Mission Matters #67 – Founding a Temperance Community in University Heights

By Michael G. Cartwright, Vice President for University Mission and Associate Professor of Philosophy & Religion

This year we are exploring marks of excellence that can be discerned in the past and present of our institution. Virtues are displayed in the context of practices and social relationships, they reflect moral traditions, they are embodied by exemplars, and they are sustained by institutions such as universities. In MM #66, I introduced the topic of temperance. This essay focuses on the founders’ efforts to create a temperance community in University Heights.

One of the greatest obstacles to grasping the aspirations of the founders of Indiana Central University may be our inability to set aside our sense of superiority in knowing that efforts to forbid the sale of alcohol were bound to fail. We know how history turned out. Prohibition failed. The founders did not know that would be the case. President J. T. Roberts and Rev. Alva Button Roberts were social progressives – in their time, at least; they believed that it was not only possible to improve on the status quo, but that the betterment of society depended on their success.

Let’s begin in the middle — with what is most widely known — and that is that all properties that were purchased in the neighborhood between 1904 and 1920 were governed by the “Temperance Clause” that was the centerpiece of the University Heights neighborhood covenant (aka the “deed record”) filed for each of the properties in “Mr. William Elder’s Subdivision of University Heights” neighborhood.

“This conveyance is made subject to the condition . . . that the grantee, his heirs, lessees or assigns or any occupant of said real estate, shall not have the right to manufacture, sell or barter any spirituous, vinous, malt or other intoxicating liquor as a beverage on said real estate and shall have a right to enforce these provisions of this deed by proper, legal or equitable proceeds.” (Emphasis mine, See Marion County deed record #403, University Heights, June 26, 1906)

We know that the United Brethren in Christ Church specified as part of its negotiations with William Elder that this “Temperance Clause” should be inserted in the deeds. This was not unusual for this particular denomination. Similar language was inserted in the deeds for properties purchased from the Philomath College (near Eugene, Oregon) in 1867 and three decades later the Huntington Land Association for Central College in Huntington in 1896. As a mechanism for raising money, this kind of provision was commonly used. Depending on location, the addition of the Temperance Clause might be an attractive provision for prospective buyers.

In any event, this reflected the United Brethren Church’s long-held moral stance against beverage alcohol: “The distilling, vending, and use of ardent spirits as a beverage, shall and is hereby forbidden throughout our society; and should any preacher, exhorter, leader, or layman, be engaged distilling, vending, or using ardent spirits as a beverage, he shall be accountable to the class, the quarterly, or Annual Conference to which he belongs. . . .And if all friendly admonitions fail, such offending person or persons shall be expelled from the same; provided however that this rule shall not be construed as to prevent druggists and others from vending or using it for medications and mechanical purposes.” (1849 Book of Discipline). United Brethren were less conflicted about Temperance than their moral crusades against Slavery and Secret Societies. In fact, for many members, the three moral commitments were often intertwined.

The United Brethren Church’s Discipline at the time that the University Heights Neighborhood was founded reflected patterns of adaptation. The initial statement from the 1840s and the concluding exceptions remained except for the replacement of the words “ardent spirits” — which had taken on a restricted use for distilled beverages for a more inclusive “intoxicating drinks.” The primary change was in the awareness of United Brethren of the ways their own property usage and business partnerships put them in the position of moral compromise. United Brethren were more middle class and upper-middle class. They owned businesses, had financial investments, owned property, and were incorporated in a variety of ways.

Accordingly, in the first decade of the 20th century, the Temperance statements included a provision that forbid members from “renting and leasing of property to be used for the manufacture or sale of such drinks. Also, the signing of petitions for granting license, or the entertaining of bondsmen for persons engaging in the traffic of intoxicating drinks, are strictly prohibited. . .” In sum: at the time that University Heights was founded, the church had a moral rule that specified that business endeavors needed to spell out such restrictions so that the membership of the United Brethren would not find themselves contributing to a problem.

The fact that the Colonial Inn Tavern, which opened in the 1960s, was located on the Southwestern corner of University Heights, is the consequence of such land-use policies, not merely happenstance. It is but one feature of placemaking. To grasp other aspects, we need to back up and review the origins and development of the Temperance movement, which not only influenced the founders of the United Brethren at the turn of the 19th century but the founders of Indiana Central University a hundred years later.

