, “George Barkley, of the speech department won the first of five silver medal contests being sponsored by the WCTU of the church. His selection was from [the Gospel of] John. . .” (One wonders if young Mr. Barkley took on the challenge of interpreting the gospel story of how Jesus turned water into wine at the marriage of Cana-in-Galilee described in John 2:1-11. While this is the most obvious focus, there are other possibilities. Regardless, in this incident we clearly see that Temperance movement leaders were cultivating youth and young adult leaders to be able to offer arguments to defend the cause of prohibition.) Regardless, questions persisted about whether the ethos of prohibition could be sustained despite the fact that speakers from the Indiana Anti-Saloon League visited campus regularly in 1930 and 1931 to cultivate support. Their unmistakable message was: “Prohibition has been secured. Let us keep it.”

The March 11, 1932 issue of The Reflector reported that a sophomore at the college, Miss Grace Adams, had been awarded the five-dollar prize offered by the Marion County WCTU for the best paper on prohibition written by Indiana Central College students. There were seven contestants. Adams was presented with the prize by Mrs. Felix T. McWhirter in the chapel program Friday, Feb. 26, when Mrs. McWhirter talked on the subject of Prohibition. The title of the winning essay by Adams is “Shall We Keep Prohibition?” (1932-03-11: 3) The presumptive answer of the paper, of course, was yes; the WCTU would not have awarded a prize for a paper that argued against prohibition.

At this point in the history of the college, the congregation of University Heights United Brethren Church was still meeting in the college building (now known as Good Hall). Technically, it was possible to refer to the WCTU as if it existed as a separate entity, and not part of the institution of Indiana Central College. On the other hand, if you were a student living in the neighborhood at the time, the extent of the overlap between the college and the church in terms of the composition of the neighborhood may have made it feel quite artificial. Part of the conundrum in determining the strength and weakness of the Temperance ethos in the neighborhood is the gradual differentiation that began to take place at Indiana Central College and in the University Heights neighborhood in the mid-1920s.

But when it came to President Good, no one had any doubt about where he stood on the matter. See, for example, the “President’s Message” in The Reflector published following the 1930 visit from WCTU leader Mrs. Elizabeth Stanley who once again spoke in chapel. On this occasion, President Good hammered home the point that the remarks by the WCTU leaders were “in line with the standards of this institution.”

What do we know about Prohibition Era Students?

One of the indirect effects of the student experience of higher education is the heightened awareness of different journeys of peers through encounters in dormitories, athletic contests, dining facilities, etc. When ICC’s enrollment census finally reached 350 in the fall of 1924, the students were jubilant. The article in The Reflector reported that this total comprised 100 students more than the previous year. The fact that 50 students were enrolled in the Academy (the preparatory school) was also reported, but all concerned understood that filling all 250 spaces in the residence halls for the first time said something important about the viability of campus social and intellectual life.

The ICC campus community had reached critical mass. At roughly the same time, the Board of Trustees announced the construction of another new residence hall. So the mood among students was optimistic. The growth in the number of students also brought about a dawning recognition of the broader characteristics of the student body, which was beginning to display more of a sense of self-awareness than had been the case during the two previous decades when the student census had been less stable.

Other than the classifications of freshman, sophomore, and upper-class ranks, church membership was the primary mode of classification reported by The Reflector in Vol. 4, Issue No. 2 (1924):

- United Brethren: 257

- Methodists: 24

- Christians: 16

- Presbyterians: 4

- Friends: 4

- Lutherans: 3

- Baptists: 3

- Holiness: 2

- Reformed: 2

The concluding clarification, “four did not report any church membership,” provides further indication of the overwhelmingly Protestant character of the student body that would have gathered for chapel three mornings a week. Based on cultural patterns found elsewhere in the Midwest in the late 19th century, the denominational identity most likely to have resisted the Temperance emphasis would have been the Lutherans, but that does not mean that those students did so. Indeed, we don’t have a basis for saying what, if any, convictions these students may have held regarding the use of alcohol as a beverage.

We do know that in 1923 one of the questions students discussed in The Reflector was how to balance the college’s established “traditions” – like the prohibition against smoking – with the increasingly “cosmopolitan” (yes, that is the actual word the writer used!) character of the student body. The article in question expressed the hope that everyone would figure out how to maintain the warm hospitality of the campus while upholding the tradition but offered no clear resolution for how to do so.

