Mission Matters #74: Reincorporating Stories of Black, Indigenous, & People of Color – part 2

Mission Matters #74

by Michael G. Cartwright

Vice President for University Mission

Reincorporating Stories of Black, Indigenous, & People of Color Stories – Pt. 2

“Remember the Alamo” (97-117) is one of my favorite essays in the book On Juneteenth, which explores a famous cinematic artifact of the saga of Texas peoplehood. Annette Gordon-Reed (hereafter AG-R) also uses this famous directive as a narrative context for exploring a wider range of memories – her own stories as a member of a Black family from the town of Conroe, as well as those of other people of color – with provocative results. The fifth essay of On Juneteenth raises searching questions about what we have chosen to remember and what we often elect to ignore

You may have heard of the song, “The Yellow Rose of Texas,” but if you are like me, you have never taken the time to learn about the various legends about the person who was at the heart of the story. AG-R did not know that much about the story until she listened to what family members told her that they had heard over the years. What she discovers – about the actual person, and the many stories told about Emily West — in the context of her personal quest to understand the mythic past of Texas is remarkable. Just in case you are reading the book, I won’t spoil the end of the story! However, it is a wonderful example of how a disciplined historian can sort out cultural myths and racist legends from historical fact while also paying attention to the role played by family history.

In MM#73, I called attention to one of the vexing absences that we wish could be replaced with knowledge of who BIPOC such as F. Jones were. I also introduced the annotated “timeline for reincorporating black, indigenous, and people of color” in the history of UIndy in the context of challenging faculty and staff to engage the challenge of recovering the memory of the first student of color to study at our university in 1916-1917.

In this second essay, I look at another vexing example – not of absence, but rather the public performance of Deep Are the Roots, a melodrama by a racially mixed troupe of student actors – that took place at the end of the fall semester in 1947 on the campus of Indiana Central College.

I. Melodramatic Perspectives at Indiana Central College ca. 1947

We know enough about what transpired on Nov. 30th and Dec. 2nd, 1947 to marvel at the fact that this theatrical performance was staged at this time and place. Indeed, it is even more fascinating when viewed in its historical context. The 1946-47 academic year was an uncertain season at Indiana Central College. The new president had taken some promising steps to lead the college in a more promising direction. The merger of the United Brethren Church with the Evangelical Church, which was consummated in the fall of 1946 with the creation of the EUB Church, had led some to think that it would be better to create one strong college than to have two weak institutions. After four decades of continuous debt, the college had finally been able to liquidate the debt, which meant that it could put away the rumors that the college would be merged with North Central College in Naperville, Illinois. In the end, though, ICC was given a second chance, and President I. Lynd Esch led the way forward, working with faculty, staff, and students in what amounted to a collective effort to re-found the college.

It is important to remember that the college was in such a penurious condition at the end of World War II, that there was very little infrastructure when Esch arrived. The post-war economic boom made it possible to move forward without taking unwarranted risks.The average number of graduating seniors in 1945 and 1946 was 50. That number jumped dramatically to more than 90 in 1947. In the spring of the 1947, President Esch received word that the North Central Accrediting Association had agreed to grant Indiana Central status as a liberal arts college. One of the conditions had been to expand the offerings in the liberal arts. Fortunately, there was already interest in the field of the performing arts, including theatre, and the students were ready to engage.

Ann Cory (Bretz) ’48 and her co-editor Albert H. Peters, Jr. chose to use a theatrical trope for the 1947 Oracle yearbook theme. They explained their focus with deliberately chosen melodramatic language. “In the history of all institutions there comes a time of crisis when those associated with it survey the past with pride in its achievements and love and respect for its ideals. They also anticipate the future with a courage and wisdom which will further those ideals. This year is such a crisis in the history of our world, our United States, and our college.” The sections of the yearbook featured a drama stage layout, including curtains and a stage with actors and other theatrical images.