Nineteenth-Century Temperance Movement

By the time the founders of ICU set out to found the community of University Heights, temperance leaders had been organizing societies, fraternal organizations, and communities of one kind or another for more than a half-century. The limited availability of drinking water in colonial America was a key variable in the consumption of alcohol. In that circumstance, temperance was a practical concern in which public health concerns combined with moral reservations about inebriation. Many of the early temperance leaders imagined themselves replacing something evil (alcohol) with something pure and refreshing (cold water) not so much in the fashion of classical statuary, but rather as brigades carrying buckets of cold water to thirsty souls.

By the time the founders of ICU set out to found the community of University Heights, temperance leaders had been organizing societies, fraternal organizations, and communities of one kind or another for more than a half-century. The limited availability of drinking water in colonial America was a key variable in the consumption of alcohol. In that circumstance, temperance was a practical concern in which public health concerns combined with moral reservations about inebriation. Many of the early temperance leaders imagined themselves replacing something evil (alcohol) with something pure and refreshing (cold water) not so much in the fashion of classical statuary, but rather as brigades carrying buckets of cold water to thirsty souls.

Religious scruples about alcohol coexisted with practical concerns. In the 1740s, figures like John Wesley and “the people called Methodists” advocated abstinence from “spiritous liquors” except for medicinal purposes, but still drank wine or even beer or ale. For the sake of clarity, let’s call this pattern Temperance I, a disciplined attempt to curb alcohol abuse in a class-based society. The practice of total abstinence – dubbed “Teetotalism” – came along later and was closely associated with the Wesleyan or Methodist Movement. Leaders of the United Brethren shared these sensibilities.

But there were other variations. In the Jacksonian era, there were plenty of examples of “the self-made man” who banded together to reinforce habits of thrift and hard work. They helped one another out, provided insurance benefits, etc. In the 1850s, a masonic group or “secret society” of men formed who called themselves the “Sons of Temperance.” In addition to fraternal fellowship, they existed for the twofold purpose of supporting temperance endeavors and (less visibly) helping to facilitate the Underground Railroad in southern states. This is Temperance II.

Pious fellows that they were, these temperance brotherhoods gave their “worthy patriarchs” a medal to wear that had had an open book (Bible?) on one side and a fountain on the other side. Their version of the masonic triangle against a blazing sun proclaimed the words LOVE, PURITY, and FIDELITY. The banner across the top conveyed the double-edged message “Welcome to the Worthy.”

Pious fellows that they were, these temperance brotherhoods gave their “worthy patriarchs” a medal to wear that had had an open book (Bible?) on one side and a fountain on the other side. Their version of the masonic triangle against a blazing sun proclaimed the words LOVE, PURITY, and FIDELITY. The banner across the top conveyed the double-edged message “Welcome to the Worthy.”

Turns out that it was precisely such features of fraternity based on worthiness that made ordinary religious folks uneasy. The idea of living in small-town communities where hospitality is offered to neighbors based on secular notions of worthiness rankled pietistic Protestants. Not every man IS “worthy” because some men engage in unworthy behaviors (slavery for instance; drunkenness for another). The United Brethren in Christ Church, which claimed a German-speaking Pietist heritage that upheld a belief in Christian unity that was earnestly unsectarian and prided themselves in being unpartische (unpartisan), objecting to political favoritism as being un-American. This is Temperance III.

In certain respects, the United Brethren had much in common with this fraternal group, but they spoke different languages of affiliation and had different symbols of equality. The “Sons of Temperance” only had one level of secrecy and that was (it appears in retrospect) to hide their anti-slavery activities, but the United Brethren determined (misheard?) that this was a violation of the kind of Christian fellowship that should be mediated solely by one’s relationship with Jesus Christ. And so the United Brethren had a rule against someone being a member of the Church and a “secret society.” In retrospect, it is hard not to think of this as smallminded, but we mistake their moral objection if we fail to register the egalitarian ethos they were trying to uphold.