This kind of conundrum raises the question of whose “house rules” do we use where conflicts arise? With only 62 non-United Brethren students out of 350 total students, the college’s denominational affiliation remained the definitive demographic in 1924. That year students from United Brethren backgrounds comprised 80.6% of the total enrollment; the aggregate total actually was divided geographically according to the denominational regional conferences that were providing financial support to the college: White River (IN) 126; St. Joseph (IN) 70; Illinois 55; (Southern) Indiana 51; Wisconsin 7. The Registrar’s Office reported other states and territories represented in the student body: Michigan 4; Ohio 3; Kansas 1; Montana 1; and Puerto Rico 1.

One in five ICC students enrolled during the 1923-24 academic year were listed as living in Marion County and attending from their homes (an early cohort of “commuter students”). Presumably, some of these students lived in University Heights. Virtually all of the students who were from outside the state of Indiana were from United Brethren church backgrounds. Although the total number of students did increase over time, the year 1924 may have been the greatest density of United Brethren presence in the student body.

Meanwhile, over the next two decades, the proportion of ICC students who shared the UB background would decline further until settling out around one-third UB versus 2/3 non-UB members, although still predominately Protestant. I have to wonder at what point the effort to keep the map “all white” in University Heights began to feel like a losing cause because of the fact that Prohibition was not working in the ways that the ASL and WCTU had believed that it would. At this point, we simply do not have the kind of data and/or perspectives about the student experience to know when – or if – that was the case. What we do know, however, is that ICC students recognized the need to discuss the growing tensions surrounding Prohibition policies and practices.

An ICC Professor & Students Discuss What to Do about Prohibition

The topic of discussion at the October 18th evening gathering of the Christian Endeavor Society at Indiana Central College was Prohibition, which everyone recognized was becoming increasingly problematic. The year was 1931 – a little more than a quarter of a century after the college was founded and 11 years after Prohibition had started.

At the time of this meeting, the students and faculty who gathered on the first floor of the building we know today as Good Hall had no clue that the election the following year would mark a dramatic shift in public support that in turn led to the reversal of the 1920 enactment of Prohibition with the revocation of the Volstead Act, but that is to get ahead of the story. Based on the news report of the occasion, participants in this event recognized that prohibition was not working out the way many had thought it would. Thus the question: What shall be done with Prohibition?

Before I say more about that query, let’s pause for a moment to consider who initiated this discussion. The short answer is that it was student leadership. I bring this up because I remain impressed that student initiative is one of the neglected aspects of institutional storytelling at this university. In this instance, we can’t ignore the fact of the matter. Students made this happen.

The Christian Endeavor group at Indiana Central College was one of several student-led fellowship groups on campus in addition to the literary societies and athletic booster groups. The Christian Endeavor Society played a “cooperating” role with the two “Y” groups, the gender-specific groups which shared the same four-fold purpose: “The improvement of the spiritual, mental, social and physical condition” of the Young Men’s and Young Women’s Christian Associations.

President, Christian Endeavor Society, Indiana Central College, 1931-32

Whereas these Christian groups focused on fellowship, the leaders of Christian Endeavor took responsibility for creating opportunities for ICC students to explore important questions. In 1930-31, the president of the group was Paul Milhouse ’32 (a student pastor who later served as a bishop in the EUB/United Methodist Church). The person selected to lead the group in 1931-32 was Christine Dalton, a bright young woman from Muncie, Indiana. Ms. Dalton appears to have been greatly admired by her peers; she is described in the 1932 Oracle as being a “mastermind” for her campus leadership, and perhaps the editors had in mind the fact that she was the one who came up with the idea for the discussion of Prohibition that took place the previous fall.

This occasion is also the earliest evidence that I have found of a searching conversation between faculty and students on the campus of Indiana Central College about the problems associated with Prohibition. This does not mean that there were no such conversations before this event. Indeed, I strongly suspect there must have been informal activities. We simply do not have readily available records of such exchanges in the University’s archives or in other local history sources before 1931.

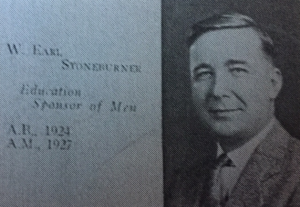

The speaker for the October meeting was Earl Stoneburner ’24, a young educator from Valparaiso, Indiana who had returned to his alma mater a couple of years before to teach courses for students preparing to be public school teachers. More about Prof. Stoneburner’s conversation with the students in due course, but first I should explain why I believe the Oct. 18th talk to the Christian Endeavor group was significant.