We don’t know everything this pair from the class of 1948 had in mind, of course, but they saw themselves within the frame of a dramatic production “illustrating old and new.” They also saw the world’s problems – as matters of dramatic confrontation with the truth — on campus and beyond. The beginning of the Cold War and the continuing struggle with Jim Crow are two obvious concerns that likely have weighed heavily on their minds. The recent decisions not to merge the college followed quickly by the announcement that the college would be accredited by the North Central Association might have been focuses of concern for them, too. And they may even have thought about the Alpha Psi Omega production that year.

II. Black & White Indiana Central Students on Stage in 1947

Imagine what Florabelle Williams ’49, Mary Merritt ‘52 and their fellow students may have experienced when they stepped on stage for the first performance of Deep Are the Roots on November 30, 1947. We know exactly where it took place. In those days, virtually all events took place in Kephart Auditorium (1906-1962), the all-purpose space located on what is now the first and second floors of Good Hall, that served as the campus chapel as well as the location for public assemblies, and various performances ranging from chamber music recitals to dramas.

The one surviving artifact that we have from the production is a photograph that features the male lead character (who is black) with one of the female supporting actors (who is white). The character played by Roberta Good is holding the hand of the character played by Arthur Winn, Jr. That simple image of an interracial relationship between two college students represented some of the very things that the laws and customs of Jim Crow segregation were intended to keep from happening.

The ICC campus would have been fully aware of the fact that the play they were about to see performed was controversial. And my guess is that most of them knew that “social mixing” of the races had been viewed with disapproval at various times (particularly in 1922 and 1930) over the previous quarter of a century. Students and faculty alike would still have been looking to the “new president” I. Lynd Esch (assumed office in March 1947) for signs about what kinds of changes he favored.

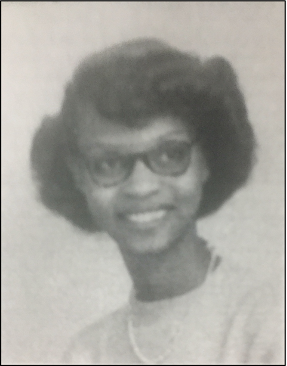

Only three of the ten characters were African-Americans, but black characters were at the center of the plot. Florabelle Williams [Wilson] ‘49 was playing the relatively minor – but for the purposes of the plot the surprisingly significant– role of Honey, the “thin, not unattractive Negro girl of twenty” who enters first. Florabelle’s initial gestures on stage are those of an upstairs maid in the Langford family’s home. But after putting the newspaper on the table for the Senator to read, she plucks one of the magnolia blossoms from the bowl and puts it in her hair. The stage directions read: “Then, smiling, her hand on her hip, she strikes a pose which she considers winning and flirtatious.”

Before a word is ever spoken, aspects of the conflict of roles that defines expectations in a racial society is introduced. And when Mary Merritt ’52 – who played the role Bella of the Senator’s maid – speaks the first words of dialogue, the audience enters a set of relationships between African-Americans that even in the absence of white people are afflicted by racial expectations and assumptions. As the play continues, the layered social binary – based on race – becomes more and more exposed to the audience.

I suspect that more than a few people would have been surprised to see Florabelle Williams playing the role of Honey Turner. In those days, Flora was rather shy and as a commuter student majoring in elementary education, she did not spend a lot of time on campus. Although she fit the physical characteristics called for in the script, the decision to cast her in this role was probably counterintuitive to the expectations of those who knew her. Precisely for that reason, however, it may have been an excellent choice since the Deep Are the Roots is all about upsetting expectations.

Arthur B. Winn, Jr., who played the role of the newly discharged Lieutenant Brett Charles, also fit the physical description of the young black man (23 years old) who returns to his home town in the Deep South only to find himself entangled in a swirl of expectations. Arnaud d’Asseau and James Gow, the team of playwrights, crafted Brett’s character through dialogue with minimum background information. Brett’s profile as a graduate of Fisk University (the Historically Black University in Nashville, Tennesse, founded by the Freedman’s Bureau) is only made explicit later in the play.