Most commentators agree that the Civil War disrupted these patterns of religious, secular, and masonic temperance groups. During Reconstruction, new patterns of leadership emerge. Women were no longer content to assist men in their efforts. The creation of the National Prohibition Party in 1869 – as a third player in regional and national politics – divided the temperance movement between pragmatists who were willing to work in a two-party system and zealots who sought to reform the nation root and branch. This was happening, of course, at a time when larger numbers of European immigrants were coming to the U.S., many of whom brought with them folkways that involved imbibing alcoholic beverages.

Before long, a new kind of temperance (non-Prohibitionist) developed in the Midwest, which sought to reinvent the moral suasion approach that had been prevalent in the antebellum period. During the 1870s, an Irish evangelist named Rev. Francis Murphy stirred enthusiasm for abstinence in the context of an evangelical revival. There was no attempt to change laws or prohibit the sale of alcohol as such, only to engage the need for social reform in the lives of each person. “Murphyism,” as it came to be known, is Temperance IV.

For Murphy and company, abstinence was an indicator of religious health or salvation, and as such, the act was entirely voluntary. Persons who signed Murphy’s pledge wore “blue ribbons” to indicate they were voluntary abstainers. Murphy achieved a great following among middle-class professionals and civic leaders in Pittsburgh and the Ohio River Valley, including among members of the United Brethren Church.

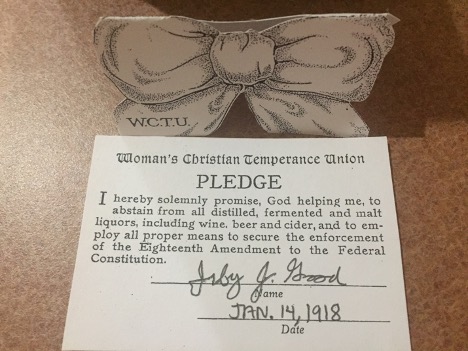

This “moral suasion” approach did not produce consistency, however. Those who wanted a permanent solution turned to the effort to prohibit the sale of alcohol. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) carried the crusade forward on behalf of the “women’s sphere” with the explicit goal of prohibiting the sale of alcohol. The Anti-Saloon League organized the men and put forward social legislation in state and national spheres.

The WCTU and the Origins of the Temperance Crusade

The WCTU perceived alcohol as both the root cause and consequence of all the other major social problems. The constitution of the WCTU called for “the entire prohibition of the manufacture and sale of intoxicating liquors as a beverage.” This was but one of a cluster of social reform issues that concerned these women crusaders. Others included child labor, prostitution, public health, sanitation, and international peace. As the movement grew, voting rights for [white] women also became a strong emphasis. Local chapters, known as ‘unions’, were largely autonomous, though linked to state and national headquarters. [Francis] Willard pushed for the ‘Home Protection’ ballot, arguing that women, being the morally superior sex, needed the vote in order to act as ‘citizen-mothers’ and protect their homes and cure society’s ills. At a time when suffragists were viewed as radicals and alienated most American women, the WCTU offered a more traditionally feminine and ‘appropriate’ organization for women to join.

The storied rise of the WCTU began “the Women’s Crusade” that swept through small towns of Ohio in 1874, and the most beloved story of all was about what took place in the town of Washington C.H., Ohio at Christmastime in 1873. This community had already been the site of temperance activities for several decades going back to 1840. The Civil War interrupted the quest to rid the community of alcohol. When Dio Lewis, a temperance lecturer who had been raised there, came back home in Dec. 1873 to visit during one of his lecture tours, the nostalgia for the good old days combined with his eloquent exhortation on womanliness, resulting in the re-launch of the effort to rid their community of alcohol, which took the form of saloons, where men went to indulge their thirsts for distilled spirits as well as beer and wine.