According to The Reflector, “Professor Stoneburner discussed the problem at length. ‘The prohibition problem can not be solved by the older men and women of today,’ he said, ‘but the young people who are now coming of age will be the ones who may be permitted to decide whether prohibition goes or stays. Education of the people to know the facts will bring about a safe decision.” (1931-10-23: 2-3)

This is a fascinating summary. Given that the speaker took plenty of time to talk about the issue in question, the ultimate conclusion that the newspaper reports is not so much a form of parent-like guidance as it is a kind of deference to the agency of the students as citizens whose challenge it is to wrestle down this matter. In 1931 did Christine Dalton and her peers perceive the conflict over Prohibition as intractable? And what does it mean for Professor Stoneburner to appeal to “the facts” as the basis for making safe decisions? Does he have in mind statistics of public health? Or is he merely preaching to the choir? Did he gesture at the stock answers of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, with which the students might already be familiar? Did he parrot the arguments of the Anti-Saloon League leadership at that time?

Or did Prof. Stoneburner discuss developments such as the May 1929 release of the National Commission on Law Observance and Enforcement (popularly called the Wickersham Commission) stating that “during Prohibition the per capita consumption of alcohol had actually increased 500 percent between 1921 and 1929, reversing a downward trend that had taken place between 1910 and 1920”? Prohibition appeared to have had the opposite effect on alcohol consumption than what the Temperance advocates had predicted. Finally, Prohibition posed unanticipated health risks. Bootleggers made alcohol with suspect ingredients, sometimes unwittingly poisoning themselves and/or their customers.

It is an irresistible temptation to speculate what questions Christian Dalton and her peers may have asked on such an occasion. Lay leadership was one of the strengths of the United Brethren Church, and the United Brethren had been talking about Temperance since the 1840s. Stoneburner and Dalton were laypersons. From the beginning, the United Brethren Church had maintained that alcohol could be used for medicinal purposes. The “Bone Dry” regulations pushed through the Indiana legislature in 1926 by the ASL in order to solve the problems of Prohibition enforcement exceeded the limits of the historic stances associated with the Wesleyan and United Brethren movements (see Temperance I & III discussed in MM #67). This may have been the point at which the ASL zealots began to lose the support of Indiana citizens, including ICC students. Indeed, it displays the kind of intemperance that we now associate with what (since the 1990s) has been known as the “culture wars” in the U.S.A.

Suppose the students had been talking about problems of race and class in one of their U.S. history classes? In 1924, the Ku Klux Klan was at the height of its influence in Indiana. Would one of these students have dared ask about the intersection of race and Prohibition? Or should we assume that a slogan like “make the map all-white” would only raise the eyebrows of students and faculty in the 21st century?

These are but a few of the questions we might want to ask about this particular event where ICC students had invited a professor to talk with them about “what to do about Prohibition.”

ICC & University Heights During Prohibition: Known Unknowns

I also think this brief article about the Christian Endeavor’s society meeting in October 1931 highlights what we don’t know about the student experience of Prohibition at ICC. I cannot offer a detailed list of these known unknowns, but there is plenty of room for enterprising students who might want to explore such an unplowed field.

- Before the fall of 1931, virtually all references that I have found in The Reflector newspaper and the Oracle yearbooks from this period imply that Temperance is the way forward, that Prohibition inscribes the ethos of the college. The following year, I see the dawning recognition that their community is not monolithic (see forthcoming MM#69). But as long as familiar figures like President Good – and before him Mother Roberts – are in view, it is possible to assume the Prohibition regime coincides with the house rules.

- Speaking of Mother Roberts, I have plenty of questions about the WCTU and ICC. For example, to what extent did the Temperance iconography intersect with the student culture of ICC? To take but the most obvious example, the torch which has been on all three of the seals of the university is strikingly similar to the upheld torch which was the official emblem of the WCTU. In one sense it’s hardly surprising because symbols of light, lamps, torches, and fire are all associated with higher education in both sacred and secular versions. When icons are used in the same ways, however, it is not unreasonable to assume a strong affinity between groups. Is that true in this instance?

- Finally, other than the absence of bars until the mid-1960s when Colonial Tavern Inn opened at 4343 Madison Avenue on the Southwest side of the University Heights neighborhood, we don’t have evidence of the extent to which Temperance shaped the culture of the neighborhood apart from what was happening on campus where most students lived. If creating a Temperance community was the first placemaking project to be launched other than the university, what have been the most powerful effects and (unintended) consequences? And what would count as evidence for making such judgments?

These are by no means the only questions that a thorough study of Temperance in University Heights might explore, and I freely admit they are not yet framed with the kind of precision that could yield meaningful evidence and data for analysis. They are simply questions that it appears no one has asked before now. But I think we should. After all, once upon a time, Temperance lived in University Heights, but regardless of how the house rules have changed, she has been one of our neighbors from the beginning.

The next issue (MM#69) will focus on what happened at Indiana Central after Prohibition ended.

As always, please feel free to share your own thoughts and responses with me at missionmatters@uindy.edu. In the meantime, don’t forget that UIndy’s mission matters!