The most salient fact about Brett Charles is that he has returned home after serving during the war – where commanded men, fought in seven battles and was honored with the Distinguished Service Cross – to a hero’s welcome and all of the racial prejudices that define the world of Jim Crow.

In the end, the fact that as a war hero Brett Charles is due honor by the people of his hometown for his military service does not erase the fact that he is a Black man. As the play goes on, the presence of racist prejudice grows more menacing. After the parade is over, the Lieutenant causes offence when he speaks at the luncheon in his honor and denounces segregation as morally wrong. Even the simplest of actions – asking to check out a book at the local library without seeking permission from the Senator Langford’s family first—poses a threat to the town’s social order.

When Brett applies for funds to go to a civil rights conference in Atlanta, he is refused because of fears of what will come of such a gathering when white and black talk with one another outside the supervision of the guardians of white privilege. He is the focus of gossip, particularly after he is seen at night with a white woman (the Senator’s younger daughter Genevra), and when a watch is stolen in the second act, the suspicion quickly settles on him. The sheriff is contacted; a team of officers soon arrives to arrested him for theft.

Brett’s relationships with the Senator’s daughter “Nevvy” adds a further set of complications. These former childhood playmates – now grown into adults – find it difficult to define their relationships with one another amid the interracial relationship taboos. As the team of playwrights repeatedly stated, Deep Are the Roots is not about interracial marriage, but that is a concern that seems to animate the characters of the play. The fact that as children Genevra and Brett had enacted Shakespearean tragedies together – he played Iago and MacBeth; her roles were Desdemona and Lady MacBeth – seems rather improbable. However, this brief allusion to their past action roles reminds the audience of the possibilities and limits of the dramatic stage for discovering the truth about human relationships. In the end, she is “White” and he is “Black” – the racial hierarchy is determinative.

The playwrights used the genre of the melodrama to sharpen the vocational choice that lies before the central character. Brett can choose to continue his education at the University of Chicago where he has been accepted into a doctoral program – if he leaves his home in the south and goes to the north. Or he can stay home and take a position as the principal of the segregated school for Blacks in his hometown, which has recently become available. Alice, the young white woman and senator’s daughter with whom he had grown up in the plantation like community, presumes to tell him that he should go away to pursue his doctorate at the University of Chicago. “Brett, you’re a talented man. You owe it to yourself and – well, I’ll be quite selfish about it – you owe it to me, too.” (p. 64)

In response, Brett acknowledges that he owes her a debt but he asserts, “I have to pay that debt in my own fashion. I’m staying in the South, Miss Alice. If I can’t have the school – then I’ll pick cotton if I have to, And I’ll teach at night.” (p. 65) This former lieutenant’s longing for home and the alienation he feels upon the return to the community where he was born and raised are prevalent throughout the play.

While contemplating this choice, Brett recalls his experience of military service, which entailed helping the Black men under his command “believe they were fighting for a better world for themselves,” and he proudly declares that he had succeeded because he “was able to persuade them that this was their big chance to prove themselves.” (p. 64) With that context in view, Brett refuses to surrender his hard-won personal agency as a citizen in his home town – the freedom to decide – about what opportunities to pursue in the world of relationships that he has both inherited and is helping to create.

Deep Are the Roots, then, is a melodramatic play about learning to live in a social world that is defined by the possibilities of freedom from prejudice – the freedom to not “ride in the Jim Crow car” – a not so subtle allusion to the Supreme Court’s 1896 ruling in Plessy V. Ferguson that held that it was possible to impose segregation on blacks without violating their civil liberties under the 14th amendment to the constitution.