On Christmas Eve 1873, Dio Lewis laid out his strategy for achieving greater results in eradicating the evils of beverage alcohol. The next morning, he met with a group of community leaders. As the narrator melodramatically told the story, “he enlarged upon these details until the hearts of his auditors were trembling with eagerness to try the same methods for the protection of their own homes.” (*See Carpenter citation in bibliography notes below)

The women appealed to the owners of local saloons to stop selling alcohol: “Knowing, as we do, the fearful effects of intoxicating drinks, we . . . appeal to you to desist from ruinous traffic, that our husbands, brothers, and especially our sons, be no longer exposed to this terrible temptation, and that we may no longer see them led into those paths which go down to sin and bring both soul and body to destruction. We appeal to the better instincts of your hearts, in the name of desolated homes, blasted hopes, ruined lives, widowed hearts; for the honor of our community, for our prosperity, for our happiness, for our good name as a town; in the name of God, . . . we implore you, to cleanse yourselves from this heinous sin and place yourselves in the ranks of those who are striving to elevate and ennoble themselves and their fellow-men; and to this, we ask you to pledge yourselves.” (*See Carpenter citation)

The women of Washington Court House and Hillsboro and other small towns in Ohio were willing to be arrested for this righteous cause, and their husbands convened in church for all-day prayer vigils while their wives were engaged in visible displays of conflict with the social evils of local drugstores and beer gardens and the odd saloon. If the owner of the business in question did not comply with their demands, then additional social pressures were brought to bear. Indeed, part of the strategy was to publicly shame business owners – Charles Passmore, Charlie Beck, and James Sullivan – until they surrendered to the pressure and stopped selling beer, wine, and spiritous liquors. “We, the physicians of Washington and Fayette County, do hereby agree to prescribe intoxicating liquors only in extreme cases, and wherein our judgment no other remedy will do.” (48)

And significantly, there was a pledge that all property holders in the community were to sign: “Believing it to be in the interest of our town and county, that intemperance be forever excluded from them, we, the undersigned property holders of Washington and Fayette county, do hereby agree and pledge ourselves not to lease or rent any property to be used for sale of intoxicating drinks as a beverage, so as to clearly prohibit the sale of such drinks by any person whatsoever.” (48) This became the model for other communities to use as the Women’s Crusade spread through the Midwest and beyond. To borrow a title from the chapter that gathered newspaper accounts of the 1873 crusade – “Ourselves as Others Saw Us” – the events were craftily cast as a dramatic spectacle.

Indeed, everyone in the town was urged to join this moral revival, the participatory sacrament of which was to “take the pledge” of abstinence from alcohol. In some contexts, pledges were for a period of years, but in many instances, it was assumed that the pledge was a lifetime commitment, and depending on when and where one lived or first “pledged” abstinence, there might be a mixed set of patterns. Participation in the Temperance movement was (technically) “voluntary” and the effort to prohibit alcohol was a matter of self-government; the two went together like hand in glove.

Meanwhile, the congregations of Lutherans and Catholics in the town of Washington C. H., Ohio stoutly opposed the Crusade that launched the WCTU. Mrs. W. G. Carpenter’s account of the Crusade at Washington C. H. discounts these protestations by priests, pastors, and lay leaders as errant attempts by immigrant communities (Irish, German, etc.) who were not part of the “true church.”

And when opponents of the Crusade attempted to chide the women for choosing to step outside their proper place in the home, the retort was that if men of the town were not going to police disorder, then it was necessary for the “woman’s sphere” to be extended to encompass the community. Indeed, part of the appeal of this dramatic spectacle was to encircle the community with the protective embrace of maternal care and thereby restore the social good which had been usurped by the evils of beverage alcohol. The maternal figure of Temperance re-oriented communities around the virtues of the home and reminded neighbors that civic purpose was to secure the well-being of all.

The women in the WCTU saga of “the Crusade at Washington Court House” were depicted as praying quietly at the saloon in a way that is deeply affecting. They earnestly believed that what they were doing was a form of moral persuasion; public shaming was a tactic that they used where recalcitrant saloon operators “resisted persuasion.” Any displays of physical force that occurred in the Ohio Women’s Crusades involved men. Indeed, in one or two instances the owners of the drinking establishments actually take up the ax and destroy the whisky barrels themselves!