At several points in the three-act play, other characters weigh in on the matter. A Northern visitor to the Deep South named Howard Merrick opines: “Lieutenant, I can’t understand why in God’s name any Negro would stay here – why they don’t all just pick up and go North.” (p. 62) But as the authors make very clear – throughout the play – the spatial distribution of racist prejudice is not limited to southern precincts.

To their credit, the playwrights’ use of the “roots” metaphor is limited to a few brief references, principally in Act Two where the South is described:

“On top the flower is quite beautiful, full of grace and very delicate. But underneath are the roots, and occasionally you glimpse them, twisted and crossed as if choking one another. . .” (p. 96) The dialogue of the script is already saturated with Southern folkways, symbols of honor, and the trappings of racial privilege, and more than a dollop of mendacity.

I do not disagree with the critics of most recent performances of Deep Are the Roots; I too cringe at some of the dated dialogue and stilted allusions while reading the script of the play. At the same time, I also think this play provides one of the most effective metaphorical representations of the intricately entwined world of “Jim Crow” customs and practices that I have ever encountered. That it does so in part through its use of the image of the railroad car that brings Lieutenant Brett Charles home and will would take him away again (at the end of the play) makes it all the more ingenious as well as effective.

At several points, characters gesture at the supposition that the North is not racist and, each time, the play shows this to be a myth. Even the Pullman Car – a space of supposed autonomy where Lieutenant Brett Charles might seek safety in a private compartment until he reaches his destination of exile – is used in an understated way, to remind the audience that prejudice can be found wherever one might go in terrain of American life and culture. Long before advocates of “critical race theory” were making their case in the 1980s and UIndy students were chanting “Black Lives Matter” in the 21st century, the melodrama entitled Deep Are the Roots portrayed the intransigence of racism throughout the land.

III. Confronting the Truth: The Drama of Unmasking Racism

None of the characters who occupied the stage of the 1947 production of Deep Are the Roots – nine black and white people from the South and one person from the North – can see the whole of the matter. Indeed, everyone in the play has limited access to the truth about matters of race. That is part of the genius of this socially conscious melodrama by Arnaud D’Asseau and James Gow, writers who believed that “the playwright’s art must become action.” (Preface, xx)

In this particular case, they were trying the challenge the notion that the only dramatic role black people could play in American society was that of “the second-class citizen.” Theatrically speaking, these playwrights believed that they could change that situation by making “the thousands and thousands of Negro university graduates” the focus of dramatic agency. In other words, by putting black university graduates on stage, they wished to “a modest effort . . . to break the implicit conspiracy of silence that has reigned unbroken in the theatre for many years.” (xxiv). They understood that the fight for civil rights for the black American would proceed on many fronts; they believed “the very least that playwrights could do is to grant him literary equality.” (xxiv).

The force of this claim, when viewed in its historical context, is to call attention to the effects of segregation on the way Americans imagine themselves on the stage and in life. “Literary equality” is not the same as social equality, but it is a step toward realizing aspirations that in 1947 remained stifled due to the fact that Plessy V. Ferguson remained the law of the land, and Jim Crow still defined much of daily life. At the same time, this post-World War II melodrama repeatedly registers the prospect that the characters might yet be capable of facing up to the truth of what is the case with themselves, individually and collectively.

This pattern of melodramatic confrontations with the truth begins near the end of Act Two, when Honey Turner informs Senator Langford that she has found the missing heirloom watch. (The Senator had given to this family treasure – which according to tradition would have been given to the oldest biological son — to his older daughter’s fiancé in anticipation of the forthcoming marriage to Alice.)

This juxtaposition between truth and lies intensifies during Act Three, as multiple characters are forced to confront the truth about who they are and the social consequences of what they have done, as opposed to the wishful thinking that they have preferred until that point. Senator Langford’s two daughters who have recently returned to the Deep South after living in Washington, DC (supposedly “the north”) for many years, learn that relationships forged in their childhood cannot be re-engaged without incurring social consequences.

In particular, the younger daughter, Genevra (or “Nevvy”) realizes that she cannot enact her love for Brett on the social stage where the myth of white superiority dictates that a black man cannot marry a white woman without creating local scandal. Abruptly, Lieutenant Brett Charles discovers that for all the advantages that he has enjoyed thanks to the Langford’s family’s investment in his education, the Senator and his daughter Alice continue to believe that they should be able to control his life. This is no less true for the older generation, whose lives have been entwined for more than five decades. Bella (Brett’s mother) confronts the Senator about the truth of what “lily white men” have been doing to black women all her life; the Senator begins to see the mendacity in which he has immersed himself.

Members of the audience see characters on stage where “the whole truth” is exposed to view – like entangled roots that lie deep in the earth and extend well beyond hometown boundaries – and perhaps recognize some of their own moral blind spots and/or racial prejudice. They may or may not have found Genevra’s melodramatic confession of her attraction to Brett compelling: “I’m not ashamed. And I am telling the truth. And I may as well tell the whole truth.”

The Senator’s youngest daughter’s attempt to be honest with herself about the nature of her relationship with this Black man (the stage directions call for her to deliver her lines “slowly, painfully”) is highly dramatic. If well-acted, I can imagine that this moment could have stirred the students in the audience – as well as the company of actors on stage — at Indiana Central College. What is “the whole truth” that we/they have “got to hear” about the effects of Jim Crow segregation?

Former GIs like Robert “Bob” McBride ‘48 were ICC students in those years. These veterans had learned to operate within a more expansive set of role expectations; they had already faced up to the challenge of racial integration, at least to an extent. But for most of the audience, the play probably posed a social challenge – at least in terms of portraying “literary equality” African-American students – in provocative ways. Although I have yet to find an extended review of the play, we know that Deep Are the Roots also created a buzz in the city of Indianapolis. Reviewers for the Indianapolis Recorder as well as the morning and evening papers attended the play.

None of this should be taken to mean that the play brought about some kind of dramatic transformation on campus. It did not. But I would argue that staging such a play helped the college to achieve its aspirations to offer the kind of liberal arts education that enabled students to exercise responsible citizenship. Indiana Central students in the year 1947 may or may not have seen glimpses of themselves in the presumption, condescension, and immaturity of the characters portrayed on stage by their (black and white) peers. They might not have changed their minds about the regional character of racism. And it is all too possible that some of the students walked away from the performance still harboring explicitly racist imaginations. But what they would have seen on the stage of Kephart Auditorium at the end of the fall semester in 1947 was a socially embodied display of equality between black students and white students at Indiana Central College. ICC’s production by undergraduates pushed beyond “literary equality” to register greater expectations for Indiana Central.

IV. Reincorporating Deep Are the Roots – Lingering Questions

Given the foregoing summary of the play, it is frustrating to confront the absence of the kind of artifacts from the 1947 production of Deep Are the Roots that we have for many performing arts productions from the past century. For example, I have not found any copies of a program bulletin for either of the performances that took place on campus. On the other hand, we do know a fair bit about the cast and leadership associated with the play, thanks to the good work of student editors of The Reflector newspaper and press releases published in various newspapers in central Indiana. And, we know that the play received good reviews. Indeed, at the time, the Indianapolis Star reported the actor Carl Low’s review who judged it to be “the most outstanding amateur production I have seen in several years.”

First, we know who was in the cast. The young woman who played the Senator Langford’s daughter, Alice, was Roberta Good (Chaney) ’48, who was from Greenfield, Indiana. Arthur B. Winn, Jr. ‘53 played the central role of Lieutenant Brett Charles. Other students who were members of the cast were: Florabelle Williams (Wilson) ’49, who played the role of Honey Turner; M. Louise Dragoo (Barnett) ’50, who may have played the role of Genevra Langford; Mary Merritt (Rogers) ’52, who played the role of Brett’s mother Bella Charles; and Doug Butler, Jr.* who may have played the role of Senator Langford); These five students were all from Indianapolis. The remaining four minor characters were played by Harold Wright ‘53, who was from Columbus, Eugene Griffith*, from Lawrenceville, IL, Louis Brown ’49, from Decatur and William E. Morrett ’48 from Liberty.