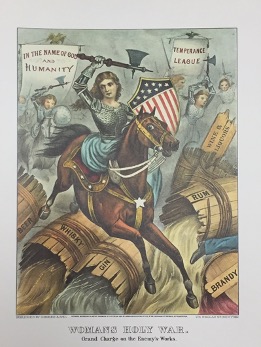

So the image of the women engaging in “Holy War” is a visual paradox. The iconic armed woman riding a steed, looking very much like St. George slaying the Dragon, is a dramatic externalization of a kind of spiritual warfare that was conducted with weapons of meek and humble pleading. And oftentimes, the frank demands of the women were communicated by their husbands who were also part of the organizational matrix. The theatrical displays associated with the Crusade were carefully staged. Part of the overall strategy was to put the “wets” in the position of doing something profoundly countercultural, namely to physically remove women, which reinforced the claim that they were engaged in practices that undermined the sanctity of the home and family.

So the image of the women engaging in “Holy War” is a visual paradox. The iconic armed woman riding a steed, looking very much like St. George slaying the Dragon, is a dramatic externalization of a kind of spiritual warfare that was conducted with weapons of meek and humble pleading. And oftentimes, the frank demands of the women were communicated by their husbands who were also part of the organizational matrix. The theatrical displays associated with the Crusade were carefully staged. Part of the overall strategy was to put the “wets” in the position of doing something profoundly countercultural, namely to physically remove women, which reinforced the claim that they were engaged in practices that undermined the sanctity of the home and family.

The self-described Crusaders of the WCTU were quite adept at telling their story (see partial list at the end), and after the 18th Amendment to the Constitution was passed, the saga of the Women’s Crusade was narrated as the fulfillment of prophecy. Apologists for the movement saw the women as progressive patriots.

Meanwhile, the Anti-Saloon League (ASL) partnered with the WCTU to carry out a new kind of pressure politics. There was nothing paradoxical about the ASL’s gender roles and identity. They played political hardball. Founded in 1893, the motto of the ASL was “The Saloon Must Go.” These men worked to unify public anti-alcohol sentiment, enforce existing temperance laws, and enact further anti-alcohol legislation. The ASL quickly gained power as a non-partisan organization that focused on a single issue – making temperance public policy. Indeed, they invented “pressure politics.”

With branches across the United States, the ASL worked with [mostly Protestant] churches to marshal resources for the prohibition fight. After two decades of work, ASL’s leadership determined to press for prohibition. Building on the mobilization for the Great War – which entailed great sacrifice on the part of citizens – the ASL exploited patriotic fervor in wartime to persuade Americans to support constitutional prohibition. By 1916, the group succeeded in electing the two-thirds majorities necessary in both houses of Congress to initiate what became the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

What Models for a Temperance Community Existed?

To understand what the founders were trying to do in University Heights, I think it helps to keep in mind the different streams of the temperance movement. Like other United Brethren, the founders of ICU tended to think of their advocacy of temperance as a constitutive feature of their Christian identity. They were far from lukewarm in their advocacy. Bishop George M. Mathews, who presided at the National Convention of the Anti-Saloon League in 1906, also served as chair of the Board of Trustees at Indiana Central University. Rev. Alva Button Roberts was a member of the WCTU for at least a half-century, and shortly before becoming President of Indiana Central University, her husband J. T. Roberts received a doctoral degree from American Temperance University. These are but the most obvious connections to mention.

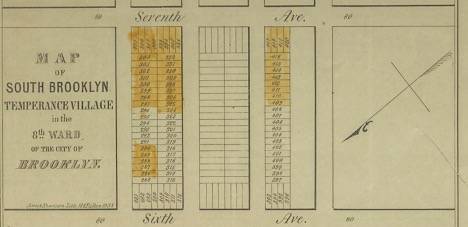

Efforts to create “temperance communities” began in New York in the 1850s (see map below), and continued throughout the 19th century. University Heights would have been founded at the tail end of that trend, just as the ASL and WCTU began to emphasize the “local option” movement. Indeed, in 1908, the State of Indiana passed a law making it possible for counties to prohibit the sale of alcohol. Soon more than 70 of the 92 counties in the Hoosier state had adopted those provisions. Marion County never did. Fifteen years later, in 1923, the City of Indianapolis annexed University Heights, which altered the legal code. Although that did not nullify the temperance clause, it did limit its applicability. Perhaps the primary effect was local disinterest in having bars adjacent to University Heights. It is quite possible that folks in University Heights never had displays of WCTU Crusades, but we know several leaders were involved in the WCTU and the ASL. Indeed, Pres. Good was a lifelong “dry” advocate.