We also know that the performance of the play was scheduled in conjunction with a reunion event for Alpha Psi Omega alumni to come back to campus to celebrate the theatre program. A reception was to be held following the second performance. The goal was to build support for theatre on campus. According to the Oracle yearbook, there were only four members of the theatre program’s honorary society but there were 45 students who had signed up to be “apprentices” to prepare for induction into Alpha Psi Omega.

These were the initiatives of the director of Deep Are the Roots, who served as Assistant Professor of Speech and Drama. Lester L. Schilling, Jr. (1920-1996) had two degrees at that point, a B. A. from Western Michigan and a M.S. Columbia University. During the two years that Schilling directed the theatre program (1946-48) at ICC, he took student groups to area churches to perform Christian dramas. At the end of the 1947-48 year, he left ICC for a 20-year career at Linfield College (Oregon) where he served as Professor of Drama, and along the way completed a doctorate from the University of Wisconsin. And after two decades at Linfield College, he spent the last half of his career teaching in the graduate program in theatre at Southwest Texas State University. (Why did Schilling leave? Was his contract not renewed? Or did he simply get a good offer and chose to leave? I think it probably was the latter.)

Who first had the idea for this particular production? I don’t think we know. It is possible that the 26-year-old director, who completed a Master’s degree at Columbia University shortly before he took the position at Indiana Central College, might have seen the play in New York City the previous year, when it premiered at the Fulton Theatre on Sept. 26, 1945. It is also possible that some of the students from Crispus Attucks who performed the play at Indiana Central might have learned about the play from musicians and artists who performed on Indiana Avenue in the period after World War II. And it is also possible that Les Schilling and the ICC students discovered that they had mutual interests in the world of theatre, especially dramatic works that challenges the racial stereotypes of the time.

What role did President Esch play? We don’t know. I think it is highly probable that he was consulted before anyone proceeded. And it is possible that he might have had questions of a tactical kind. But there are no records that I have seen that suggest that he was concerned about the prospect that the play would be staged on campus. Here is what is most striking to me. The play was launched at a time that Indiana Central College was – for all practical purposes – in the midst of refounding. The fact that a controversial play would be produced at this time is quite striking. This was not a president and faculty who were so cautious that they were playing it safe in dealing with Jim Crow!

What role did the segregated high school of Indianapolis play in building the capacity of Indiana Central College’s performing arts programming in the years after World War II? This is a question that dawned on me as I took the measure of the poverty of the situation at ICC that faced I. Lynd Esch faced when he arrived in 1945 and what transpired over the next 30 months until Deep Are the Roots was performed. I don’t think faculty and staff at UIndy have registered the significance of the education at Crispus Attucks High School that Alvin Winn, Jr. ‘53, Florabelle Williams Wilson ’49, and Mary Merritt (Rogers) ’52, brought to the project of staging a racially integrated cast in the fall of 1947 at Indiana Central College.

In the next issue of Mission Matters, I will discuss this part of the story. This is an aspect of the university’s intellectual heritage that, as far as I can see, has gone unexplored until now. If we are going to succeed in our current efforts to reincorporate BIPOC into the institutional memory of the university, we must remind ourselves of some of the things that happened in the city of Indianapolis before Florabelle Williams Wilson ’49 and her peers stepped on the stage at ICC. For that we must drive down memory lane through the segregated world of Jim Crow on Indiana Avenue until we reach the corner of 12th Street and Martin Luther King, Jr. Blvd. That is the part of the story I will try to tell in Mission Matters #75.

(Note: The * indicates there is no record of graduation from ICC.)