On one hand, a temperance community was supposed to be a place where wholesome influences prevailed. The 19th-century images of the “Tree of Life” and the “Tree of Intemperance” offered imagery of success and failure. A thriving community was imagined as a neighborhood with houses and picket fences centered around a healthy tree bearing the fruit of the spirit; where the mother is waiting at the door and the morally upright husband (wearing a top hat like Abe Lincoln) is met at the gate by a daughter while the son is playing with the dog.

On the other hand, a temperance community was a site of activity. The women of the community were imagined to be members of the WCTU. We know that a “union” existed in University Heights as late as the 1920s. “Mother Roberts” probably helped to found that group. And no doubt, she did her part by encouraging students to “take the pledge” to abstain from alcohol, thereby matching the standards of the neighborhood to which residents had already agreed. Meanwhile, the rallies put on by the WCTU featured rousing choruses that imagined the transformation of the land by those who wielded the swords of civic purpose.

The men of a temperance community were supposed to be engaged in the political process, extending the sphere of “dry” territory, pushing back the tide of the “wets” to make the world a better place. And where a community was founded in the vicinity of a college, then the beneficent sphere of righteousness would extend to encompass the campus, lending its wholesome influence to the students who were fortunate enough to live in a neighborhood defined by the cause of temperance. But that would not have exhausted the hopes of the founders of University Heights. They would have also imagined that the students of Indiana Central University would have taken the pledge of abstinence and taken on roles – appropriate to their gender – as figures of “manliness” and womanly leadership in the moral crusade.

In addition to the work of the WCTU, there were other influences that the United Brethren founders of the university would have had in mind. The first place on the list would have been Otterbein University, which was located in Westerville, Ohio (near Columbus), which also became the headquarters of the National Anti-Saloon League in 1909. Otterbein had been founded on “the Oberlin model” of an independent intentional community that set its own moral rules, combined with the egalitarian hope (which often turned out to be little more than wishful thinking) that by dint of manual labor, young men and women could work their way through college. Otterbein also provided the primary model of what it meant for United Brethren to found a coeducational “church college” shaped by participation in the moral crusades against slavery, beverage alcohol, and secret societies (freemasons).

Other examples that appear to have been in view for the founders of Indiana Central University were the planned “temperance community” developments in various places in the country. The so-called “National Prohibition Park” in the community of Westerleigh (on Staten Island) and American Temperance University in Harriman, Tennessee are two of the best known of these “settlements that were planned, financed, and populated by the temperance movement of the late 19th century.” Both imagined colleges as part of the community. The experiment known as American Temperance University was founded in 1893 and had failed by 1908, but the New York venture has had more lasting effects in the context of the neighborhood’s robust sense of community (more on that in MM#70). On the other hand, Westerville, Ohio, did not permit beverage alcohol until the early years of the 21st century, and as recently as 2018 the community advertised its historic districts as “the war engine of prohibition.”

Imagining the Temperance Community as Placemaking

At the risk of committing the sin of anachronism, moral crusades are often about placemaking if not always about “placekeeping” as such. And this was vividly the case with respect to the temperance and prohibition movements, even in instances where crusades failed. But these were also influenced by the other “great causes” of the 19th century. In the case of the struggle to abolish slavery, the conflict was sectional. Slavery was and was not permitted in particular states of the United States, and where slavery was technically outlawed, as in Indiana, there were laws excluding Blacks from residence and little or no protections for free Blacks from the Fugitive Slave laws. Exclusion is a powerful form of placemaking.

The WCTU formed an alliance with the Anti-Saloon League between 1895 and 1920, with the vision to drive out “the wets” and make the country “all dry.” They thought of themselves as universalists in spirit, albeit in the spirit of “penitence, purity, and consecration.” According to Katherine Lent Stevenson, the white-ribbon bow, the official badge of the WCTU, was “particularly appropriate . . . its white the inclusiveness – no color because combining all colors.” Wherever WCTU leaders went, they distributed the white ribbon, tied into little bows, and placed upon new members. The national organization prided itself on the number of “unions” or chapters that were displayed on the maps of the USA.

But the color white also was used in more imperial ways, as we see with the WCTU Temperance hymn “Make the Map All White.”

Oh, comrade have you heard the glorious word that’s going round?

There’ll very soon be no saloon on all Columbia’s ground.

There’s a wave of Prohibition rolling up from ev’ry strand

And all the states it inundates, straightway becomes “dry land”

By city, state or county or by township or by town,

Just let the people have a chance — we’ll vote the dram shops down.

Till we make the map white, Till we make the map all white,

We’ll work for Prohibition Till we make the map all white.

The distillery, the brewery, and the winery all must go:

Saloons can stay no longer, when the people have said “NO”.

So we’ll sing them out, and vote them out, and educate them out.

We’ll talk them out and vote them out and leg them out,

We’ll agitate and organize and surely win the fight

For we’ll work for Prohibition, Till we make the map all white,

Till we make the map all white, Till we make the map all white,

We’ll work for Prohibition Till we make the map all white.

More often than not, the placemaking social imaginary that was in view was both the nation writ small and the neighborhood writ large.

Voting – initially by men alone, but after the 19th amendment also exercised by women — was the unit of moral action to be enacted “by city, state or county or by township or by town . . .” And the intended duration of this crusade was emphatic. The moral crusade would not stop until the map was “all white” (see lyrics to the hymn). The Anti-Saloon League invented single-issue politics, developing highly effective techniques for getting individual politicians elected – of either party — who supported the cause. While members of the WCTU may have continued to sing the song “Make the Map All White” and the ASL published thousands of fliers, pamphlets, songs, stories, cartoons, dramas, magazines, and newspapers, the righteousness of the cause was not always convincing. Indeed, Prohibition was repealed in 1933, and the map was no longer “all white.” But the Women’s Christian Temperance Union still exists!

Then and now, the WCTU believed temperance was a goal that must be national and international in scope. They created programs and magazines to reach out to children and youth. In some instances, such as the Little Cold Water Girl Fountain fundraising campaign, they caught the imagination of their constituency. The goal was to create public fountains throughout the world to provide “pure drinking water” as an alternative to liquor. The goal of this particular initiative was to have 350,000 children from dozens of countries sign abstinence pledges. Concurrently, children donated pennies and nickels for a decorative drinking fountain that would be displayed at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. They raised $3,000 to commission George Wade (1853–1933) to create “The Fountain Girl” aka the Frances Willard Fountain.

One can imagine WCTU members in University Heights participating in such efforts. No doubt, Mother Roberts encouraged boys and girls as well as ICU students to sign the pledge committing themselves to abstain from alcohol. But you will find no Temperance Fountain on the University of Indianapolis campus or in the neighborhood of University Heights — as there is in Lincoln Park of Chicago, Illinois (see above). Some might see that as an indicator of the limited effects of the Temperance Movement in the neighborhood of the University of Indianapolis. The founders set out to create a church college in a temperance community, the streets of which were named for temperance-minded bishops of the United Brethren Church. It was a place where parents would want to send their young adult progeny to be educated and where the latter would have the opportunity to develop healthy habits of manliness and womanliness. And of course, they could sign the pledge to abstain – as Irby J. Good ‘08 did.

In MM #68, I present some perspectives of the ICU student experience that I have gathered from the period of Prohibition.

Bibliographical Notes:

The book that I have found to be very useful is Daniel Okrent, Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition (Scribner’s, 2010).

Russell Pulliam’s article “Temperance and Prohibition” in the Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, pp.1326-28) provides a helpful overview of the struggle to establish prohibition in Indianapolis and Marion County.

Jason S. Lantzer, “Prohibition is Here to Stay”: The Reverend Edward S. Shumaker and the Dry Crusade in America (Univ. Notre Dame, 2009)

The Crusade; its Origin and Development at Washington Court House and its Results by Mrs. Matilda Gilruth Carpenter (W. G. Hubbard & Co., 1893)

Elizabeth Putnam Gordon, Women Torch-Bearers: The Story of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (Evanston, IL: National Women’s Christian Temperance Union, 1924)